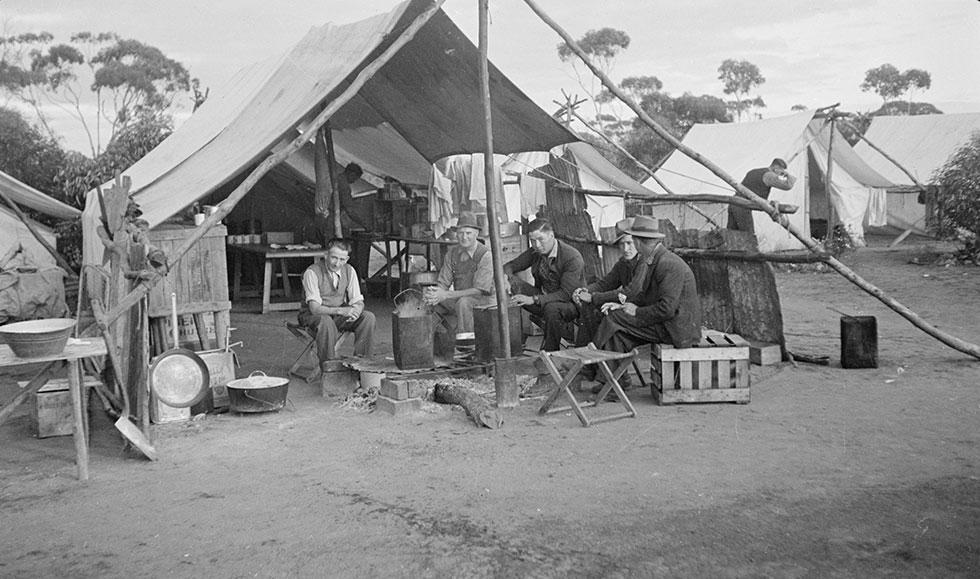

During the Second World War, Commonwealth railways struggled to attract skilled workers.

