Thanks to a dedicated group of family historians and volunteers, you can now access information about Victoria’s non-European residents during the White Australia policy – without leaving home.

A legacy of White Australia

The infamous dictation test was a key pillar of the White Australia policy and was used primarily to prevent ‘coloured’ (non-European) people from entering Australia. The test could be administered in any European language.

Existing non-European residents travelling overseas could apply for a ‘Certificate Exempting From Dictation Test’ (CEDT) so they did not have to sit the test when returning to Australia.

The Victorian CEDT Register Index unlocks information about thousands of Chinese, Indian, Japanese and other non-European residents of Victoria who applied for CEDTs between 1904 and 1959.

The information comes from original leather-bound registers listing Victorian CEDT applicants held by the National Archives.

A bit of competition goes a long way

Members of the Chinese Australian Family Historians of Victoria used digital cameras to photograph the original registers at the National Archives’ Victoria Office.

They then launched a crowdsourcing appeal for volunteers to help transcribe the more than 13,000 handwritten entries from the registers.

More than 50 volunteers helped with the transcription work. Some was done at the Chinese Museum in Melbourne, with the rest completed online by volunteers from as far afield as Western Australia and Tasmania.

There was stiff competition among the transcribers to see who could complete the most entries.

All up, it took just 3 weeks to transcribe all the entries – instead of the original estimate of 30 weeks.

Searching the index

You can search the index by name, age, nationality, residence, occupation and year.

The index links to digital images of the original registers, and in some cases, back to the corresponding Collector of Customs correspondence file held by the National Archives.

Teddy’s story

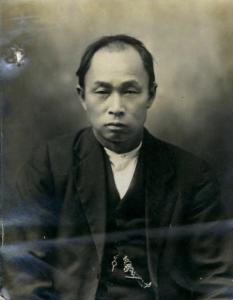

The index will help you to discover the individual stories behind the names recorded in the registers – such as that of Edward ‘Teddy’ Chung Ah Gan, who was granted a CEDT in 1917.

Teddy was a fruit-seller and market gardener from Brighton, a bayside suburb of Melbourne. He was a naturalised British subject and was married to an Australian woman, Annie Harris.

In 1917, Teddy took Annie and their children, George, Frederick, Dorothy and Ruby, back to China. Before leaving Melbourne, he obtained CEDTs for himself and for the children. To get these, Teddy supplied the required photographs and character references, which were checked by the police.

Although these assessments were favourable, they reflected the racial prejudices of the era: one specifically commended Teddy’s family for their ‘cleanliness’. Teddy and his children were also fingerprinted as part of the process.

The family’s CEDTs permitted them to return to Australia within 3 years without having to take the dictation test.

By the time Teddy decided to return to Australia, however, his CEDT had long expired. Teddy sought to re-enter on the basis that he had been naturalised in Australia, but his application was denied. The minister decided that, given how long Teddy had been away, he was ‘unable to see his way to grant authority for his re-admission’. The minister also stated that Teddy’s naturalisation ‘was only effective locally’. He was therefore not entitled to a passport to re-enter Australia except by an ‘act of grace’, which the minister was not prepared to make.

What happened to Teddy, his wife and 4 children? Did any of them ever return to Australia?

On this, sadly, the registers are silent.