The Colombo Plan

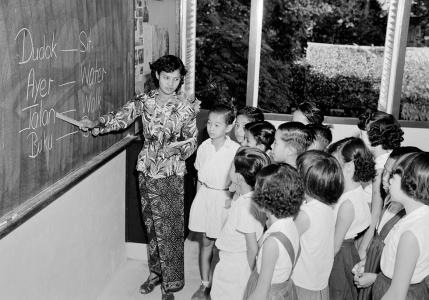

In the 1950s and 1960s another group of Malays were treated very differently, often invited into the lives and homes of ordinary Australians. Under a cooperative development scheme known as the Colombo Plan, thousands of students from Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan and India [Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines and Japan] came to Australia to attend local tertiary institutions.

Under the Colombo Plan, Australia provided economic and technical assistance to South and South-East Asian countries. By contributing to social and economic development, it was hoped to maintain security and stability within the region, steering Australia's neighbours clear of communism. Australian policy-makers also expected that the positive relationships established under the scheme would help defuse criticism in Asia of the White Australia Policy.

Changing perceptions

The Colombo Plan certainly changed perceptions in Australia, where the presence of the friendly young Asian students contributed to the thawing of old, entrenched prejudices. The majority of the students were Muslims from middle-class families. Intelligent and usually proficient in English, they were quickly accepted by their Australian hosts. Friendships were forged as many Anglo-Celtic homes welcomed the newcomers.

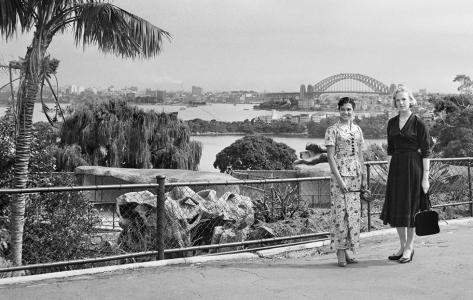

The 2000th Colombo Plan student

The selection and arrival of the 2000th Colombo Plan student, an 'attractive Malayan girl', was the subject of extensive publicity both in Australia and Asia. Twenty-one-year-old Ummi Kelsom was an ideal ambassador for the scheme. The fifth child of an upper-middle class family, she spoke English fluently, and was both a badminton champion and a keen girl guide. She had even prepared for her visit to Australia by learning how to drive a Holden.