Joseph Benedict (Ben) Chifley's victor Robert Menzies was sworn in after the federal election 9 days before. The attempted nationalisation of the private banks, and the continuation of petrol rationing, were crucial problems for Labor. As well, the development of the Cold War made the Labor Party vulnerable to allegations of being sympathetic to Communism.

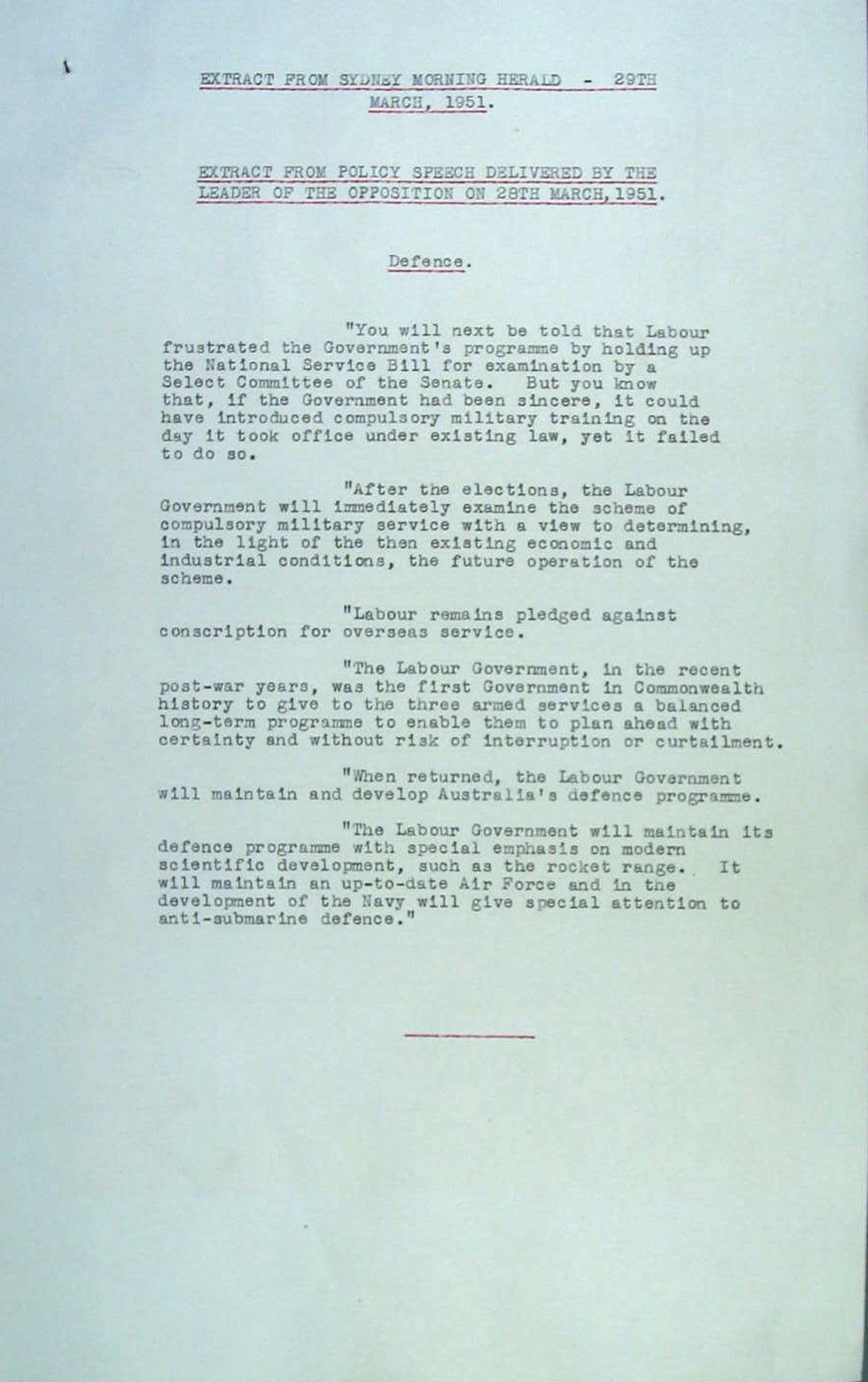

A Defence Department document with published extracts from Ben Chifley’s speech on 28 March 1951, in his last election campaign. NAA: A5954, 2143/3, p.37

Menzies was not slow to make the most of this opportunity. His government introduced a Bill to ban the Communist Party in Australia. Chifley opposed the ban as impractical, and as an affront to civil liberties, but it divided the Labor Party. When the proposed law was disallowed by the High Court, it became the major issue at the federal election on April 1951 when Chifley suffered his second electoral defeat as leader.

2 months later, Chifley died from a heart attack in his Canberra hotel on 13 June 1951.

Opposition Leader

In December 1949, Chifley remained leader of the Labor Party, promising to do the job ‘in no half-blooded way’. He was not confident of the capacity of his deputy, HV (Bert) Evatt, to keep the party united, nor that there were leaders ready among the then Labor parliamentarians.

Few would have predicted in 1949, that Robert Menzies would stay on for a record 17 years as Prime Minister. Certainly Chifley thought he had a good chance of toppling Menzies at the next poll. He told a meeting of trade union officials in January 1950, ‘not to be disheartened by the election result as Labor would rise again’. But the cramped and fearful politics of the Cold War increasingly impinged on parliamentary debates in Canberra. The Cold War also affected the debates within the Labor Caucus, where there was a solid core of support for the anti-Communist measures proposed by Menzies.

