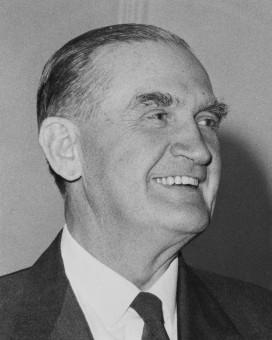

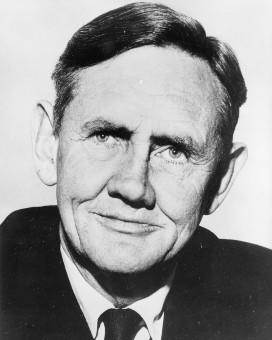

By the age of 12, Harold Edward Holt had lived in Sydney, near Nubba in the south-west of New South Wales, in Adelaide and in Melbourne. He then completed school at Wesley College in Melbourne and a law degree at the University of Melbourne. Holt worked as a solicitor, and furthered his interest in sport, debating, acting and politics.

He won a House of Representatives seat in 1935, and first became a minister at the age of 30. A promising young politician, he was dubbed ‘young Harold’ by his mentor, Prime Minister Robert Menzies. In Opposition from 1941 to 1949, Holt held senior portfolios during the next 16 years of the Menzies government. He was Minister for Immigration, Minister for Labour and National Service, Minister for the Melbourne Olympics, then from 1958, Treasurer.

Early years

Holt was the elder of the 2 children of schoolteachers Thomas and Olive (Williams) Holt. He was born in the Sydney suburb of Stanmore on 5 August 1908. He and his brother attended 4 different schools in Sydney, Nubba and Adelaide between 1913 and 1919. Then from 1920 to 1926, Holt finished school in Melbourne, where his father had become a theatre manager.

As a student at the University of Melbourne, Holt was outstanding in sports and debating, graduating in 1930 with a law degree. He worked first for a local firm of solicitors, and was admitted to the Bar in 1932, at the age of 24. Unable to make a living as a barrister during the Depression, he set up his own practice as a solicitor in 1933.

Holt’s father was then working with theatre, film and radio entrepreneur FW (Francis William) Thring, and with his brother in the Hoyts cinema chain. Holt’s interest and contacts in this world developed both his professional practice, and his social and political life. His friends included Norman and Mabel Brookes and another Wesley old boy, Robert Menzies, then Victoria’s Attorney-General.

‘Young Harold’

A star debater at the Prahran branch of the ‘Young Nationalists’, in 1933 Holt joined the United Australia Party (UAP). Formed 2 years before from a merger of the Nationalist Party and a dissident Labor group, the UAP was led by Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. In 1934, Holt was the party’s candidate for the federal seat of Yarra, standing against the sitting member, former Prime Minister James Scullin. At this federal election, Holt was unsuccessful. He also failed to win a state seat 6 months later, when he stood for the Victorian parliament.

After the sitting member died, Holt’s third attempt won him the federal seat of Fawkner in a by-election in 1935. For the next 4 years, he was a backbencher in the Lyons government, speaking frequently on a wide variety of subjects, including his favourite issues – health and physical fitness.

When Joseph Lyons died in April 1939, Country Party leader Earle Page was briefly Prime Minister. On 26 April, the United Australia Party elected Robert Menzies as the new leader, with William Hughes his deputy. Menzies gave Holt, just 30 years old, a junior Cabinet position assisting the Minister for Supply and Development (first Richard Casey and then Frederick Stewart). Supply and Development was a new department established in the months before the declaration of war in September 1939, to supply munitions and aircraft, and extend Australia’s defence industries. Holt lost this post in March 1940, as part of Menzies’ negotiations with Earle Page for a coalition ministry with 5 Country Party members. As the most junior minister, Holt was replaced by Arthur Fadden.

Between October 1939 and March 1940, Holt had 3 other brief Cabinet roles. He was minister assisting Robert Menzies with the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, and then minister assisting with Trade and Customs while the Prime Minister briefly held the portfolio after the resignation of John Lawson. Holt also acted as Minister for Civil Aviation and Air while James Fairbairn was overseas negotiating Australia’s role in the Empire Air Training Scheme.

