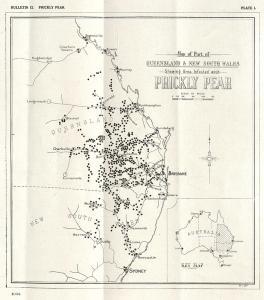

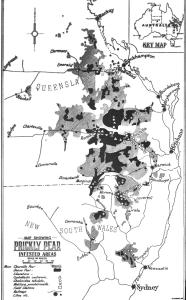

The spread of prickly pear is like the invasion of a dangerous enemy, advancing slowly but steadily and gradually taking possession of our continent.

Rabbits, pigs, blackberries … Australia has a troubled history of introduced species wreaking havoc in its unique environment.

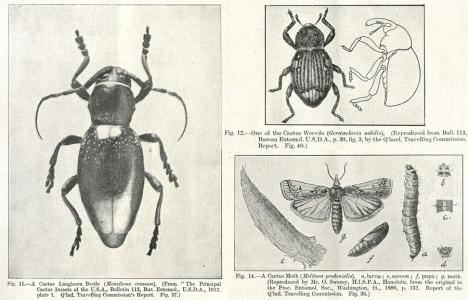

The prickly pear was one such species. Introduced in the early days of the colony, by the 1900s it had taken over large tracts of land in Australia's eastern states.

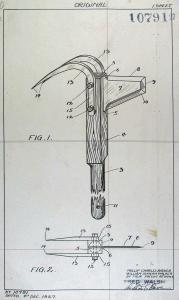

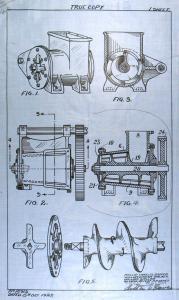

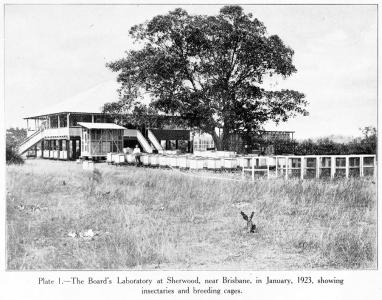

Attempts to stop the thorny pest were nothing less than full-scale war – as records in the National Archives reveal.