It’s 1943 and you are making a late evening flight over Southern Sicily.

At 5000 feet your engine starts to splutter and your aircraft begins losing altitude. You panic as alternating black and white smoke pours out of the engine.

At 1000 feet you look at the bumpy ground below and decide it is too rough for a landing. You eject yourself and freefall briefly before pulling the ripcord. You feel a sudden jerk as your parachute opens.

Your chest floods with relief as you float down to land on solid ground – the parachute has just saved your life.

'Life depends on a silken thread'

During the Second World War, near-misses like this were a constant possibility for members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).

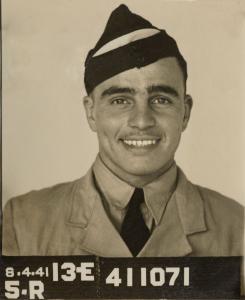

The incident above happened to Sergeant Alexander MacDonald of Waitara in New South Wales. MacDonald would become the second Australian member of an informal yet elite organisation – the Caterpillar Club.

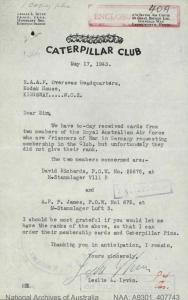

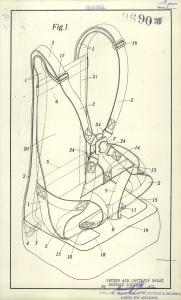

Founded by Californian stuntman Leslie Irvin of the Irvin Air Chute Company in 1922, the Caterpillar Club was open to people who had bailed out of an incapacitated aircraft and been saved by an Irvin parachute.

The club took the motto 'Life depends on a silken thread’ and adopted a caterpillar as their mascot – a reference to the silk threads used to make the earliest parachute. Eligible members would receive a gold caterpillar pin and membership card from the Irvin Air Chute Company

Inspired by the Caterpillar Club, other companies formed similar organisations. Fellow parachute manufacturers Switlik created their own Caterpillar Club, while PB Cow & Co established the Goldfish Club for airmen saved by the firm's life jackets and rubber dinghies.

Behind enemy lines

Sergeant MacDonald was lucky he landed in Allied territory. He was met by concerned villagers and a dying donkey who had been struck by the fallen aircraft. After being fed spaghetti, eggs and bread, MacDonald was given directions to the nearest Allied camp.

Those who crashed behind enemy lines had very different experiences.

On 10 August 1942, after successfully carrying out a bombing mission over Germany, South Australian David Richards was ordered to bail out at 2500 feet.

Once on the ground Richards walked for several hours, eventually taking shelter in an empty barn to dry his soaking uniform. Here he was ambushed by a German civilian brandishing a shotgun, who turned him over to the local mayor. Richards remained a prisoner of war until the end of the war.

Also in August 1942, Victorian Leslie Harvey crashed in Oldebroek, Holland, where a Dutch family handed him over to German authorities.

In his file, Harvey recalls the harsh conditions experienced while imprisoned. He reports on the murder of at least 50 Allied servicemen who tried to escape in March 1944. Their attempt became the subject of the 1963 film The Great Escape.

Harvey also describes a march between POW camps, during which the prisoners were given insufficient food, exposed to freezing conditions (causing many to faint from exposure) and forced to sleep, eat and defecate in the same overcrowded spaces.

A worldwide army of caterpillars

Although they often led to airmen being captured, the Irvin Air Chute Company's parachutes are believed to have saved more than 100,000 lives during the Second World War. By the end of the conflict, over 34,000 Caterpillar Club memberships had been distributed to servicemen of many nations.

Records held by the National Archives show that applications for membership were usually made by senior RAAF officers on behalf of imprisoned airmen, although in some cases the airmen themselves would apply.

While the Caterpillar Club was largely informal, members would wear their pins with pride, a testament to their wartime service and brush with death.