An air of unreality

Sunday 5th January, 1975 9:27 pm

Sunday the 5th of January 2025 marks 50 years since the tragic event that took the lives of 12 people and severed the connection between Hobart and its eastern shore suburbs.

A description of the incident quoted from a report in the Hobart Mercury the following morning read:

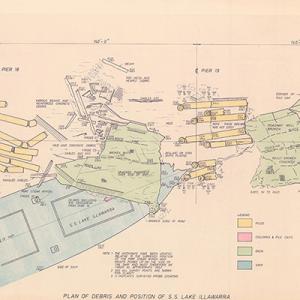

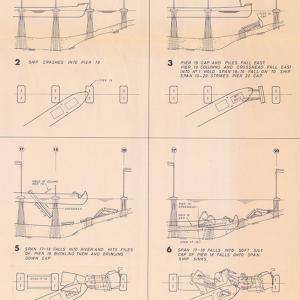

More than 10 people died last night when a 10,000-ton ship, the Lake Illawarra, knocked a section out of the Tasman Bridge and sank in more than 80 feet of water in about 10 minutes.

With the bow already submerged under the weight of the collapsed bridge span the Lake Illawarra’s stern pointed skyward, seconds later it had sunk in a cloud of spray.

Few could fully comprehend the meaning of the disaster, the lives lost, the destruction of both the Lake Illawarra and the Bridge itself and the huge traffic problems which will face Hobart residents for months, perhaps years to come.

There was an air of unreality about the disaster.

At the time this was a unique event – never had a city been suddenly separated in 2 halves. Authorities had dealt with natural calamities and disasters in the past, but this short sharp impact had different repercussions.

For the community it was obvious that their lives would be seriously disrupted. The depth of this disturbance though extended beyond the cost of repairing a broken bridge and a sunken ship.