The biggest issue we had was that people didn't believe we could do it. We'd set a target, a stretch goal out there of 100 megabits per second. The current technology was 100 times slower. People just didn't believe it was possible.

My name is Terry Percival. I live in Sydney, and I'm a research scientist and research engineer who worked at CSIRO as part of the team that invented wi-fi technologies.

When I was at university, I was looking at various options to do with my degrees and looking around at things like the Parkes radio telescope. It really made me think these are amazing machines – I wonder what makes them work.

The original team there were five of us, Dr John O'Sullivan, Diet Ostry, Graham Daniels, John Deane and myself. John O'Sullivan and I had done our PhDs at Sydney University, building a radio telescope called the Fleurs radio telescope out at Badgerys Creek, which is an array of 72 antennas.

We had a mixture of skills. We'd worked a lot on complex systems, starting in radio astronomy. I'd worked also in satellite communications. Others had worked in data communications. We had a team of people who had vast experience in complex radio systems.

People wanted to be connected wherever they went. It was a really complex problem to solve. We have people saying, 'Your technology is so complicated it will never fit in a portable device. It will consume too much power. The batteries will go flat in five minutes.'

People really didn't believe that what we were doing was possible, but because we built these systems before we knew that what we were doing was achievable.

Wi-fi was one piece of the puzzle, but it's the one that was really difficult to do. And it's, I guess, the one that had the biggest impact for us in CSIRO and Australia.

Wi-fi is a high-speed communication system that enables portable devices like phones and laptop computers and iPads to connect to the internet. It goes through a modem like this, which is plugged into the wall, and radio communications go between the devices and this modem.

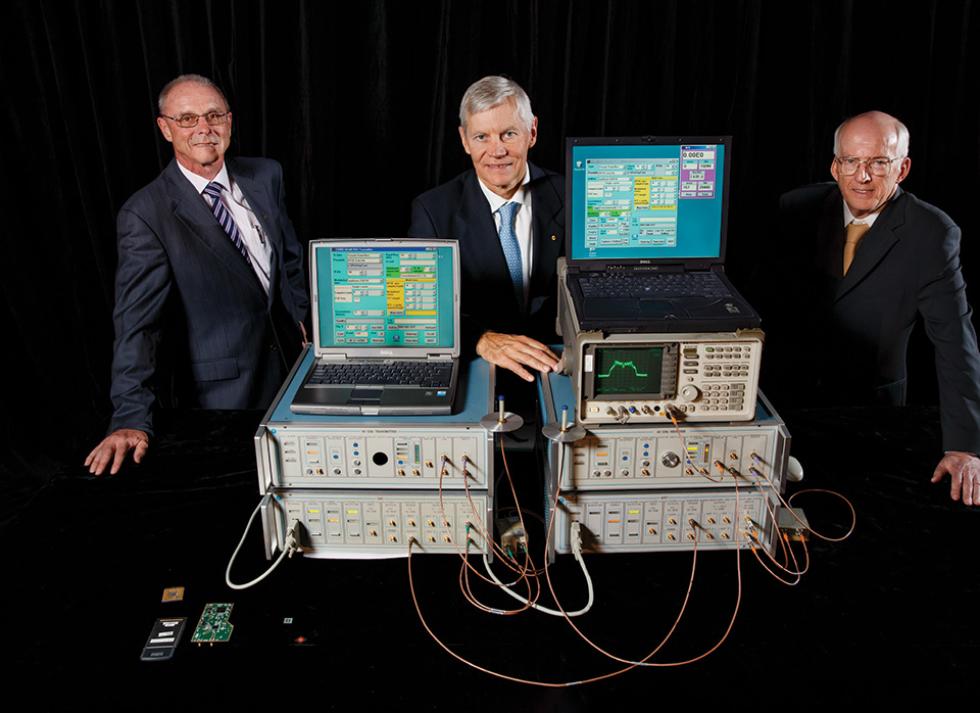

This is one of the early prototypes we built. This enabled us to prove that our system would work reliably.

We mounted one transmitter in the roof and the other on a trolley that we pushed around various office space.

Having got this far, we were still getting pushback, so we decided we had to take that big test bed and turn it into something smaller.

This took seven years. We went from a prototype that was this big, to a prototype that was that big, to a prototype that was that big.

And suddenly the world changed because people realised it did work, and it was able to be put on a little card that would fit inside a PC.

The institution of electrical and electronic engineers in the US issued a new standard for in-building wireless, and it was an exact copy of our patent and our prototype. But we had the patent, which was already granted four years previously.

We started the lawsuit in the US to sue all of the companies that were selling products.

It came to culmination in a big trial in Texas. I was giving evidence in court, and I was feeling pretty exhausted at the end of the time.

We were sitting in our offices on a Sunday morning, after one week of trial, and suddenly there was an almighty cheer coming from outside my office. I stuck my head out the door, and everyone cheered and said, 'We've won! We've won!' They've all given up.'

At this stage, everyone had settled the lawsuit, and in the first tranche CSIRO got $200 million worth of royalties paid.

Back in 2012, John O'Sullivan and I were invited to the Inventors Award. John and I were sitting there looking at each other when the nominations were read out by a gentleman called Professor Rubik, who was better known for inventing a little toy called the Rubik's Cube.

The European Innovator Award 2012 goes to Dr John Sullivan and Terence Percival.'

We won the European Inventors Award for the invention of wi-fi technologies. We saw the advent of laptop computers, personal tablets. If you could get wireless connectivity into them high-speed, it would make a big difference to things like education. We discussed lots of scenarios where it might be used. Classrooms was one area. Obviously, the home office, businesses, even inside aircraft.

When the COVID pandemic hit, it was amazing how many new applications suddenly had to appear – and obviously remote learning, which had been traditionally used in Australia with School of the Air. Now suddenly the whole of Australia had to embrace this sort of technology. And this wouldn't have been possible without this universal communication system that we'd dreamed of 30 years ago.

It's really a success of knowing that you worked together as a team and achieved a really good outcome.

It's a great satisfaction when something that you've worked on actually gets used.