Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that the National Archives' website and collection contain the names, images and voices of people who have died.

Some records include terms and views that are not appropriate today. They reflect the period in which they were created and are not the views of the National Archives.

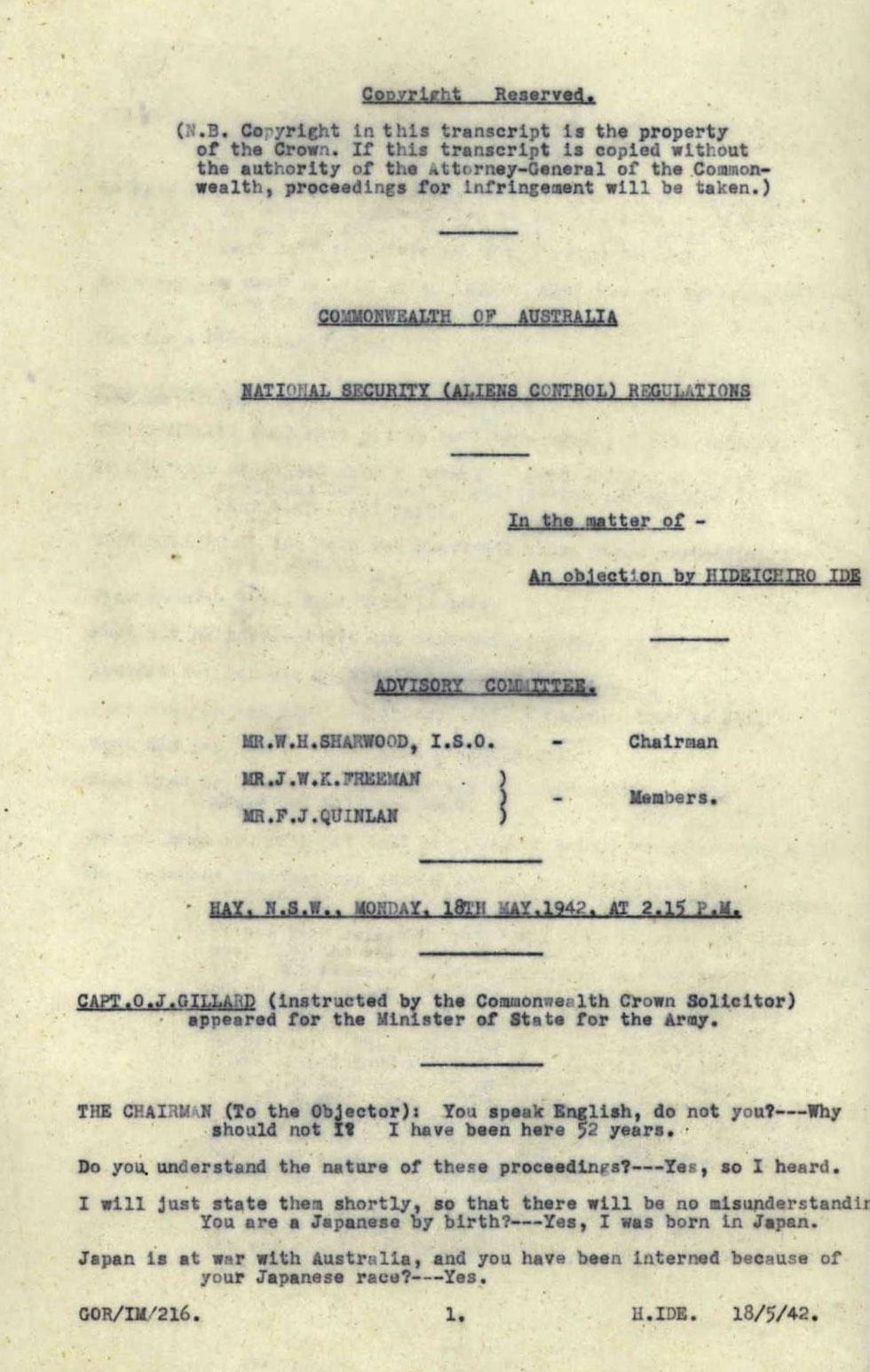

[Page 1.]

