The elation of the 5000 people who farewelled James and Sarah Scullin at Melbourne’s Spencer Street station was matched by the crowd which hailed the train at the Canberra railway terminus the following day, singing ‘See, the Conqu'ring Hero Comes!’.

Labor had its biggest majority yet in the House of Representatives, with 46 of the 75 seats – but were outnumbered in the upper House, with only 7 of the 36 Senate seats. The Scullin government thus had limited legislative effect. The Senate blocked some key measures of the Labor program, including bills to give the Commonwealth greater constitutional powers over industrial relations and trade, and the Central Reserve Bank Bill.

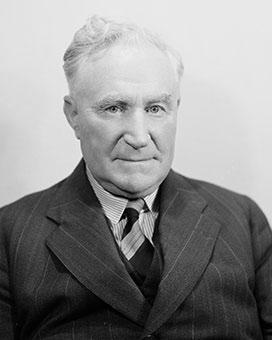

Outgoing Prime Minister Stanley Bruce hands over to James Scullin in the Prime Minister’s office in Parliament House, on 23 October 1929. NAA: A3560, 6122

The Cabinet

Labor had been out of office for thirteen years, and none of the new Cabinet sworn in at Government House late on 22 October 1929 had ministerial experience – not even the Prime Minister. Earlier in the day, Caucus had elected 10 ministers and Scullin had allocated the portfolios.

As Treasurer he chose Ted Theodore, former Premier of Queensland, and Joseph Lyons, former Premier of Tasmania, was Postmaster-General and Minister for Works and Railways. Scullin took the portfolios of External Affairs and Industry, while Frank Brennan became Attorney-General, and Albert Green the Defence Minister. The remaining 5 portfolios were allocated to James Fenton (Trade and Customs), Arthur Blakeley(Home Affairs), Frank Anstey (Health, and Repatriation), and PJ Moloney (Markets and Transport, separated into 2 portfolios in April 1930). Senator John Daly became Vice-President of the Executive Council, and 2 assistant ministers were appointed – Jack Beasley, assisting Scullin in Industry, and Frank Forde, assisting Fenton in Customs.

Depression

When the 12th Commonwealth parliament was opened a month later on 20 November 1929, the new government introduced a program it could not implement once the reality of economic depression unfolded. Scullin immediately ended the licensing system for waterside workers imposed by the Bruce–Page government, but this was not the time for implementing industrial relations reform. The Rothbury miners’ strike in New South Wales was a severe test of the new Labor government, as was the unemployment escalating throughout Australia.

Plummeting export income and consequent worsening of the trade imbalance had been dealt with by the Bruce–Page government by exporting gold reserves. Even before Scullin was sworn in, Robert Gibson, Commonwealth Bank chairman, had sought a meeting to advise the incoming Prime Minister of the effect of this trend given the high level of Australia’s overseas debt. It was not the collapse of the New York stock market in October 1929, but the burden of loan repayments due to London bankers that revealed the stark situation for Australia when parliament resumed in March 1930.

The emergency economic remedies devised by the Scullin government included abandoning the gold standard, ending assisted immigration and increasing import tariffs. To meet the increased cost of urgent social services, the government turned to the Commonwealth Bank (established by the Labor government of Andrew Fisher) for extended credit. When the government brought down its first budget in July 1930, the Treasurer, Ted Theodore, had been forced to resign to face fraud charges in Queensland. Scullin took over the Treasury portfolio.

In August 1930, a Bank of England delegation led by Otto Niemeyer, met with Commonwealth and State leaders at a special conference in Melbourne. The premiers agreed to an economic plan devised by the Niemeyer group and Robert Gibson. Scullin concurred with this plan to balance the budget without additional overseas borrowing by reducing government expenditure and cutting wages. This meant widespread cutbacks, reducing social welfare programs, and a sweeping review of defence policy.

In both defence and foreign policy, the Scullin government contributed little to the nation building of Stanley Bruce, William Hughes or Alfred Deakin. Instead of following recommendations to develop a diplomatic post in Washington, Scullin took the opportunity to save costs when Herbert Brookes resigned his post as Commissioner-General in New York in September 1930.

