If I could only get this abomination sunk by Federal authority before I leave this country or after, I will not have lived in vain.

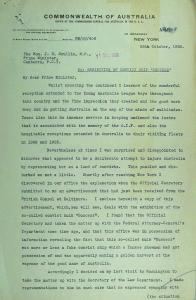

Thus wrote Australia’s commissioner-general in the United States, Herbert Brookes, to acting prime minister JE Fenton on 17 October 1930. The ‘abomination’ referred to was an antique wooden barque called the Success, and its perceived crime was to present to the world a slanderous image of Australia as a nation built on convictism and cruelty.

From Indian trader to touring horror show

Since its construction in the shipyards of Burma (now Myanmar) in 1840, the Success had served as an Indian trader, immigrant ship, prison hulk, reformatory for boys and explosives tender.

From 1895 it became an international cultural exhibit. Used to tout a nightmarish vision of Australia’s past to the rest of the world, it carried a cargo of wax bushrangers and convicts, flogging frames, branding irons and other implements of torture. It was this unflattering historical interpretation that Brookes and previous commissioners strenuously sought to remove from the public gaze.

The history of the Success exhibition presents a striking example of the evolution of Australia’s self-image. Its service as a floating prison for the Victorian colonial government between 1853 and 1859 provided the original inspiration for the Melbourne showmen who purchased it in 1890. The enterprising entertainers were keen to exploit the Australian public’s appetite for a gothic convict narrative fostered by the novel For the term of his natural life and other similar depictions.

Misrepresented as an original convict transport, the ship and its grisly show toured the Australian colonies between 1891 and 1895. It drew healthy visitor numbers before being taken to England and, in 1912, the United States. The exhibition remained true to its original conception throughout, while in its wake Australia’s sense of national identity continued to evolve in response to Federation and the Anzac legend.

Agents and archives

To support the efforts of one of Brookes’s predecessors, James Elder, to debunk the ship’s fabricated background, the Commonwealth’s principal intelligence agency had entered the fray. The commissioner’s queries were referred to the Investigation Branch of the Attorney-General’s Department. It embarked on ‘quite an interesting incursion into the fields of historical research’, in the words of one inspector.

The investigation was wide ranging, and agents more at home monitoring political meetings were to be found poring over archival records in Sydney and Melbourne. Director HE Jones’s resulting report of July 1926, preserved in the National Archives’ files concerning the Success, incorporates a history of the ship based on these sources.

The report conclusively demonstrated that most of the more sensational elements in the promotional literature were false. In Jones’s view, they were ‘beyond any exaggeration which may be conceded as the license of a showman’.

A belated sinking

There was, however, little capital gained from these investigative efforts. This was partly because commissioners and the Australian Government alike feared that publicised attacks on the exhibition could merely play into the hands of its showman promoters.

For his part, Brookes worked assiduously to have the exhibition shut down through approaches to influential United States officials. These included the then governor of the State of New York – a former secretary for the navy and collector of models of historic ships – Franklin Roosevelt. The governor promised to raise the matter with the federal authorities.

The life-affirming sinking Brookes wrote of would not, however, occur until much later in 1946, and through a common act of vandalism. By then the Success was largely forgotten in both Australia and the United States. The burning of the grounded, half-stripped hulk in Lake Erie, near Port Clinton, Ohio, drew little comment beyond the local newspapers.