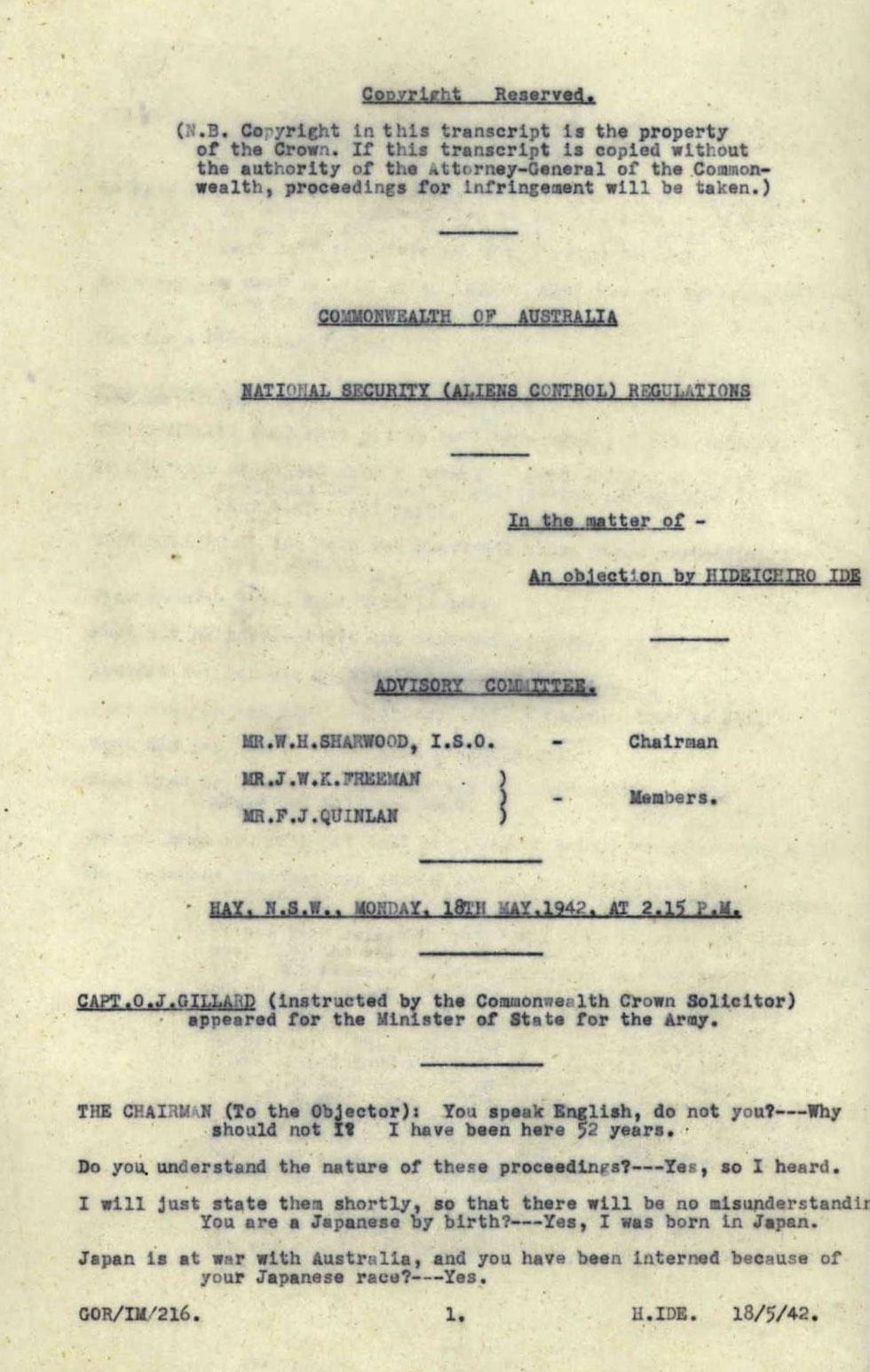

[Underlined] Copyright Reserved.

(N.B. Copyright in this transcript is the property of the Crown. If this transcript is copied without the authority of the Attorney-General of the Commonwealth, proceedings for infringement will be taken)

[Dividing line.]

[Underlined] COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

[Underlined] NATIONAL SECURITY (ALIENS CONTROL) REGULATIONS

[Dividing line.]

[Underlined] In the matter of –

[Underlined] An objection by HIDEICHIRO IDE

[Dividing line.]

[Underlined] ADVISORY COMMITTEE.

MR.W.H.SHARWOOD, [sic] I.S.O. – Chairman

MR.J.W.K.FREEMAN[,] MR.F.J.QUINLAN [sic] – Members.

[Dividing line.]

[Underlined] HAY. N.S.W.. MONDAY. 18TH MAY. 1942. AT 2.15 P.M.

[Dividing line.]

[Underlined] CAPT.O.J.GILLARD[sic] [end underlined.] (instructed by the Commonwealth Crown Solicitor) appeared for the Minister of State for the Army.

[Dividing line.]

THE CHAIRMAN (To the Objector): You speak English, do not you? --- Why should not I? I have been here 52 years.

