War expanded their horizons; war provided new opportunities; war sent them to work. And men sent them home again.

Come on, housewife. Take a Victory job

Throughout the Second World War, many men volunteered to fight, which meant their jobs were left empty. Often the only people to fill those jobs were women. Areas of work which desperately needed the help of women included traditionally male roles in factories and shipyards, and on farms.

But first the government had to inspire women to work outside the home, something not many women did. It was a deeply ingrained social expectation at the time that women would look after children and the home, and that men would work.

Propaganda was the answer, and the government launched a vibrant propaganda campaign to encourage women to step out of the home and into new roles supporting the war effort.

Propaganda covered all angles and was aimed at a wide range of audiences: from bored housewives looking for fun to fashion-forward city girls seeking a 'change of scene'. Some employed shock tactics to jolt mothers into action, urging them to: 'help … save some mother's baby' from being 'bayoneted, burnt or bombed'. Women with little or no experience of working outside the home were encouraged to 'have a heart-to-heart talk with another woman' at their nearest National Service Office.

Factories and farms

The campaign worked. Between 1939 and 1943, women's participation in the workforce increased by a third.

Women who joined the Australian Women’s Army Service undertook civilian military duties such as signalling, driving and intelligence gathering, thereby freeing up men to join fighting units.

Another key organisation was the Australian Women’s Land Army (AWLA). It was created in an attempt to address labour and food shortages as a result of large numbers of male farmers joining the armed forces. Common jobs included growing fruit and vegetables, shearing sheep, ploughing fields, milking cows and raising animals.

Women unable to take positions outside the home contributed to the war effort by using their spare time to knit. The government and various war-related organisations introduced specific knitting patterns and guidelines about what could be knitted.

'Placid little woman'

The Second World War brought about drastic changes in women’s lives. They went from focusing on the home to serving on the home front. Some even became the main breadwinner for their families.

Even before the war was over, women were wondering what their postwar futures would hold. They knew that once men returned to the workforce, jobs would be hard to come by. One wrote to Sydney newspaper Smith's Weekly that she 'did not want to ‘revert to the placid little woman she was prior to enlistment'. Rather, she wanted to 'retain that feeling of equality … that Army had given her; and had no desire to become the chattel or slave of a basic wage-earning male – to have babies and live in semi-poverty'.

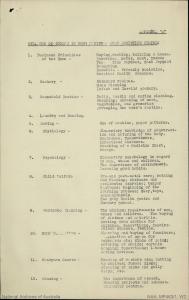

Yet it was not a sentiment shared by all. Major-General Stantke worriedly wrote that 'the longer the war lasts, the less inclined will such female personnel be … to take up home duties upon the efficiency of which the future of the nation is largely dependent'. 'There is, therefore,' he declared, 'A necessity to commence … a type of education which will divert them from the rut into which many have slipped', proposing that courses be offered in 'Dressmaking, Cookery, and Home Management'. Domestic science training was to become the cornerstone of the government's post-Armistice 'rehabilitation' of Australia’s service women.

Having pulled out all the stops to entice women out of the kitchen, the government, it seemed, was now hell-bent on sending them back in.