Few construction projects equal the scale of Parliament House, which opened in May 1988 after a 7-year building program. Yet there were 5 significantly different visions for this iconic structure, each captured by a massive flying-saucer like model held in the National Archives’ collection.

Announced by Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser on 7 April 1979, the Parliament House Design Competition sought to honour Walter Burley Griffin’s original plan for Canberra.

Although the site on Capital Hill had been agreed by Parliament in 1974, the scope of the brief was enormous. Its 20 volumes required architects to consider not only light, acoustics and furnishings, but catering, security and broadcasting facilities. A key tension underlying the contest was balancing the political urge to erect a monumental structure against respecting the capital’s natural landscape.

The judging committee boasted leading local and international architects, an engineer and 2 members of Parliament. The competition’s first stage attracted 328 submissions spanning all of the Australian states, although not the Northern Territory. Local firms were pitted against overseas entrants from 19 nations as diverse as Pakistan, Poland, Brazil, Israel, Mexico, Hong Kong, South Korea, South Africa, the Netherlands and New Zealand.

Placing politics within the land

Coinciding with an emerging shift in architectural practice from modernist to postmodern forms, many proposals remained faithful to the geometric principles enshrined in Griffin’s 1912 scheme. Other designs, however, took a more organic and playful approach to how the building might relate to the city’s administrative and residential nodes emanating from Capital Hill.

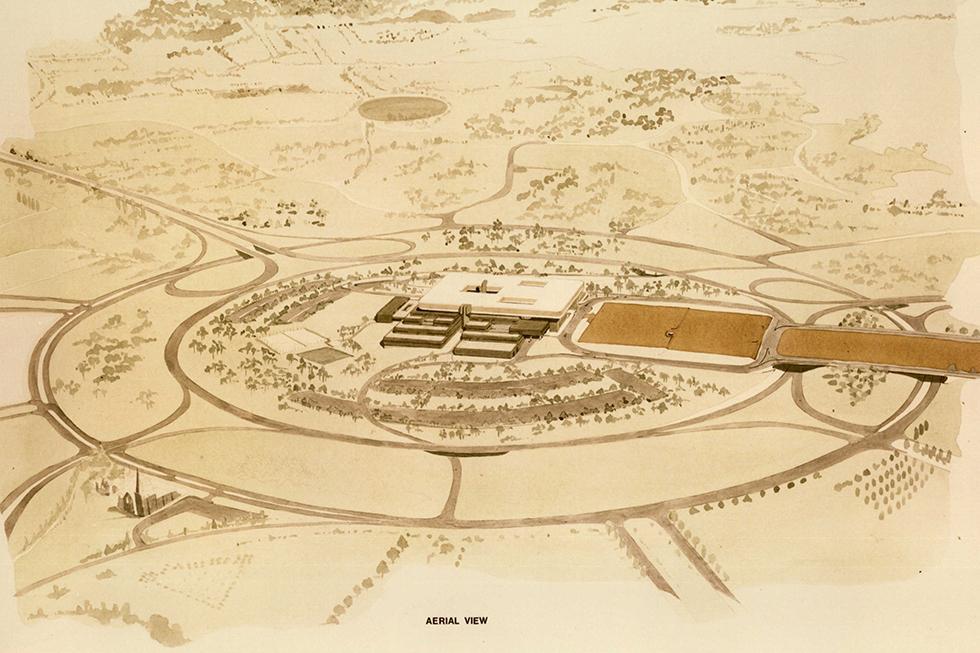

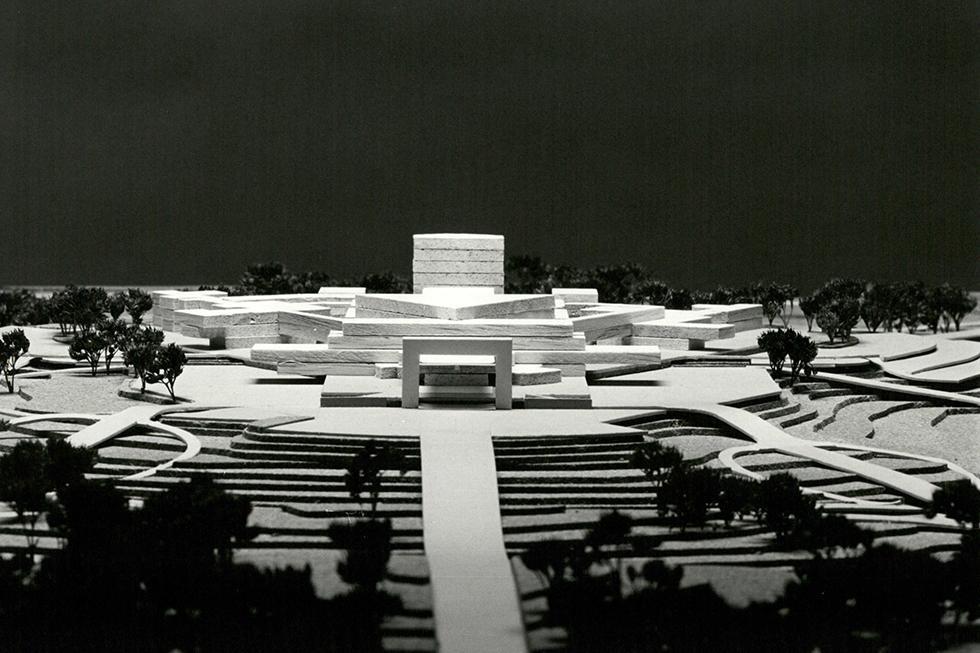

Handed down in June 1980, the assessors’ report selected 5 entries to go forward to the second stage. Each finalist was required to submit a large circular model to illustrate both the building itself and how it related to the local landform. Constructed to a scale of 1:200, and measuring approximately 1.5 metres in diameter, these vignettes varied enormously in how they interpreted Australia’s seat of representative democracy.

Two Australian entries, by Denton Corker Marshall and Edwards Madigan Torzillo, projected largely linear structures that sat firmly above the landscape.

Conversely, the British firm of Bickerdike Allen Partners and Canadian architects Parsons and Waite both imagined low-lying buildings that emerged from the hill.

The diversity of these proposals drives home the singular vision of the American-led winning submission by Mitchell, Giurgola and Thorp. Even today, the fidelity of Parliament House to their final 1983 model bears testament to the architects’ deeply considered approach to space, light, form and flow. While their signature 4-piered flagstaff gestured to Griffin’s unrealised design for a Capitol building, the new Parliament House embedded both the place and process of politics within the land itself.