Do you understand the nature of these proceedings? --- Yes, so I heard.

I will just state them shortly, so that there will be no misunderstandin[g.] You are a Japanese by birth? --- Yes, I was born in Japan.

Japan is at war with Australia, and you have been interned because of your Japanese race? --- Yes.

GOR/IM/216. 1. H.IDE. 18/5/42

[Page 2.]

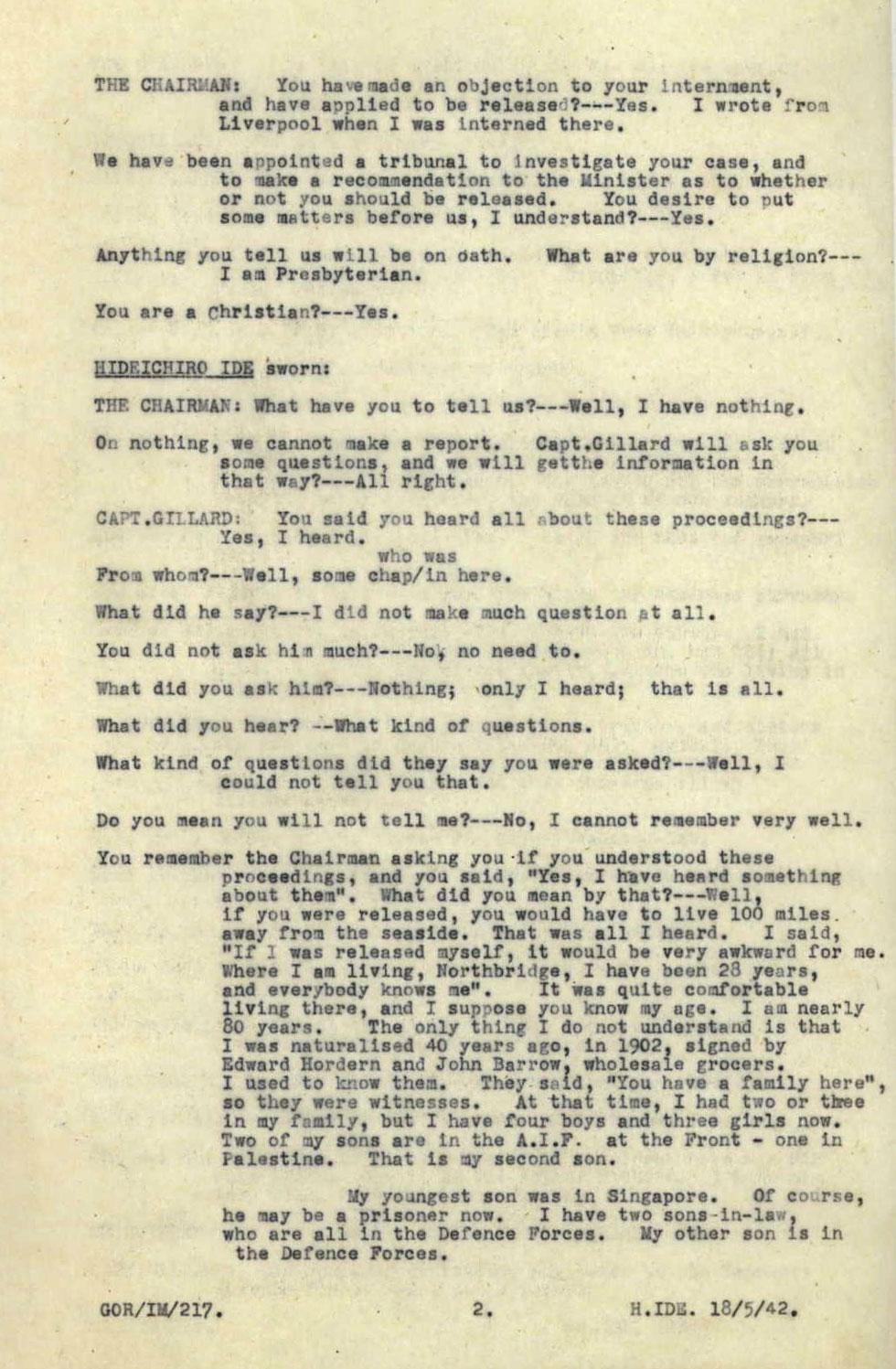

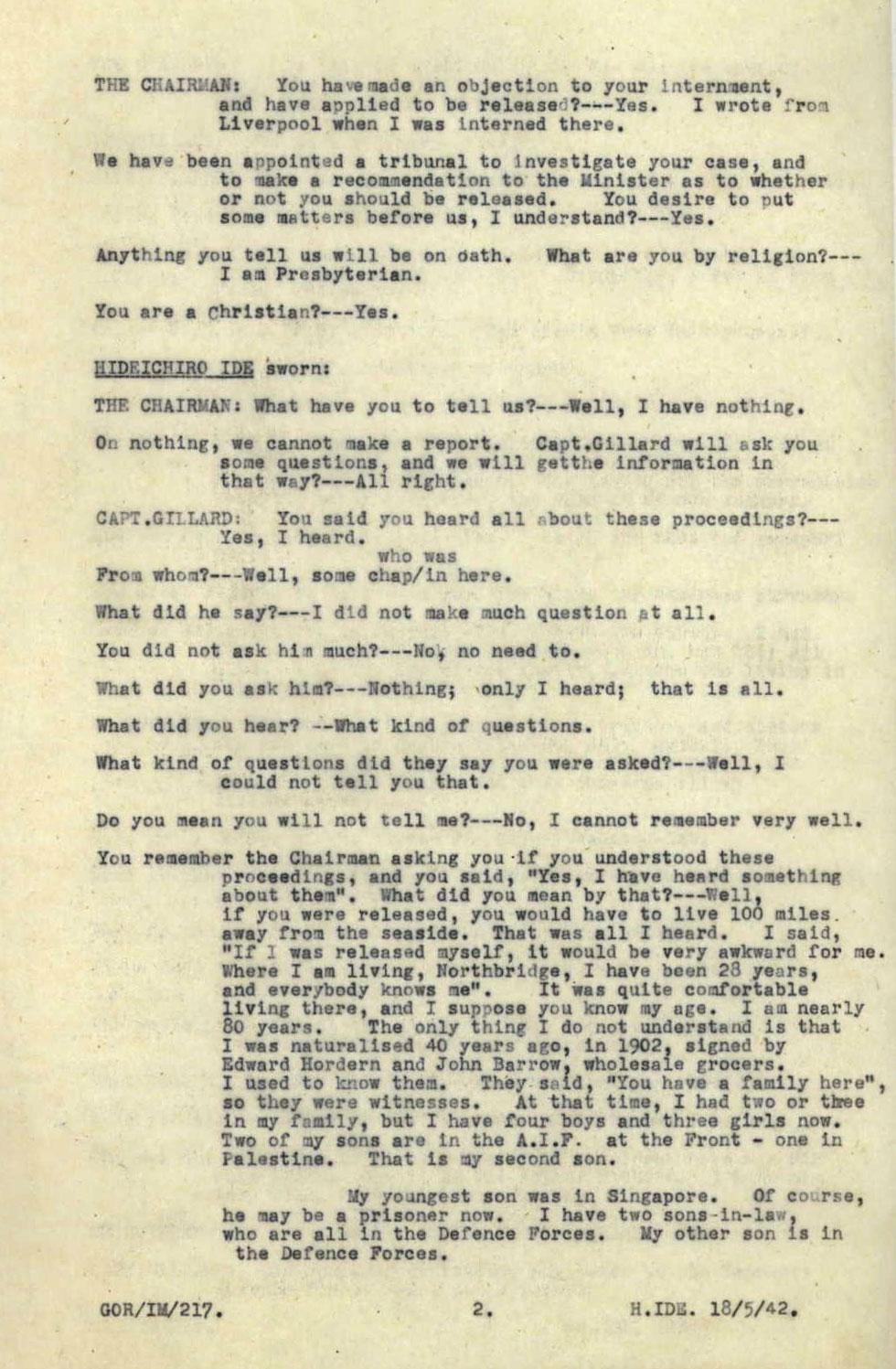

THE CHAIRMAN: You have made an objection to your internment, and have applied to be released? --- Yes. I wrote from Liverpool when I was interned there.

We have been appointed a tribunal to investigate your case, and to make a recommendation to the Minister as to whether or not you should be released. You desire to put some matters before us, I understand? --- Yes.

Anything you tell us will be on oath. What are you by religion? --- I am Presbyterian.

You are Christian? --- Yes.

[Underlined] HIDEICHIRO IDE [end underlined] sworn:

THE CHAIRMAN: What have you to tell us? --- Well, I have nothing.

On nothing, we cannot make a report. Capt.Gillard[sic] will ask you some questions, and we will getthe [sic] information in that way? --- All right.

CAPT.GILLARD [sic]: You said you heard all about these proceedings? --- Yes, I heard.

From whom? --- Well, some chap [inserted text reads: /who was] in here.

What did he say? --- I did not make much question at all.

You did not ask him much? --- No, no need to.