After he lost his ministerial post to Arthur Fadden, Holt enlisted in the army on 22 May 1940. He trained as a gunner in the 2nd Australian Imperial Force for less than 5 months and never left Australian shores. In October he returned to Cabinet after the tragedy known as ‘the Canberra air disaster’. In the winter of 1940, 3 of Menzies’ senior Cabinet members, Geoffrey Street, James Fairbairn and Henry Gullet, were killed when their aeroplane crashed on the southern approach to Canberra.

Minister for Labour and National Service 1940–41

After the federal election in September 1940, the Menzies government remained in office only with the support of 2 Independents, Arthur Coles and Alex Wilson. In the new ministry, Holt became the first to hold the newly created portfolio of Labour and National Service. This new wartime department was established under national security regulations on 28 October 1940. Holt announced it in parliament as:

a central organisation that will make the most effective practical use of man-power and woman-power. The marshalling of those resources in order to obtain the maximum war effort for Australia, and a maximum degree of help and cooperation for Great Britain and the sister Dominions, is the primary objective of the new Department ...

This portfolio immediately involved Holt in major negotiations with maritime unions and employers over a series of waterside disputes. It was also his task to introduce a national child endowment scheme for second and subsequent children. As parliament’s only bachelor, he was widely featured in popular magazines like the Australian Women’s Weekly and Pix, which were unable to resist the opportunity to declare him ‘godfather of a million children’.

Out of government 1941–49

When Robert Menzies lost the leadership of the United Australia Party in August 1941, Country Party leader Arthur Fadden became Prime Minister. The Fadden coalition government was then defeated in a no-confidence motion on 3 October 1941, and the Governor-General commissioned Labor leader John Curtin to form a government.

No longer on the front benches, Holt resumed his part-time legal practice in Melbourne and continued to speak frequently in parliament. He was Opposition spokesman on industrial relations, and a principal supporter of the growing ‘anti-socialist’ movement. From 14 October 1943, Holt served on the parliamentary joint committee on war expenditure.

At the federal election in August 1943, Holt retained Fawkner, though the United Australia Party (UAP) was virtually annihilated. Since its first very successful election in 1931, the UAP had lost seats heavily to Labor in 1937 and 1940. Holt dubbed the 1943 result the ‘deathblow to the diehard Tories’. A month after the election, Robert Menzies replaced William Hughes as leader of the UAP, and took decisive action to build a durable anti-Labor political force. Holt strongly supported the name ‘Liberal’ chosen by the UAP parliamentarians, and was a foundation member of the new Liberal Party.

5 weeks before the surrender of Japan ended the 1939–45 war, Prime Minister John Curtin died. His deputy, Frank Forde, was Prime Minister until the Labor Party elected Ben Chifley as the new leader. At the election on 28 September 1946, the Labor government was again victorious – the new Liberal Party won only 15 House of Representatives seats. 10 days after this election, the wedding of Harold Holt and Zara Fell was held. Friends for more than 20 years, since before Zara Fell’s first marriage, the couple made their home in Melbourne with Holt adopting her 3 small sons.

Parliamentary broadcasting had commenced in July 1946, and Holt served on the joint parliamentary committee for the next 3 years. In August 1948, he was one of the Australian delegates to the Empire (from 1949 Commonwealth) Parliamentary Association. Meeting in London, delegates afterwards toured the British sector of the newly divided Germany. With delegates Dorothy Tangney and John Howse, Holt also attended a United Nations meeting in Paris in late October. The month before, an Australian, HV (Bert) Evatt, had been elected president of the United Nations General Assembly.

Minister for Immigration, and Labour and National Service

In 1949, the Chifley government increased the size of the House of Representatives from 75 to 121 (including a non-voting Member for the Australian Capital Territory). As a result, the Senate expanded from 36 to 60 seats. After the redistribution to form the new electorates, Holt became the candidate for Higgins, a new seat carved out of his former Fawkner electorate.

For the December 1949 election, the Liberal Party and Country Party ran a joint campaign building on Labor’s unpopularity for extended postwar austerities. The campaign also emphasised growing Communist activism in politics and in the trade union movement. Although Labor responded with a strong campaign, the Chifley government was voted out of office.

The new ministry, led by Robert Menzies and Arthur Fadden, was sworn in on 19 December 1949. At 41, Holt became Minister for Immigration and Minister for Labour and National Service, and ranked fourth in Cabinet seniority. The Chifley government had created a separate Department of Immigration in 1945 and under the first minister, Arthur Calwell, the emphasis for the first time moved away from British migration. Instead, the new policies included the resettlement of eastern Europeans displaced by the war.

