Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that the National Archives' website and collection contain the names, images and voices of people who have died.

Some records include terms and views that are not appropriate today. They reflect the period in which they were created and are not the views of the National Archives.

[page 1]

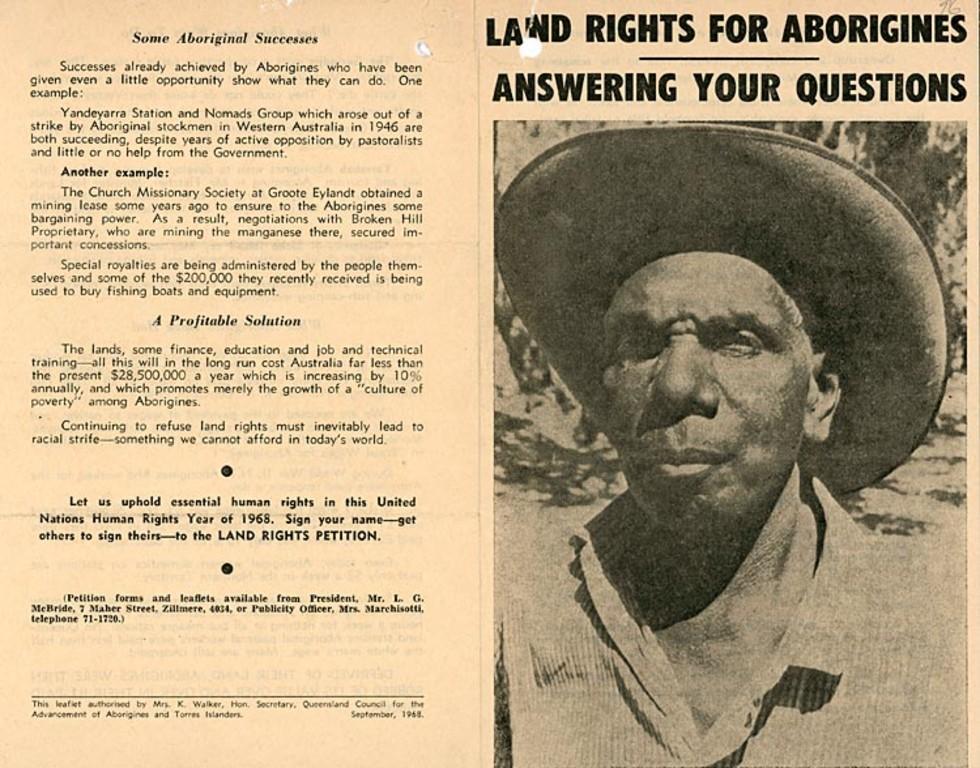

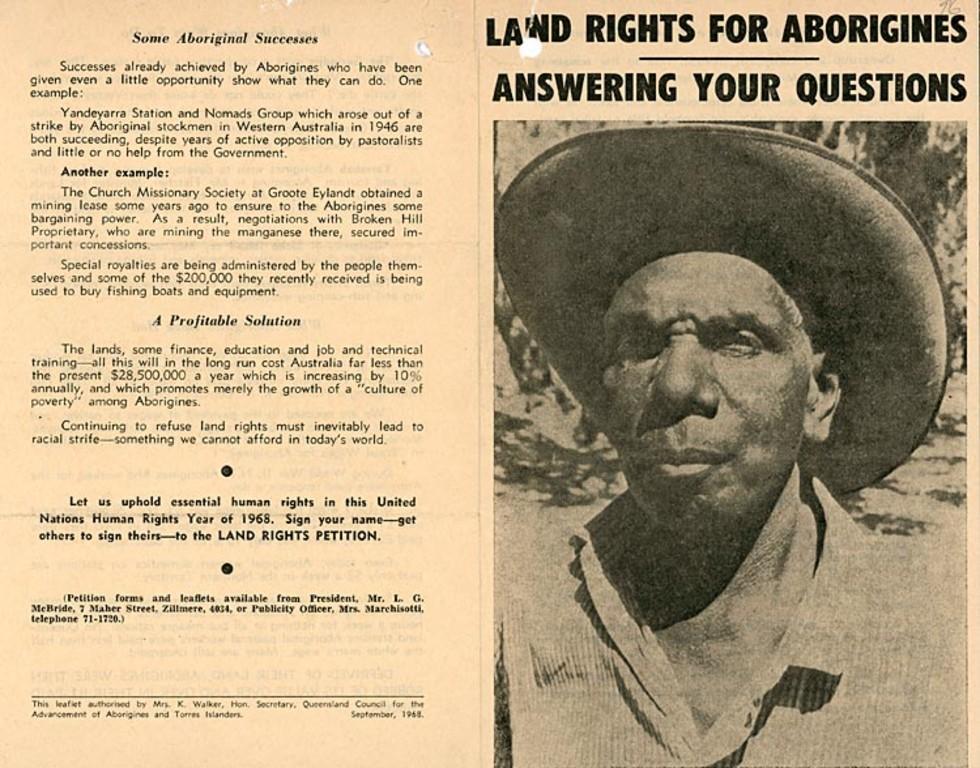

[The page is split in half. In its original form, it would have formed the back and front pages of a small booklet when folded.]

[Italicised, bold] Some Aboriginal Successes [end italicised, bold]

Successes already achieved by Aborigines who have been given even a little opportunity show what they can do. One example:

Yandeyarra Station and Nomads Group which arose out of a strike by Aboriginal stockmen in Western Australia in 1946 are both succeeding, despite years of active opposition by pastoralists and little or no help from the Government.

[bold] Another example: [end bold]

The Church Missionary Society at Groote Eylandt obtained a mining lease some years ago to ensure to the Aborigines some bargaining power. As a result, negotiations with Broken Hill Proprietary, who are mining the manganese these, secured important concessions.

Special royalties being administered by the people themselves and some of the $200,000 they recently received is being used to buy fishing boats and equipment.

[Italicised, bold] A Profitable Solution [end italicised, bold]

The lands, some finance, education and job and technical training – all this will in the long run cost Australia far less than the present $28,500,000 a year which is increasing by 10% annually, and which promotes merely the growth of a "culture of poverty" among Aborigines.

Continuing to refuse land rights must inevitably lead to racial strife – something we cannot afford in today's world.