What did you ask him? --- Nothing; only I heard; that is all.

What did you hear? --- What kind of questions.

What kind of questions did they say you were asked? --- Well, I could not tell you that.

Do you mean you will not tell me? --- No, I cannot remember very well.

You remember the Chairman asking you if you understood these proceedings, and you said, “Yes, I have heard something about them”. What did you mean by that? --- Well, if you were released, you would have to live 100 miles away from the seaside. That was all I heard. I said, “If I was released myself, it would be very awkward for me. Where I am living, Northbridge, I have been 28 years, and everybody knows me”. It was quite comfortable living there, and I suppose you know my age. I am nearly 80 years. The only thing I do not understand is that I was naturalised 40 years ago, in 1902, signed by Edward Hordern and John Barrow, wholesale grocers. I used to know them. They said, “You have a family here”, so they were witnesses. At that time, I had two or three in my family, but I have four boys and three girls now. Two of my sons are in the A.I.F. at the Front – one in Palestine. That is my second son.

My youngest son was in Singapore. Of course, he may be a prisoner now. I have two sons-in-law, who are all in the Defence Forces. My other son is in the Defence Forces.

GOR/IM/217. 2. H. IDE. 18/5/42

[Page 3. This transcript returns to the trail at page 10 of the record. We enter the line of questioning partway through regarding H. Ide’s time on Cargo boats in the 1930’s.]

