Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that the National Archives' website and collection contain the names, images and voices of people who have died.

Some records include terms and views that are not appropriate today. They reflect the period in which they were created and are not the views of the National Archives.

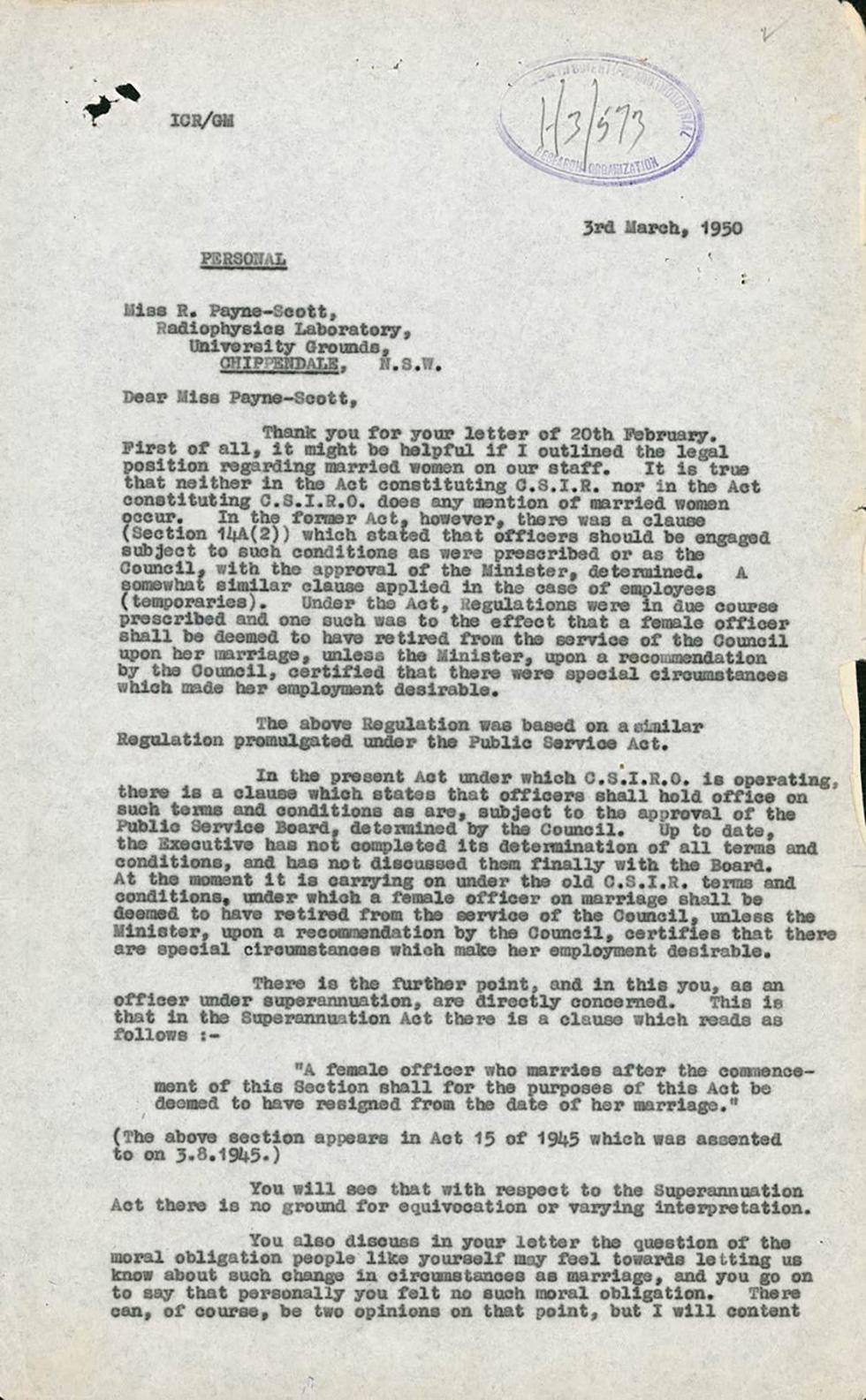

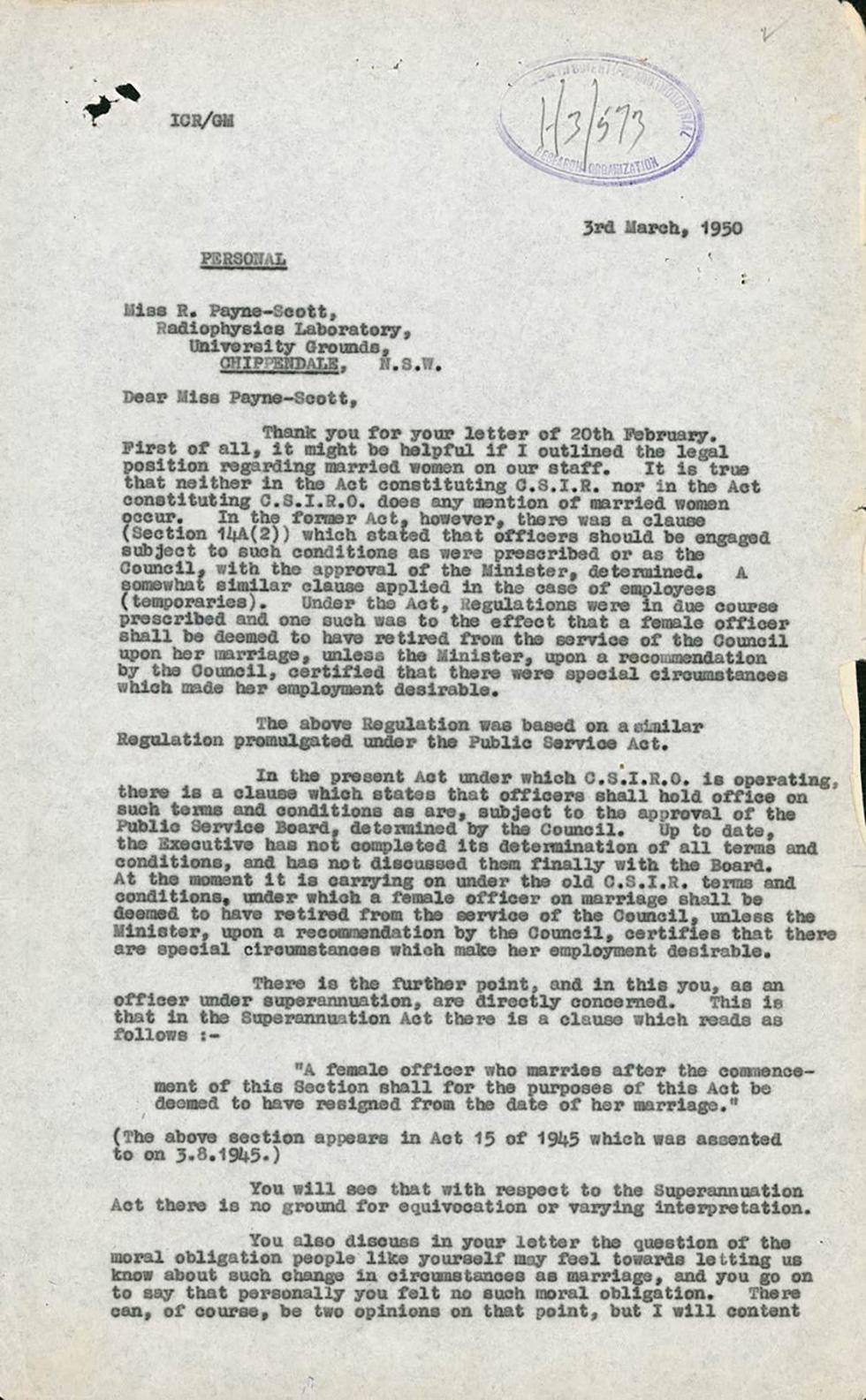

[Page 1.]