With Holt in charge, in 1950 the department’s plan was to bring 200,000 migrants from Britain, Holland, Malta and Ireland to build an Australian population of 9 million by 1953. The initial emphasis was on family group migration but, from August 1951, workers for major public works such as the Snowy Mountains scheme were the focus. Holt also enthusiastically developed plans for annual citizenship conventions. The second of these, held 22–26 January 1951, marked the Commonwealth jubilee year and was opened by Prime Minister Robert Menzies at the Albert Hall in Canberra.

As Minister for Labour and National Service, Holt was responsible for the introduction of conscription to provide Australian troops for the war in Korea from 1950 to 1953. Registration remained compulsory for men over 18 until 1959. Holt also established a notable rapport with Albert Monk, the President of the Australian Council of Trade Unions. Under Holt, the Department of Labour and National Service expanded to 6 divisions, including Training, Planning and Research, by 1953.

In March 1951, the Governor-General granted Menzies’ request for a double dissolution after the Senate failed to pass the government’s banking legislation. At the election on 28 April, the government was returned with a reduced majority in the House, and lacking control of the Senate.

Like most parliamentarians, Holt’s life in Canberra was punctuated with many social events. In June 1951, Holt gave one of the toasts at the Jubilee Banquet in Canberra, the others were given by the Prime Minister and 3 former prime ministers, Ben Chifley, Arthur Fadden and Earle Page. The following night the Holts also attended the gala Jubilee Ball in Kings Hall, Parliament House. The ball came to a sombre halt when Menzies was notified that Ben Chifley had just died.

In December 1951, Holt was elected chairman of the Council of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association at a meeting in Colombo. He then made a 4-day visit to Singapore, where he was briefed on the ‘Communist terrorist problem’. This was Holt’s first official visit to Southeast Asia, and was the beginning of an annual grand tour abroad, usually in the parliamentary winter recess, and always accompanied by Zara Holt.

The first tour, from July to October 1952, included many stops in Europe and North America. The tour began with an audience with the Pope and migration meetings in Rome, then visits to Malta, Geneva and Venice. In London, Holt negotiated with the Anglo-Iranian Company (later British Petroleum) over a proposal to build an oil refinery at Kwinana on Cockburn Sound, Western Australia. The Holts travelled back to Geneva, then to Copenhagen, Stockholm, Dusseldorf, Berlin, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, and The Hague, then to Belfast and back to London. From there they flew to Ottawa for the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association meeting, and visited New York, Washington, Chicago and San Francisco before flying back to Australia.

From May 1953, just after the half-Senate elections, until September, the Holts were again overseas. This trip started in London where they attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and Holt was made a Privy Councillor. A month after their return, the Holts were hosts to new United States Vice-President Richard Nixon and Patricia Nixon. As a member of the Olympics coordination committee for the 1956 Games in Melbourne, Holt ensured that the Nixons toured the Olympic site during their visit.

The years 1954 and 1955 were eventful in Australian politics. 6 weeks after the Royal visit in February-March 1954, Soviet embassy officials Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov defected. Robert Menzies called a federal election for 29 May 1954, but Labor gained 5 seats from the Liberals. In the ensuing months, however, bitter divisions in the Labor Party grew. In 1955, the party split, with anti-Communist ‘Groupers’ leaving the party. Robert Menzies secured an early dissolution of parliament on the grounds of bringing together the elections for both Houses. 3 weeks before the 10 December election, Holt was injured and his driver killed in a car accident at North Sydney, after a Newcastle election meeting.

A month after his government was returned with an increased majority, Robert Menzies divided his enlarged ministry of 22 into an inner Cabinet of 12 and an outer group of 10, who attended if required. Holt remained in the inner Cabinet as Minister for Immigration and for Labour and National Service.

In the mid-1950s, Holt presided over significant change in Australian immigration policy – it was the portfolio he said he found most satisfying. By 1954, Australia had received 250,000 migrants from postwar Europe, 50,000 of these from the Netherlands alone. The following year, 1 million postwar migrants had arrived from all countries including Britain. In August 1956, Australia’s immigration intake was cut for the first time in the postwar years, but Holt agreed to allow 10,000 refugees from Hungary to migrate to Australia after the Soviet Union violently repressed the uprising there.