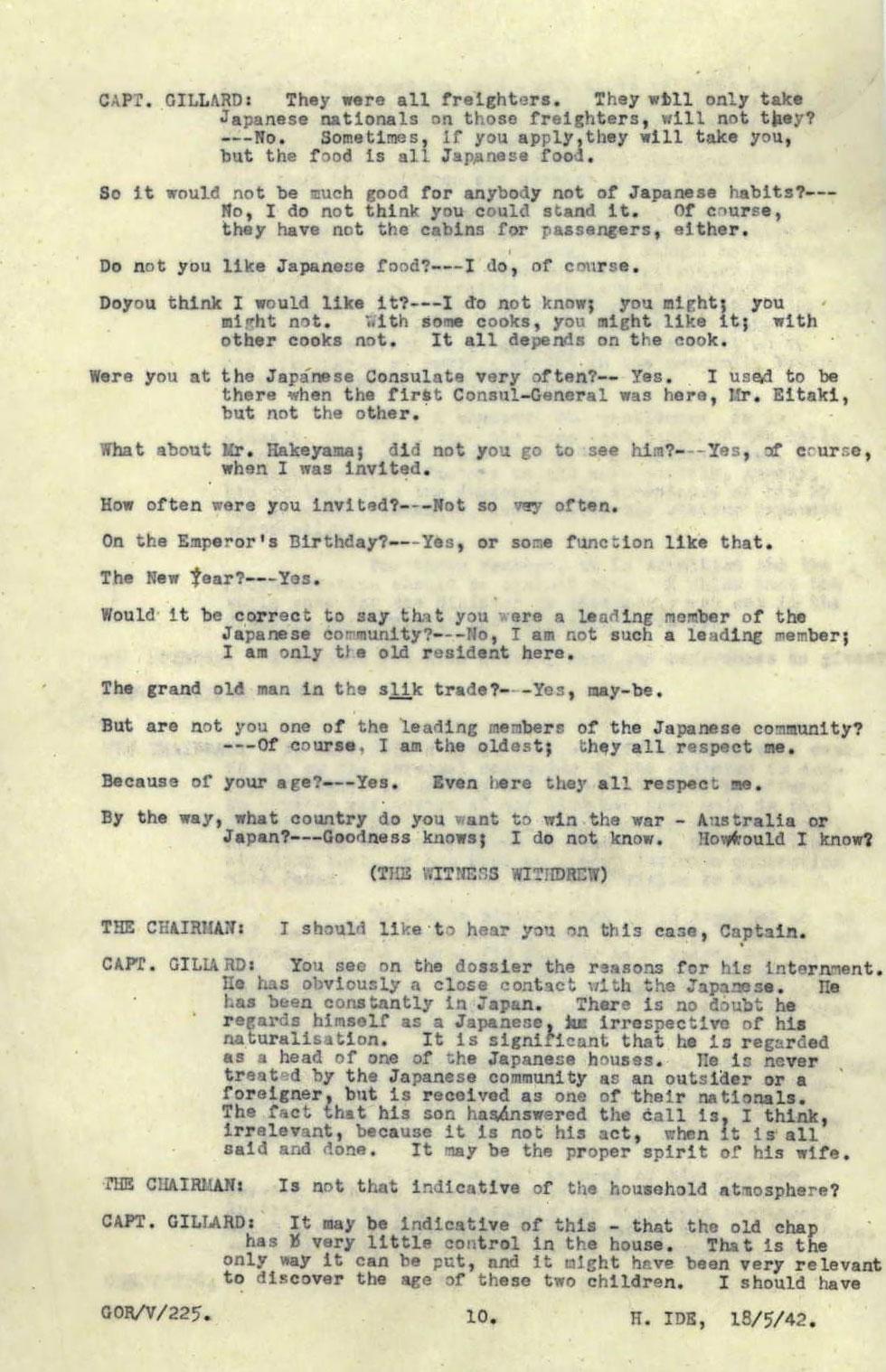

CAPT. GILLARD: They were all freighters. They will only take Japanese nationals on those freighters, will not they? --- No. Sometimes, if you apply, they will take you, but the food is all Japanese food.

So it would not by much good for anybody not of Japanese habits? --- No, I do not think you could stand it. Of course, they have not the cabins for passengers, either.

Do not you like Japanese food? --- I do, of course.

Doyou [sic] think I would like it? --- I do not know; you might; you might not. With some books, you might like it; with other cooks not. It all depends on the cook.

Were you at the Japanese Consulate very often? – Yes. I used to be there when the first Consul-General was here, Mr. Eitaki, but not the other.

What about Mr. Hakeyama/ did not you go to see him? --- Yes, of course, when I was invited.

How often were you invited? --- Not so very often.

On the Emperor’s Birthday? --- Yes, or some function like that.

The New Year? --- Yes.

Would it be correct to say that you were a leading member of the Japanese community? --- No, I am not such a leading member; I am only the old resident here.

The grand old man in the [underlined] silk [end underlined] trade? --- Yes, may-be.

But are not you one of the leading members of the Japanese community? ---- Of course, I am the oldest; they all respect me.

Because of your age? --- Yes. Even here they all respect me.

By the way, what country do you want to win the war – Australia or Japan? --- Goodness knows; I do not know. How/would [sic] I know?

(THE WITNESS WITHDREW)

THE CHAIRMAN: I should like to hear you on this case, Captain.

CAPT. GILLARD: You see on the dossier the reasons for his internment. He has obviously a close contact with the Japanese. He has been constantly in Japan. There is no doubt he regards himself as a Japanese, [crossed out, illegible] irrespective of his naturalisation. It is significant that he is regarded as a head of one of the Japanese houses. He is never treated by the Japanese community as an outsider or a foreigner, but is received as one of their nationals. The fact that his son has/answered [sic] the call is, I think, irrelevant, because it is not his act, when it is all said and done. It may be the proper spirit of his wife.

THE CHAIRMAN: Is not that indicative of this – that the old chap has b[letter crossed out] very little control in the house. That is the only way it can be put, and it might have been very relevant to discover the age of these two children. I should have [...]

GOR/V/225. 10. H. IDE, 18/5/42

[Page 4.]