ICR/GM

[Stamped in purple ink: 'COMMONWEALTH SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH ORGANIZATION', with handwritten reference number 'H3/573'.]

3rd March, 1950

PERSONAL [underlined.]

Miss R. Payne-Scott,

Radiophysics Laboratory,

University Grounds,

CHIPPENDALE [underlined], N.S.W.

Dear Miss Payne-Scott,

Thank you for your letter of 20th February. First of all, it might be helpful if I outlined the legal position regarding married women on our staff. It is true that neither in the Act constituting C.S.I.R. nor in the Act constituting C.S.I.R.O. does any mention of married women occur. In the former Act, however, there was a clause (Section 14A(2)) which stated that officers should be engaged subject to such conditions as were prescribed or as the Council, with the approval of the Minister, determined. A somewhat similar clause applied in the case of employees (temporaries). Under the Act, Regulations were in due course prescribed and one such was to the effect that a female officer shall be deemed to have retired from the service of the Council upon her marriage, unless the Minister, upon a recommendation by the Council, certified that there were special circumstances which made her employment desirable.

The above Regulation was based on a similar Regulation promulgated under the Public Service Act.

In the present Act under which C.S.I.R.O. is operating, there is a clause which states that officers shall hold office on such terms and conditions as are, subject to the approval of the Public Service Board, determined by the Council. Up to date, the Executive has not completed its determination of all terms and conditions, and has not discussed them finally with the Board. At the moment it is carrying on under the old C.S.I.R. terms and conditions, under which a female officer on marriage shall be deemed to have retired from the service of the Council, unless the Minister, upon a recommendation by the Council, certifies that there are special circumstances which make her employment desirable.

There is the further point, and in this you, as an officer under the superannuation, are directly concerned. This is that in the Superannuation Act there is a clause which reads as follows: -

"A female officer who marries after the commencement of this Section shall for the purposes of this Act be deemed to have resigned from the date of her marriage.""

(The above section appears in Act 15 of 1945 which was assented to on 3.8.1945.)

You will see that with respect to the Superannuation Act there is no ground for equivocation or varying interpretation.

You also discuss in your letter the question of the moral obligation of people like yourself may feel towards letting us know about such change in circumstances as marriage, and you go on to say that personally you felt no such moral obligation. There can, of course, be two opinions on that point, but I will content