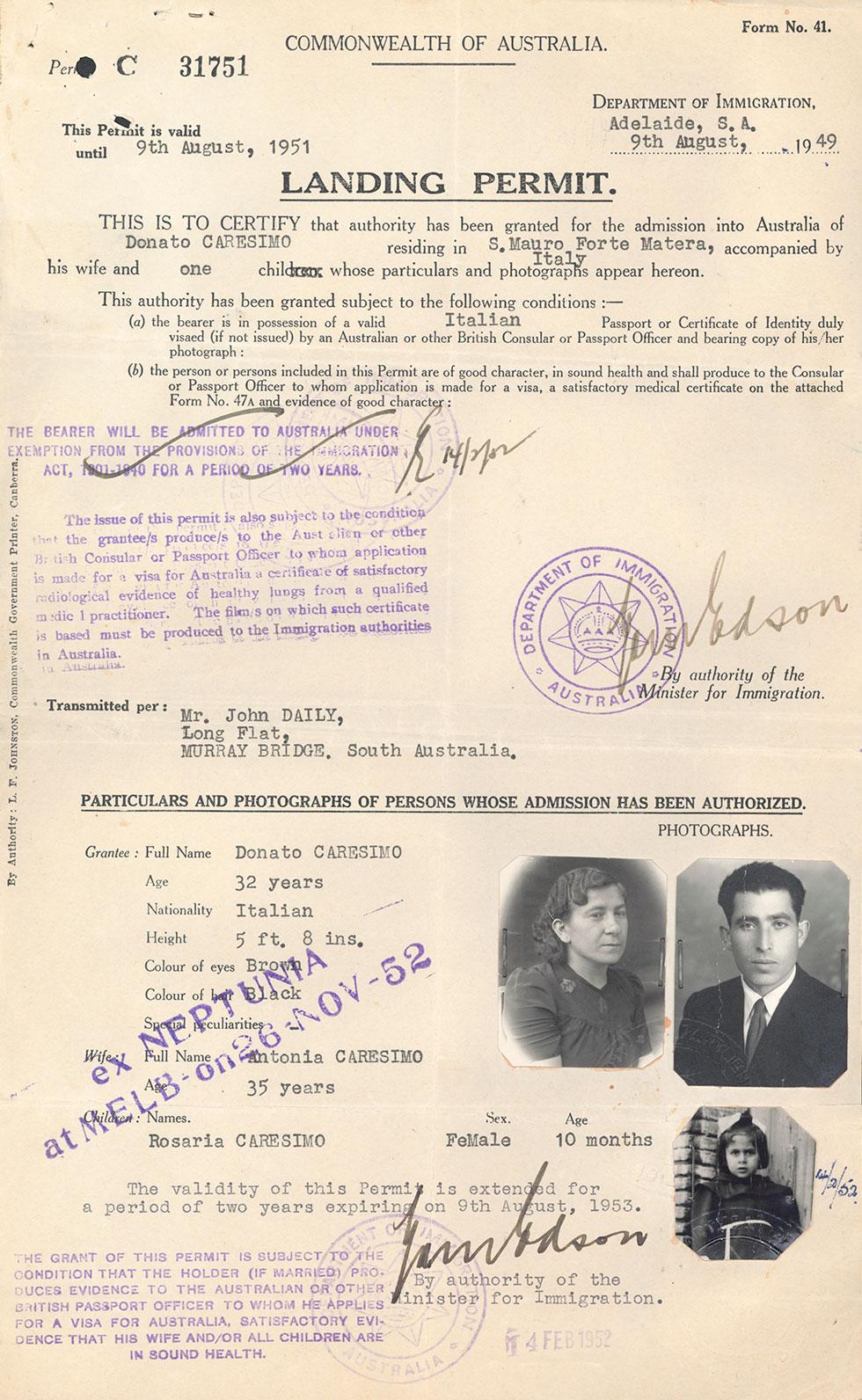

They were needed to continue the maintenance and wartime track work of the Trans Australian Railway. The solution to the workforce shortage? Prisoners of war.