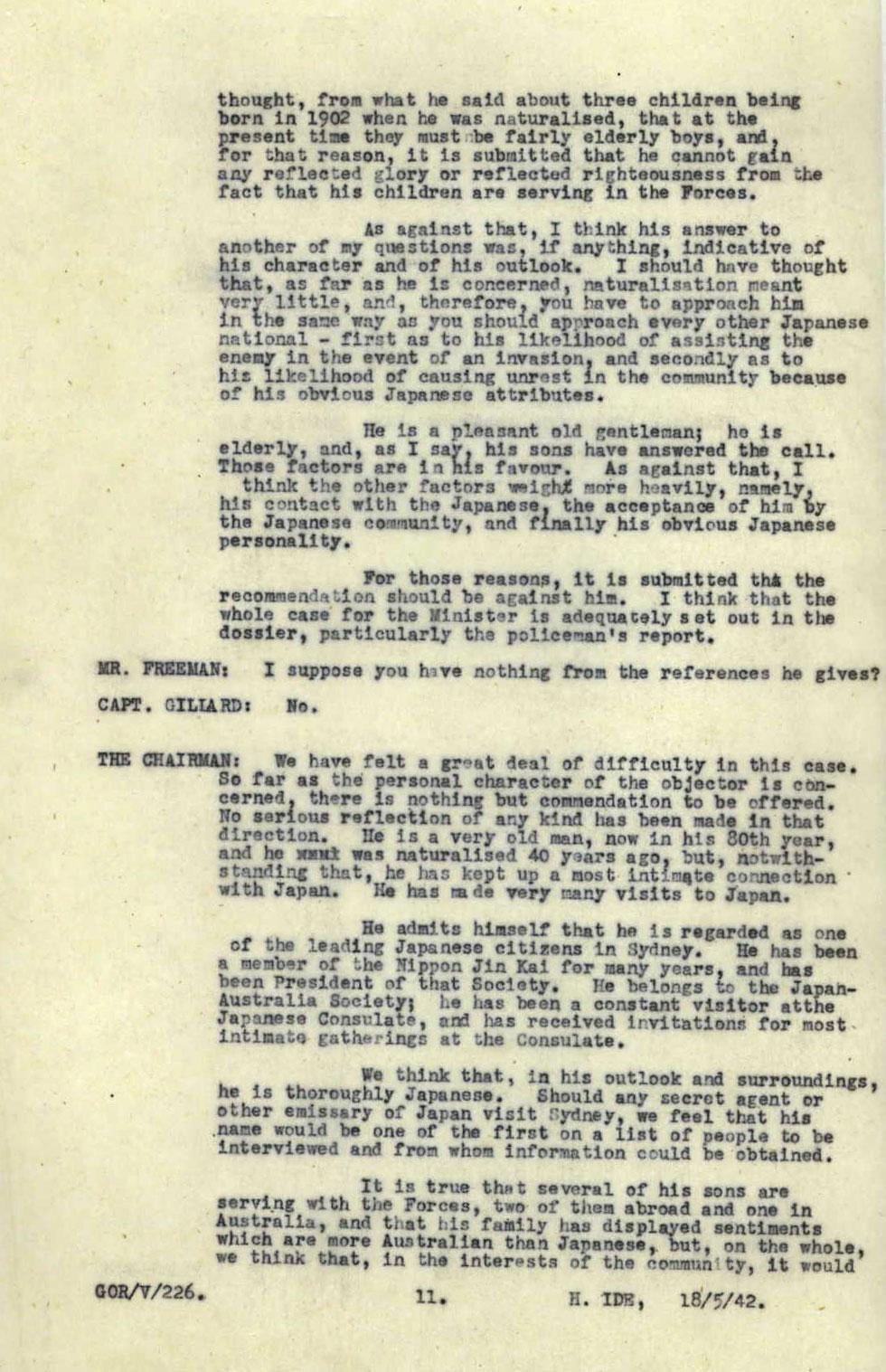

[I should have] thought, from what he said about three children being born in 1902 when he was naturalised, that at the present time they must be fairly elderly boys, and, for that reason, it is submitted that he cannot gain any reflected glory or reflected righteousness from the fact that his children are serving in the Forces.

As against that, I think his answer to another of my questions was, if anything, indicative of his character and of his outlook. I should have thought that, as far as he is concerned, naturalisation meant very little, and, therefore, you have to approach him in the same way as you should approach every other Japanese national – first as to his likelihood of assisting the enemy in the event of an invasion, and secondly as to his likelihood of causing unrest in the community because of his obvious Japanese attributes.

He is a pleasant old gentleman; he is elderly, and, as I say, his sons have answered the call. Those factors are in his favour. As against that, I think the other factors weight [t crossed out so word reads weigh] more heavily, namely, his contact with the Japanese, the acceptance of him by the Japanese community, and finally his obvious Japanese personality.

For those reasons, it is submitted th [crossed out] the recommendation should be against him. I think that the whole case for the Minister is adequately set out in the dossier, particularly the policeman’s report.

MR FREEMAN: I suppose you have nothing from the references he gives?

CAPT. GILLARD: No.

THE CHAIRMAN: We have felt a great deal of difficulty in this case. So far as the personal character of the objector is concerned, there is nothing but commendation to be offered. No serious reflection of any kind has been made in that direction. He is a very old man, now in his 80th year, and he xxx [word crossed out] was naturalised 40 years ago, but, notwithstanding that, he has kept up a most intimate connection with Japan. He has made very many visits to Japan.

He admits himself that he is regarded as one of the leading Japanese citizens in Sydney. He has been a member of the Nippon Jin Kai for many years, and has been President of that Society. He belongs to the Japanese Australia Society; he has been a constant visitor atthe [sic] Japanese Consulate, and has received invitations for most intimate gatherings at the Consulate.

We think that, in his outlook and surroundings, he is thoroughly Japanese. Should any secret agent or other emissary of Japan visit Sydney, we feel that his name would be one of the first on a list of people to be interviewed and from whom information could be obtained.

It is true that several of his sons are serving with the Forces, two of them abroad and one in Australia, and that his family has displayed sentiments which are more Australian than Japanese, but, on the whole, we think that, in the interests of the community, it would […]

GOR/V/226. 11. H. IDE, 18/5/42.