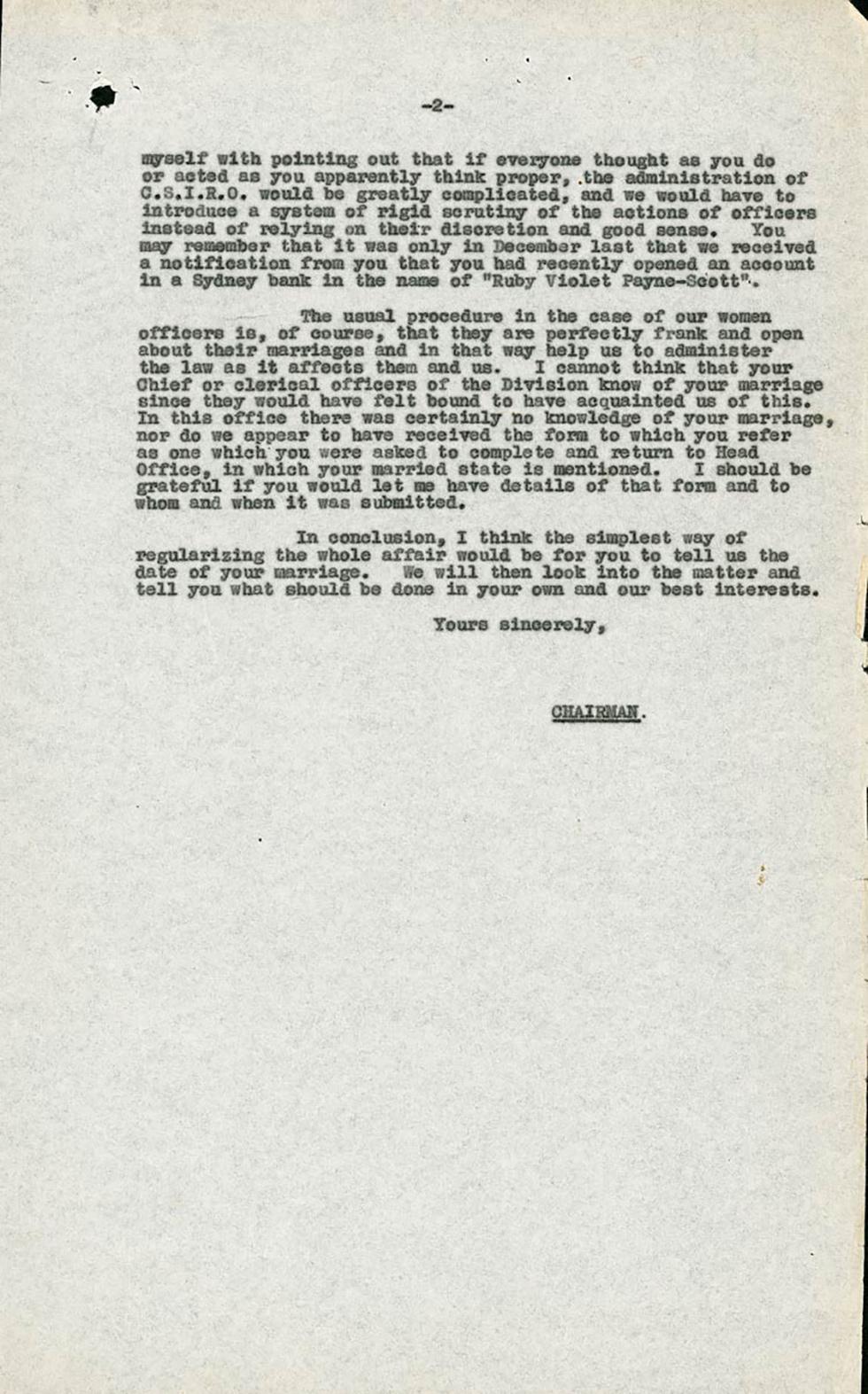

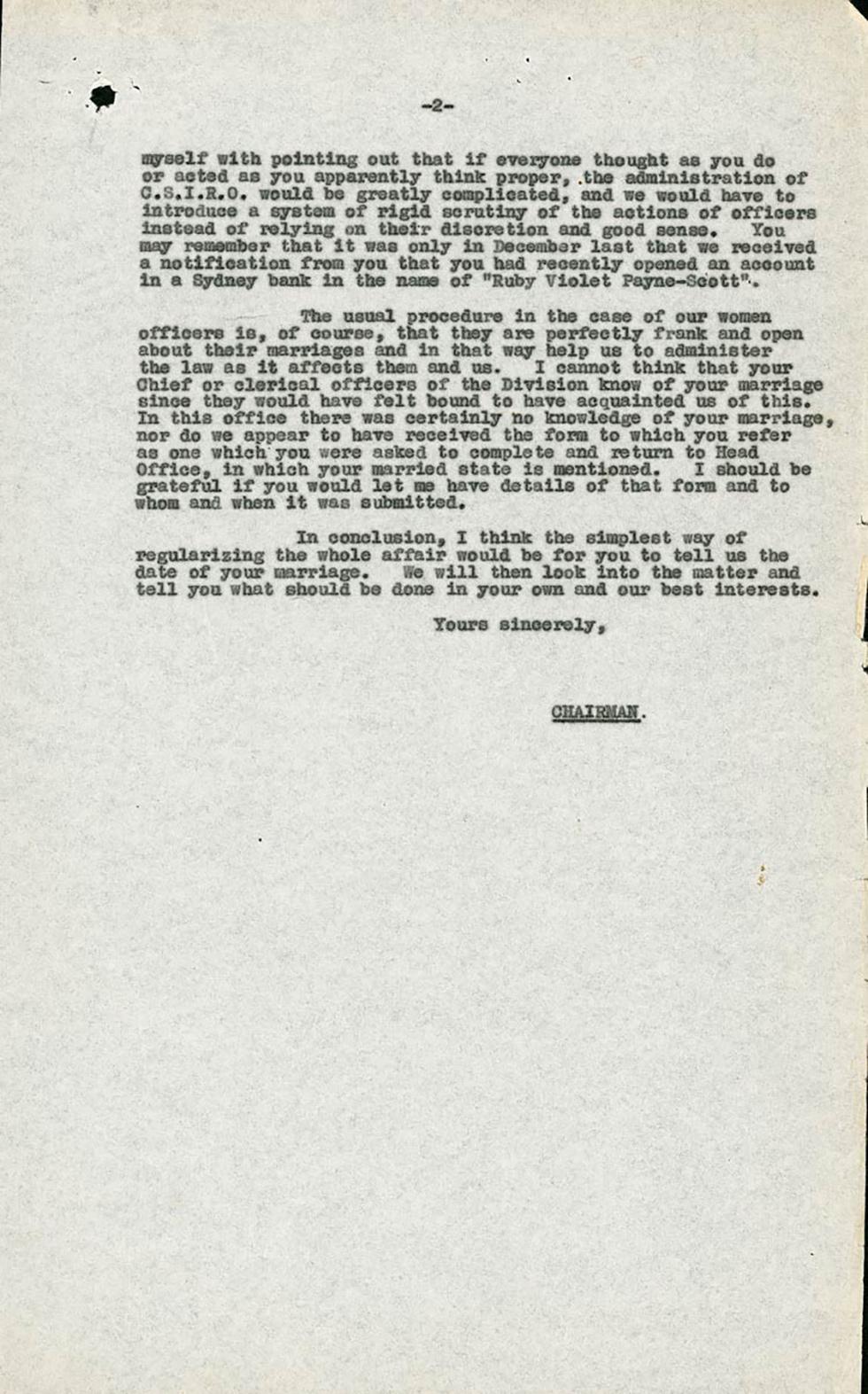

[Page] -2-

myself with pointing out that if everyone thought as you do or acted as you apparently think proper, the administration of C.S.I.R.O. would be greatly complicated, and we would have to introduce a system of rigid scrutiny of the actions of officers instead of relying on their discretion and good sense. You may remember that it was only in December last that we received a notification from you that you had recently opened an account in a Sydney bank in the name of "Ruby Violet Payne-Scott".

The usual procedure in the case of our women officers is, of course, that they are perfectly frank and open about their marriages and in that way help us to administer the law as it affects them and us. I cannot think that your Chief or clerical officers of the Division know of your marriage since they would have felt bound to have acquainted us of this. In this office there was certainly no knowledge of your marriage, nor do we appear to have received the form to which you refer as one which you were asked to complete and return to Head Office, in which your married state is mentioned. I should be grateful if you would let me have details of that form and to whom and when it was submitted.

In conclusion, I think the simplest way of regularising the whole affair would be for you to tell us the date of your marriage. We will then look into the matter and tell you what should be done in your own and our best interests.

Yours sincerely,

CHAIRMAN. [underlined.]

This letter, which forms part of the personnel file of pioneer radiophysicist Ruby Violet Payne-Scott, was sent to Payne-Scott by her employer, Dr Ian Clunies Ross, Chairman of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). The letter, dated 3 March 1950, is a response to Payne-Scott’s written objection to the treatment of herself and other married women in the Commonwealth Public Service.

Learning resource text © Education Services Australia Limited and the National Archives of Australia 2010.

Learn how to interpret primary sources, use our collection and more.