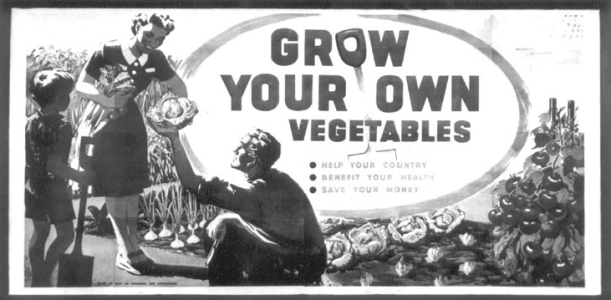

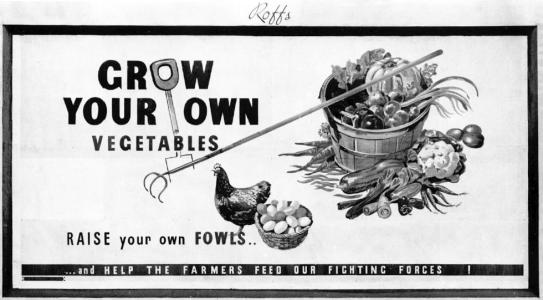

Australia's suburban backyards have been home to an assortment of agricultural enterprises over the years: poultry coops, vegetable patches, lemon trees reaching over eaves, passionfruit draping over side fences. Australians have grown their own food for a variety of reasons, including thrift, leisure, enjoyment and food quality. In a time of war, the production of food in suburbs from North Perth to South Melbourne became an activity of national importance.

The impact of war

During the early years of World War II, there was actually a surplus of commercially produced food in Australia due to reduced shipping spaces and export markets. However, after Japan entered the war and American food supplies were diverted to Russia, Australia began to change its food production and consumption patterns in order to supply other countries (primarily the UK) and the increasing number of Allied personnel in the region. From 1942, the number of farm labourers decreased due to war enlistments. Meat rationing reduced the availability of an important component of Australian diets, and civilian food supplies were diverted to meet the needs of the influx of servicemen into Australia.

By 1942 Australia was facing significant shortfalls of milk (by 180 million gallons), meat (by 150,000 tonnes, with civilian rationing), eggs (by 29 million dozen), and canned fruit (by 1.22 million cases). The nation's larders were looking altogether too bare for comfort.

As commercial producers struggled with shortages, efforts to improve the health and efficiency of the population were stepped up. The demands of war required that citizens be fit not only to increase the rate of production but also to defend the nation, should it come to that. Drawing on the increasingly commonplace language of nutritional science, manufacturers placed advertisements declaring that 'Never in the history of this free land has a well-balanced diet been so vitally important to all of us', and urging people to ‘Eat foods that help make Australia strong.'