On 26 September 1956, Holt succeeded Eric Harrison as deputy leader of the Liberal Party and leader of government business in the House of Representatives. When Robert Menzies reshuffled his ministry the next month, he transferred Immigration from Holt to Athol Townley. In his continuing role as Minister for Labour and National Service, Holt worked closely with Deputy Opposition Leader Arthur Calwell.

Treasurer 1958–66

In March 1958, John McEwen succeeded Arthur Fadden as leader of the Country Party. At the November federal election, Fadden retired from parliament. When the Menzies–McEwen coalition was returned with a substantial majority, Holt replaced Fadden as Treasurer in the ministry sworn in on 10 December 1958, ending the custom of a Country Party member holding the Treasury portfolio that had started with Earle Page in 1923.

In April 1959, Holt was the minister responsible for the establishment of the Reserve Bank, to take over the central banking function from the Commonwealth Bank. Holt had worked with the head of the Treasury Department, Roland Wilson, when he was first Minister for Labour and National Service and had developed his usual easy working relationship. Under Holt, Wilson implemented relaxation of controls on interest rates and on trading in government securities. Holt’s first budget, brought down on 11 August 1959, was one to please both the voters and the Treasury. It provided a cut in income tax and an increase in pensions, but brought rises as well in telephone and postage costs, and heavier charges under the pharmaceutical benefits scheme.

For the next 6 years, the budget cycle structured work, family and social life for the Holts. The year Holt became Treasurer they had built a comfortable beach house at Portsea, Victoria, where Zara Holt’s parents had retired. In 1960, they bought a second seaside retreat, at Bingil Bay in north Queensland. Each winter they spent Holt’s birthday fortnight at the Bingil Bay hideaway where he worked on his budget speech. They flew south to Canberra for parliament’s budget session, then spent the next months travelling around the world on a round of Commonwealth finance ministers conferences and financial meetings.

Arranged around these events were discussions with bankers in various of the global ‘capital’ cities, such as London, New York and Zurich. In 1959, the Holts were away for 7 weeks, with World Bank meetings in Washington added to their itinerary. They returned to Australia in time for Holt to lead the Australian delegation to the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association conference in Canberra in November 1959.

By early February 1960, Cabinet was reviewing a deteriorating economic situation and considering ways to curb inflation. Holt’s second budget was delivered in parliament on 16 August 1960. It was a moderate rather than a firm response to falling wool prices, drought and rising inflation. 2 months later, on his return from the winter trip overseas, Holt introduced a supplementary budget. Dubbed ‘Holt’s Jolt’, this measure raised interest rates, tightened credit, and increased the sales tax on motor vehicles.

At a by-election the next month, the Coalition fared badly and, on 21 February 1961, Cabinet overturned the increase in car sales tax. On a ‘Meet the Press’ television appearance a week later, Holt declared himself unmoved by his Cabinet colleagues’ apparent censure.

Despite a relaxation of Holt’s unpopular ‘credit squeeze’ in June, the December 1961 election left the Coalition with a majority of only 1 seat in the House of Representatives. After visits to Athens, London and New York in 1962, Holt spoke at World Bank meetings in Washington in favour of global trading opportunities, rather than foreign aid for developing countries.

On their visits to the United States in 1962 and 1963, the Holts’ schedule included meetings with President John Kennedy among other members of the US government. After Kennedy’s assassination on 22 November 1963, Lyndon Johnson succeeded him and was resoundingly returned at the 1964 elections.

In April 1965, after Johnson had announced an imposition of ‘arbitrary and unilateral’ restrictions on overseas capital, Holt went to the United States for special economic and trade discussions. While Holt was in Washington, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the government’s decision to send combat forces to Vietnam. Holt gratefully observed the immediate effects on his negotiations – doors opened both literally and figuratively.

Holt brought down his last budget on 17 August, the 30th anniversary of his election to parliament. 6 months later, on 20 January 1966, Robert Menzies announced his retirement. Holt was elected party leader by the Liberal parliamentarians, pointing out that he had managed to become Prime Minister without climbing over any ‘dead bodies’. William McMahon succeeded Holt as deputy leader, defeating Paul Hasluck in the ballot.

Sources

- Frame, Tom, The Life and Death of Harold Holt, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005.

- Hancock, Ian, ‘Harold Edward Holt’, in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland, Sydney, 2000.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.