[bold] Let us uphold essential human rights in this United Nations Human Rights Year of 1968. Sign your name – get others to sign theirs – to the LAND RIGHTS PETITION [end bold]

(Petition forms and leaflets available from President, Mr. L. G. McBride, 7 Maher Street, Zillmere, 4034, or Publicity Officer, Mrs. Marchisotti, telephone 71-1720.)

[line break]

[subtext] This leaflet authorised by Mrs K. Walker, Hon. Secretary, Queensland Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Islanders. September 1968. [end subtext].

[title] LAND RIGHTS FOR ABORIGINES

ANSWERING YOUR QUESTIONS [end title]

[Inserted is a black and white photo of Vincent Lingiari, the Gurindji leader. He is in a broad brimmed hat and a loose work shirt. He is looking towards the camera.]

[end page 1]

[page 2]

[The page is split in half. In its original form, it would have formed the inside pages of a small booklet.]

[Italicised, bold] What Lands do Aborigines and Islanders Want? [end italicised, bold]

Ownership and communal freehold title to the [bold] remaining [end bold] Aboriginal Reserves, Missions and Settlements.

And in cases where tribal consciousness still exists, as with the Gurindji people, ownership and freehold title to tribal territory.

[Italicised, bold] Will Land Rights of White Australians be Affected? [end italicised, bold]

No. The land the Aborigines are asking for is land they now occupy. In Queensland the lands required by Aborigines, though occupied by them, are owned by the Crown. For instance, Cherbourg, Yarrabah, Palm Island, Bamaga, etc.

[Italicised, bold] The Gurindjis and the Commonwealth [end italicised, bold]

The Gurindjis have petitioned the Federal Government for 500 square miles of Wave Hill Station which covers 6,158 square miles, in order to set up their own cattle station. The area they want – and where they now reside – is the centre of their sacred tribal land.

