Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that the National Archives' website and collection contain the names, images and voices of people who have died.

Some records include terms and views that are not appropriate today. They reflect the period in which they were created and are not the views of the National Archives.

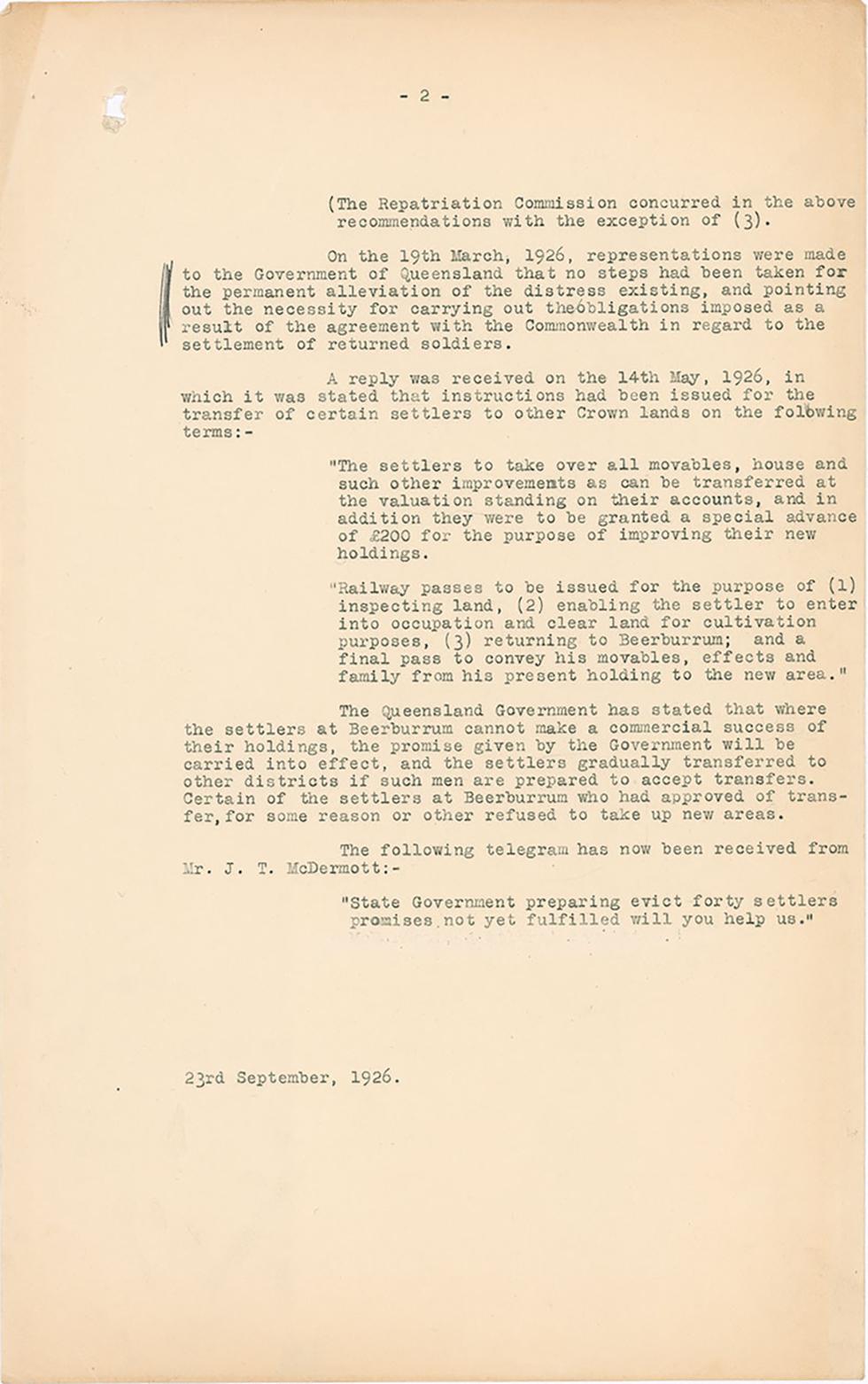

This two-page memorandum from the Prime Minister’s Department, dated 23 September 1926, concerns the Beerburrum soldier settlement scheme in Queensland. It was written to brief the Prime Minister after a member of the Beerburrum scheme sent a telegram requesting Australian Government assistance. The memorandum provides a history of the soldier settlement scheme at Beerburrum, indicating that many soldiers settled under the scheme had not been successful in farming the land and were experiencing distress. It also explains the shared responsibilities of the Queensland and federal governments and describes correspondence between the two governments regarding assistance for the settlers.

Learn how to interpret primary sources, use our collection and more.