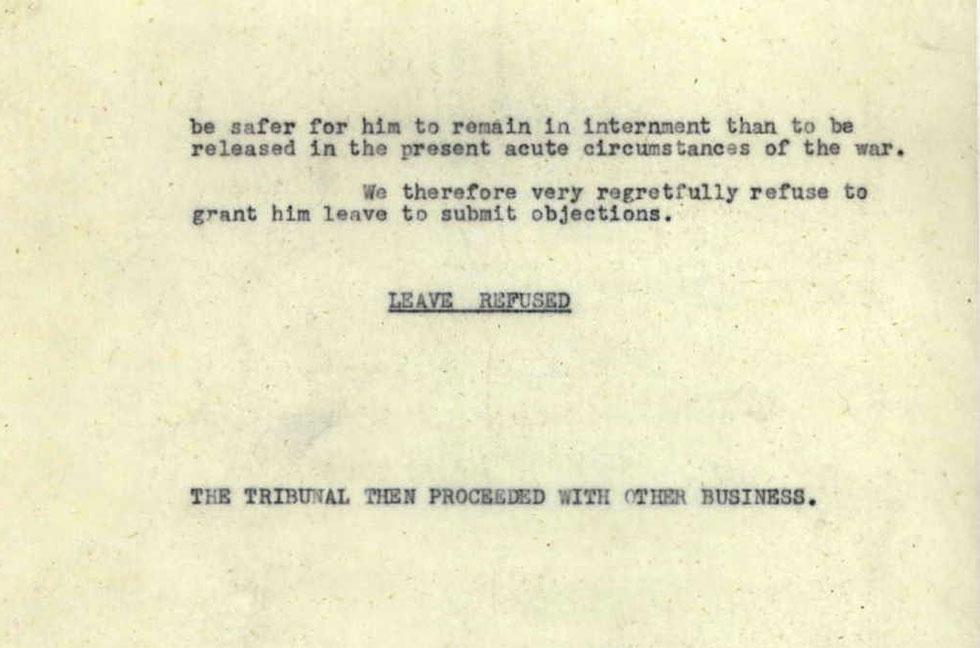

[Page 5.]

[… it would] be safer for him to remain in the internment than to be released in the present acute circumstances of the war.

We therefore very regretfully refuse to grant him leave to submit objections.

[Underlined] LEAVE REFUSED

THE TRIBUNAL THEN PROCEEDED WITH OTHER BUSINESS.

[Dividing line.]

GOR/V/227. 12. H. IDE, 18/5/42.

This record is an excerpt of the transcript of the trial that reviewed Hideichiro Ide's objection to internment. Hideichiro 'Henry' Ide was a naturalised British subject and prominent silk merchant, importing quality Japanese silk into Australia.

Henry Ide was also an inventor. He submitted a patent application for the invention of an 'Improved method of and apparatus for external application of medicine' with Dr Tsunehiro Kubokawa. This patent application is held in the national archival collection.

Henry Ide was interned, along with over 1,000 other Japanese Australians, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese Imperial forces on 7 December 1941. At the time of his internment Henry was 'nearly 80 years', had been living in Australia for 50 years, and had been a naturalised British subject for 40 years.

Naturalisation is the act of granting someone citizenship in a country where they were not born. In this case, Henry was naturalised as a British subject because Australia did not yet offer Australian citizenship. Until 1949, to be an Australian meant being a British subject. Despite Henry's 40 years as a British subject, he was considered a potential security risk due to his Japanese ancestry and interned during the Second World War.

Henry objected to his internment and a trial was conducted to consider his case for release. The pages above show the caution and sometimes hostility with which people of Japanese ancestry were treated during this time. Of note during Henry's trial is the focus on him being respected as an elder in the Japanese-Australian community. At one point he was asked 'are you not one of the leading members of the Japanese community?' to which he replied 'of course, I am the oldest; they all respect me.' This was later used as key evidence of Henry's 'intimate connection with Japan' and therefore grounds against him being released.

Another factor that was discussed were his children, 2 of whom served in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) during the Second World War. However, the tribunal panel decided that no 'glory or reflected righteousness' should be gained by Henry; that his children serving in the 'Forces' was in no way attributable to Henry, his values or the way he brought up his children.

Henry was released from internment on 1 January 1943 and put under house arrest. Henry Ide's experience is similar to that of many Japanese Australians who were interned during the Second World War.

The presumption of innocence is the idea that a court should assume a person is innocent until they are proven guilty.

Why do you think the presumption of innocence is a key part of a fair trial? Based on this record, does Henry Ide appear to have been presumed innocent or guilty?

Learn how to interpret primary sources, use our collection and more.