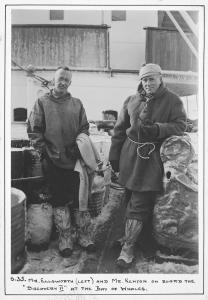

On 23 November 1935, American Lincoln Ellsworth flew across the Antarctic to explore and map new territory. But when arduous conditions and insufficient fuel forced his plane to land, he and his pilot were stranded on a remote base with no way to contact the outside world. The Australian government, with help from the British, launched a rescue expedition that captured the attention of the world.

A polar explorer

Lincoln Ellsworth, born in Chicago in 1880, was the son of a successful coal magnate. He developed an interest in polar exploration, joining Roald Amundsen's attempted flight to the North Pole in 1925, as well as his successful 1926 attempt in an airship. Ellsworth later turned his attention to the southern hemisphere, making a total of 4 expeditions to the Antarctic between 1933 and 1939.

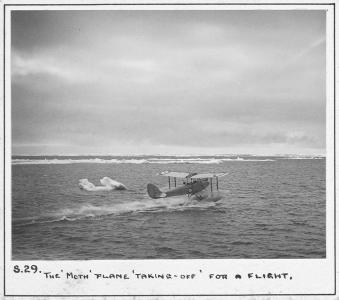

In the 1930s, much of Antarctica remained unmapped. Ellsworth believed using aircraft was the best way to chart such a vast expanse of territory. In November 1935, Ellsworth and pilot Herbert Hollick-Kenyon flew a Northrop Gamma aircraft named Polar Star across Antarctica.

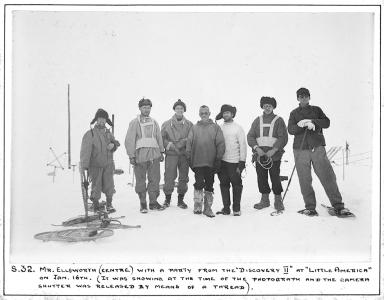

During the expedition, Ellsworth and Hollick-Kenyon made a 14-hour flight, but damaged their fuselage and broke their radio when landing. They tried to resume their flight but were forced to wait out a blizzard for 8 days. After digging their plane out with just a teacup, they managed to get back in the air – but by then they had run out of fuel. They were forced to land again, and hike for 11 days to the exploratory base of Little America. There, they could do little but wait and hope for rescue.