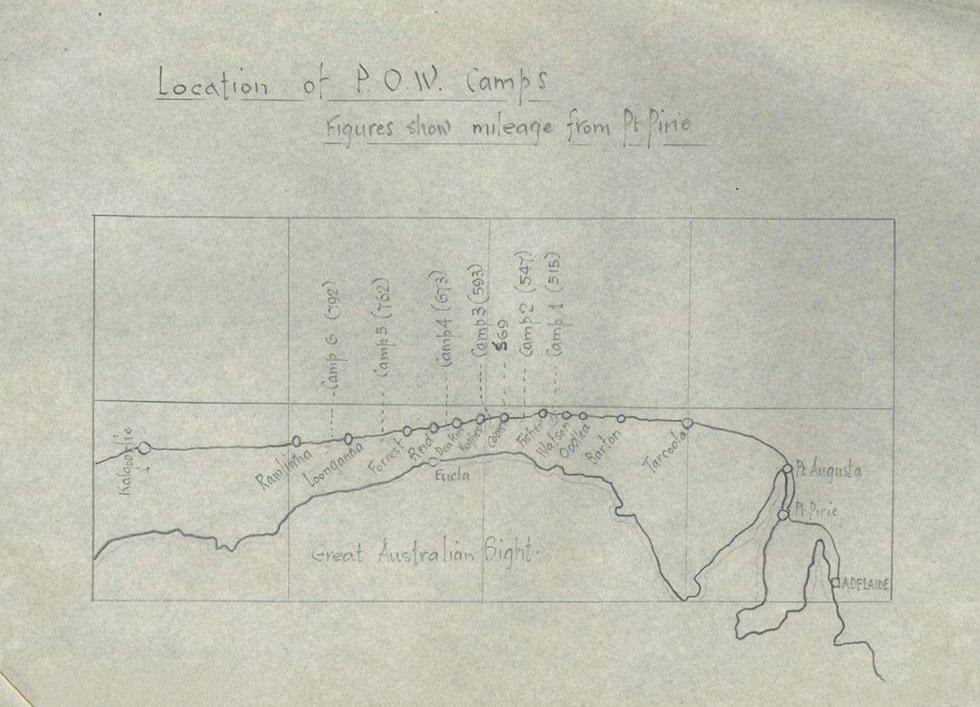

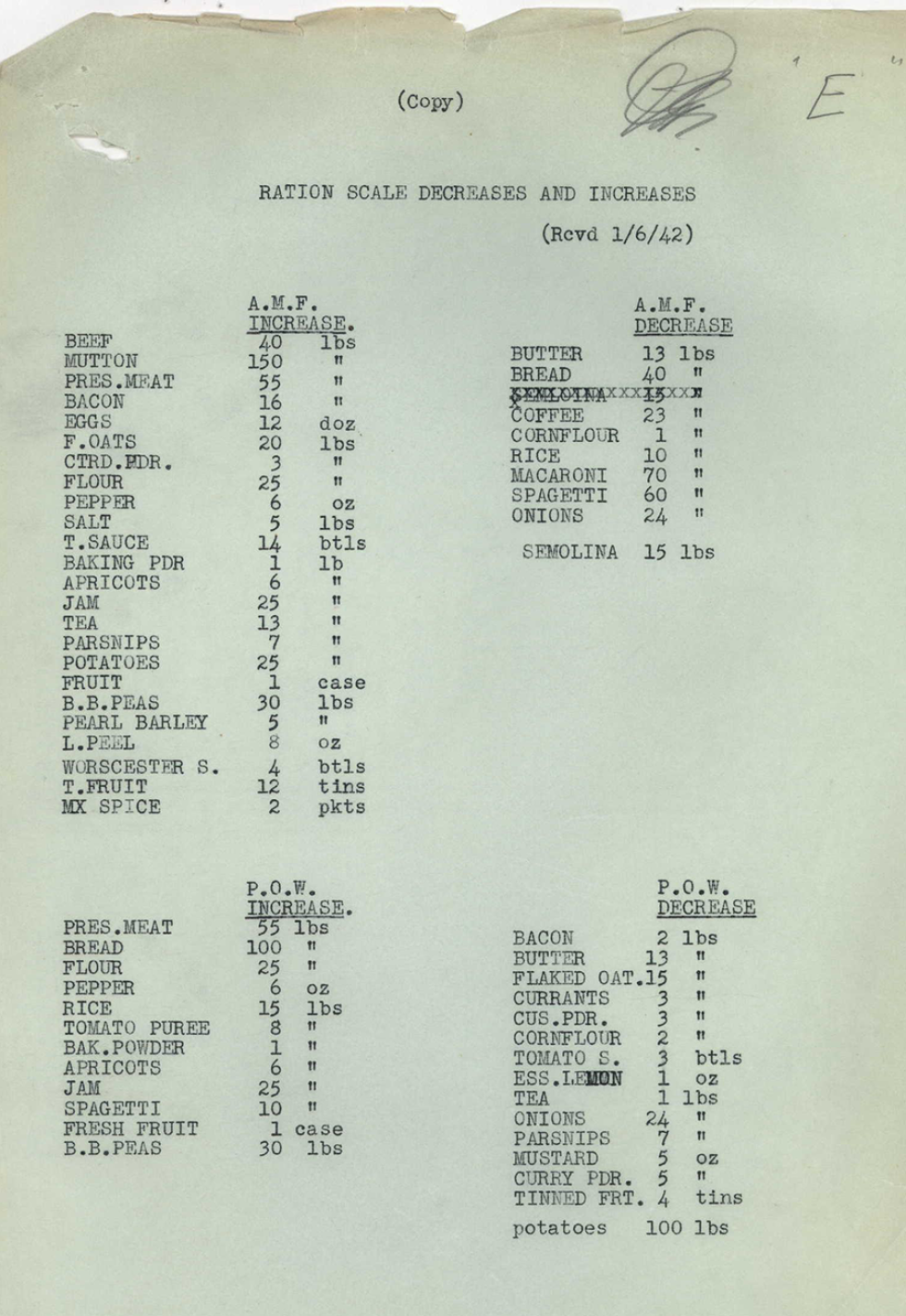

In April 1942, a group of 300 Italian prisoners of war were assigned to work in 6 railway camps along the Trans Australian Railway. A military camp was also established at Cook in South Australia, for the headquarters staff to oversee the POW labour force. It was hoped that these men would expedite sleeper renewals on the railway and keep the momentum of the building of the line.