Federal Cabinet has told them they can go and live on the Drovers' Common at the Government Welfare Reserve some miles from Wave Hill. [bold] This land is not part of Wave Hill Station [end bold] and is bare, stony, barren and useless for agriculture or grazing. Even if Aborigines did buy and build their own homes on blocks of land there, they would probably not be given freehold titles.

Vestey's and other pastoralists are very pleased with the Government's decision, which sets [bold] no new [end bold] precedents.

[Italicised, bold] Who are Vestey's? [end italicised, bold]

Vestey's, a huge international company with properties in 70 countries, leases Wave Hill and other N.T. Stations from the Crown and employs all the Gurindjis. Their Wave Hill lease expires in the year 2004.

Their interest in the Australian pastoral industry began 50 years ago.

Vestey's occupy 40,000 square miles of Australian land, 31,000 square miles of it in the Northern Territory, the rest in Western Australia and Queensland.

For the 31,000 square miles they occupy in the Northern Territory they pay an [bold] average yearly rental of 50 cents a square mile [end bold] to the Government.

[Italicised, bold] What Aborigines Want to Do [end italicised]

The Gurindjis [end bold] want a co-operative cattle station. They say, and rightly, "Vestey's can't hear the cattle die. But [bold] we [end bold] can hear the cattle die." They could not do worse than Vestey's, whose inefficient methods have destroyed much land and caused serious erosion. One of Vestey's stations has been resumed by the W.A. Government because of this.

[Bold] Yarrabah [end bold] Aborigines wish to develop farming, timber, fishing and tourism. According to Mr Fletcher, Minister for Lands and Tourism, Yarrabah Aborigines have "made some thousands of dollars" from tourist activities. But this money is held by the Government.

Aborigines at [bold] Elcho Island [end bold] say they want a grant of their tribal land to develop timber, minerals and fishing production.

[Bold] Torres Straits Islanders [end bold] want their own pearling, prawn fishing and fish-canning industries.

[Italicised, bold] What Aborigines Have Had [end italicised, bold]

In 1918 the wage for an N.T. Aboriginal pastoral worker was set at 5/- a week. But pastoralists mostly ignored this regulation. For years Vestey's paid no wages at all. They told Anthropologist Professor R. M. Berndt in 1946: -

"We are opposed to the payment of wages to natives, and consider that there has been enough trouble with wage systems. Money seems to be the root of all evil." (Quoted by Frank Stevens in "Equal Wages for Aborigines.")

During World War II, N.T. Aborigines who worked for the Army were paid tenpence a day.

In 1947 when the basic wage was £5, N.T. Aborigines were paid £1 a week – 20% of the basic wage. But in 1965 they were paid £2/8/3, which was [bold] only 15% [end bold] of the basic wage.

Even today, Aboriginal women domestics on stations are paid only $2 a week in the Northern Territory.

Similar conditions applied in Queensland where for many years Aborigines on Missions and Settlements had to work 32 hours a week for nothing at all but meagre rations. On Queensland stations Aboriginal pastoral workers were paid less than half the white man's wage. Many are still underpaid.

[Capitalised] DEPRIVED OF THEIR LAND, ABORIGINES WERE THEN ROBBED OF ITS VALUE OVER AND OVER IN THEIR ILL-PAID LABOUR. [end capitalised]

These two pages are the front and back of a 1968 pamphlet titled Land Rights for Aborigines – Answering Your Questions which urged readers to sign a land rights petition. The pamphlet outlines the position of Aboriginal peoples in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. It explains what land Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples want and what they hope to do with it.

The pamphlet particularly focuses on the Gurindji people and the Wave Hill a pastoral lease held by the Vestey Group, a British pastoral conglomerate owned by Lord Vestey. A photograph of Vincent Lingiari, the Gurindji leader, features on the front cover. The pamphlet was authorised by Kath Walker, later known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

Learning resource text © Education Services Australia Limited and the National Archives of Australia 2010.

Learn how to interpret primary sources, use our collection and more.