In line with his election policy, in April 1950 Menzies introduced a Bill to ban the Communist Party in Australia. The Bill provided for the dissolution of the party and the seizure of its assets. It also provided that people declared by the government to be Communists would be barred from trade union office and from employment by the Commonwealth. Their homes could be raided without warrant by police searching for evidence against them, and declared people would have to prove their innocence, rather than the police having to prove their guilt.

Although this was in conflict with Menzies’ firm belief in the rule of English law, he claimed extraordinary times had created the possibility of a new world war, with the Soviet Union and China ranged against the western powers. Communist Party, it was claimed, influence in trade unions was a threat to the nation if war erupted with a Communist nation. Menzies also argued he had an electoral mandate for imposing such a ban.

Although Chifley was completely opposed to the Bill, some of his colleagues could see some merit in it and were prepared to let it pass. Accordingly, Chifley had to move carefully in opposing it. He focused on the civil liberty aspects that denied those declared to be Communists the normal protections of Australian law. Chifley freely acknowledged that it might be ‘politically bad’ to oppose the Bill in the context of the Cold War hysteria whipped up by the government. But he refused to give in to what he described as ‘a few fanatics’ within the Labor Party who wanted it to become law.

When the Labor-controlled Senate forced through some amendments, and academics and others voiced their concerns, Menzies grudgingly agreed to some changes in the proposed law. Then hostilities broke out on the Korean peninsula and Australian forces were committed to the conflict. Menzies claimed the war in Korea involved the ‘fate of mankind’. He re-introduced the Bill, declaring it involved the ‘security of Australia’ and threatened a double dissolution if the Senate refused to pass it. For a time, Chifley managed to maintain Labor’s opposition to the Bill, but the federal executive finally decreed it be allowed to pass. It was a humiliating reversal for Chifley, who counselled colleagues to accept it ‘on the chin’ and ‘go forward’ for the sake of the unity of the labour movement.

The law was enacted on 19 October 1950 and was quickly challenged by the Waterside Workers Federation. They engaged HV (Bert) Evatt to argue their case before the High Court. Denied his double dissolution on this Bill, Menzies tried again with a Bill to wind back Chifley’s Banking Act of 1945. Chifley declared he would resign if the executive directed him to let this legislation pass. Then, on 26 November in Bathurst, Chifley suffered a heart attack that put him in hospital. It was almost on the anniversary of John Curtin’s heart attack in Melbourne 6 years before.

Jubilee year 1951

Chifley returned to Canberra early in February for the start of the next parliamentary session. With no obvious replacement except HV (Bert) Evatt, Chifley was resigned to staying at his post until a more suitable successor appeared. But Menzies was intent on a double dissolution and seized his chance when the Labor Senators referred the banking bill to a select committee. Concurring with the Prime Minister that this constituted a refusal to pass the legislation, Governor-General Sir William McKell dissolved the parliament.

The election was set for 28 April, and the Communist Party in Australia became the major issue after Evatt successfully argued for the High Court to reject the dissolution law. Chifley increased his own majority in Macquarie, but could only manage to retrieve 5 extra seats for Labor, leaving Menzies with a comfortable majority. The government also managed to gain control of the Senate.

The strain of the election campaign took a further toll on Chifley’s health. He had always driven himself to and from Canberra, but now asked for a government driver on his doctor’s suggestion. In May, Chifley went to Melbourne to visit James Scullin, whose poor health had meant his retirement at the 1949 election. Chifley also met with his executor to check the details of his will. On 10 June 1951, he told delegates at the New South Wales Labor Party’s annual conference not to be disheartened by the defeats. He asked that members not desert their political ideals just because of the government’s scaremongering about Communism. ‘I could not be called a ‘young radical’, said Chifley, ‘but if I think a thing is worth fighting for, no matter what the penalty is, I will fight for the right, and truth and justice will prevail’. On 11 June, he was the sole candidate in the post-election Caucus ballot for the Labor leadership.

The next day, Chifley attended the ceremonial opening of the new parliament. That night he was one of the 3 former prime ministers to toast the 50-year-old Commonwealth at the Jubilee banquet. Chifley’s toast declared that no-one had ‘a greater reverence for the institution of Parliament’ than him.

Chifley had declined the invitation to attend the Jubilee Ball in King’s Hall in Parliament House the following evening, 13 June 1951. When the festivities began there, he was nearby in his room at the Hotel Kurrajong. After he phoned Elizabeth Chifley in Bathurst, she listened to the radio broadcast of the Ball, until a phone call from HV (Bert) Evatt telling her that Chifley had suffered a fatal heart attack. Robert Menzies’ announcement of the news in King’s Hall brought the Jubilee Ball to a sudden and shocked end.

Chifley’s body was laid in state in King’s Hall 2 days later, and 100s of people expressed their grief at the sad and sudden end to a life Chifley devoted to the service of his fellow Australians. Although Chifley had been denied the sacraments for 37 years, since his marriage in a Presbyterian church, his huge state funeral was held in Bathurst’s ornate Catholic Cathedral.

Chifley was buried in Bathurst, his home for all of his 66 years.

Sources

- Day, David, Chifley, Harper Collins, Sydney, 2001.

- McMullin, Ross, ‘Joseph Benedict Chifley’, in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland Press, Sydney, 2000.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Funeral of the late Mr Chifley, 1951, NAA: SP1008/1, 483/2/357