Gwalia was a town of migrants. When the Western Australian gold rush began in the 1890s, large numbers of people from Australia and around the world made their way to the state’s remote goldfields and towns like Gwalia in search of economic opportunity.

Italians and Yugoslavs were prominent among these new arrivals. Some left their countries of birth because of economic and environmental factors, such as crop devastation. Some young men emigrated to escape conscription into the Austro-Hungarian military as tensions escalated in the Balkans. Others may have simply decided that opportunities to earn a living were greater on the booming goldfields than at home.

Dangerous and difficult work

According to the secretary of the Department of Immigration, these migrants filled many of the jobs that Anglo-Australians were 'loathe to accept'. Yugoslav and Italian labourers often performed dangerous and unpleasant underground work.

Southern European migrants also joined the timber industry. Woodlines supplied timber for the construction of supports in underground shafts and use as a fuel source. Working as a wood cutter avoided the risks of disease due to inhaled mining dust, but cutting wood carried its own dangers. Isolated locations meant that medical help was often hours away.

Despite being willing to do jobs that Anglo-Australian workers refused, European migrants faced fierce resistance from trade unions. These advocated for the regulation of the entry and employment of non-British workers. The union movement showed a preference for migrant workers to be employed outside of major towns, where facilities such as schools were available. Similarly, the language test for underground mine work introduced in 1906 was generally applied more strictly in larger mines closer to major towns to exclude non-British workers. During the Depression, the union movement was even more insistent that migrants should not be employed if British subjects willing to work were available.

Meet some Gwalia residents

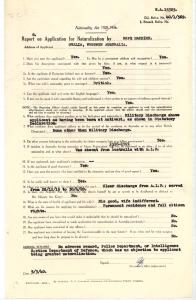

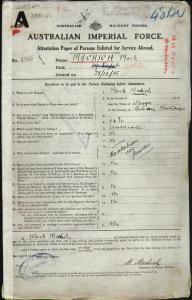

Mark Machich emigrated from Montenegro and arrived in Fremantle in 1911, before making his way to the goldfields and settling in Gwalia. When war broke out he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and served from 1915 to 1920. Had he stayed in Montenegro he may have fought against Australian soldiers. After the war he returned to work in the goldfields. He became an Australian citizen in 1940, and joined the Volunteer Defence Corps in 1942 at the age of 52.

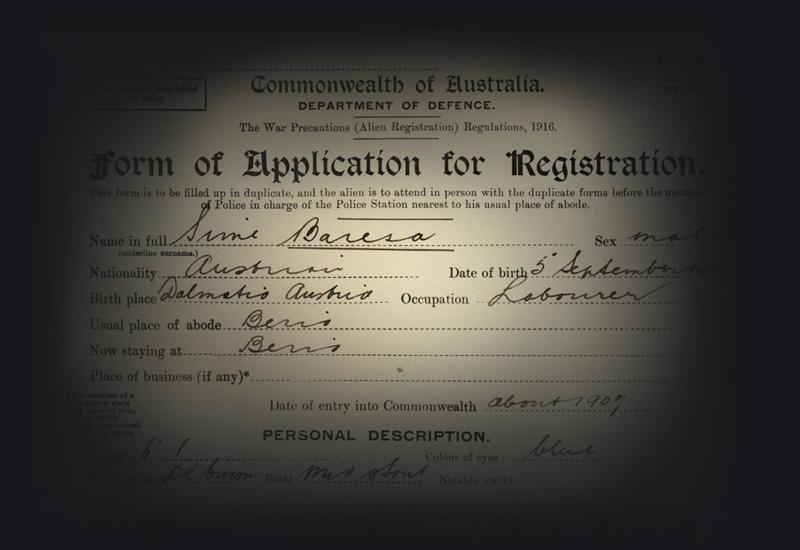

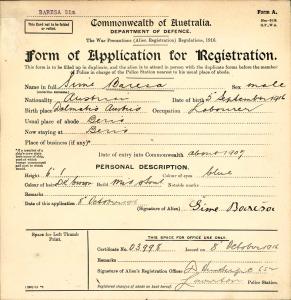

Sime Baresa, an Austrian national born in Vodice, Dalmatia, entered Australia in 1907 at age 23. He also found work as a miner. During World War 1 he was required to register as an alien and report any changes of address to authorities. His alien registration documents show that Baresa spent time in Beria and Menzies as well as Gwalia – all of which later became ghost towns. After more than a decade of working in the goldfields, Baresa became an Australian citizen in 1921.

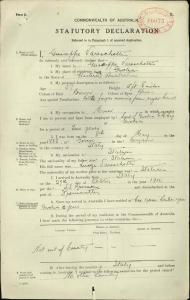

One of Gwalia's long-standing residents was Giuseppe Varischetti. He arrived from Italy in 1910 and was part of the earliest cohort of Italian miners to come to the Western Australian goldfields. During his life in Gwalia, he had 5 children, 2 of whom served in the Australian defence forces during World War II. In 1941, at the age of 51, Varischetti died with his cause of death given as Miner’s Lung. This was no doubt caused by years of hard work underground in the Sons of Gwalia goldmine.