Outgoing Prime Minister Stanley Bruce had spent an hour of his 2-hour handover to Scullin on 23 October 1929 trying to convince his successor to retain Richard Casey as Liaison Officer in London, and to continue to foster the growth of a Department of External Affairs. External Affairs was then a half-department headed by Walter Henderson within the Prime Minister’s Department, but Alfred Stirling had already been named for a new post in the proposed department. In March 1930, Scullin asked John McLaren, head of the Prime Minister’s Department to report, but by May, he had reduced the establishment at Australia House and Richard Casey resigned to return to Australia.

Applying the principle of equality of economic sacrifice came at some cost to the development of the diplomatic status required for international recognition of Australia as an independent dominion of Britain.

Lang Labor

Soon after the adoption of the Niemeyer–Gibson ‘Melbourne plan’, Scullin left for the Imperial Conference in London, leaving James Edward Fenton acting as Prime Minister and Joseph Lyons acting as Treasurer. Unionists campaigned against the Niemeyer–Gibson agreement and, within Cabinet, Frank Anstey and Arthur Blakeley were vocal critics. Anstey favoured repudiation of the debts. Caucus supported this response, as did others including Jack Lang, who had replaced Thomas Bavin as Premier of New South Wales.

Scullin succeeded in negotiating reduced interest payments for Australia during his 5 months in England, and on his return he also persuaded Caucus to reinstate Ted Theodore as Treasurer. At a second special premiers’ conference in February 1931, conflict with Lang over Scullin’s refusal to allow defaulting on loan repayments erupted.

The following month when Lang supporter Eddie Ward won the federal seat of East Sydney in a by-election, the parliamentary Labor party split when Scullin would not allow Ward to join the Caucus. The 6 ‘Lang Labor’ defectors, led by Jack Beasley, then held the balance of power in the House of Representatives. In New South Wales, Lang led a separate ‘Lang Labor’ party.

The Commonwealth’s bank

Dissension within both Cabinet and Caucus over Scullin’s reappointment of Robert Gibson as Commonwealth Bank chairman, and the wage and welfare cuts introduced under the Niemeyer–Gibson plan, had also reached a crisis in March 1931. When Scullin could not get Cabinet agreement to reduce pension payments, Gibson refused the government credit. The Senate then blocked Theodore’s attempt at a special note issue for social welfare funding – after inviting Gibson to address the House. Scullin then held a third special premiers’ conference where strategies were devised. The premiers’ plan received agreement in the Federal Parliament in June 1931.

An Australian Governor-General

The Depression revealed Australia’s economic dependence on Britain. This was at variance with the independent political status defined for Britain’s 4 dominions at the 1926 Imperial Conference, and enacted in Britain’s Statute of Westminster in 1931. While Scullin was pleading for reduced interest payments from the British government in London in 1930, he was also taking an historic stand by providing an Australian nomination for Governor-General, rather than having the matter arranged through the advice of the British government to the King. Furthermore, the Australian Government put only 1 name before the King, that of the Chief Justice of the High Court, Isaac Isaacs.

Despite the overt disapproval of King George V, Isaacs became the first Australian-born Governor-General. However, for many Australians, this was not triumph, but close to treason. Fears of a socialist plot, or a Jewish one, or a Catholic conspiracy, fed sectarian flames held in check by John Latham, Leader of the Opposition, and fanned furiously by Josiah Symon.

The serpent’s eggs

Diminished parliamentary numbers, not public disapproval, was the chief problem facing the Scullin government in 1931.

When Theodore was reinstated as Treasurer on 29 January, Joseph Lyons and James Edward Fenton resigned from the government. On 4 February 1931, Albert Green was sworn in as replacement Postmaster-General and Minister for Works and Railways. Frank Forde became Fenton’s successor in the Trade and Customs portfolio and Senator John Daly replaced Green as Defence Minister. Then a Cabinet spill toppled Frank Anstey, and Scullin made a third trip to Government House for his brother-in-law, John McNeill, to be sworn in to Anstey’s portfolios of Health and Repatriation. Ben Chifley was brought in to Cabinet to succeed Daly as Minister for Defence, and Senator John Barnes to replace Daly as Vice-President of the Executive Council. This also meant bringing in four new assistant ministers before June 1931, CE Culley, LL Cunningham, Senator John Dooley, and Jack Holloway, the man who had cost Stanley Bruce his seat.

If Anstey accurately described Scullin’s term in office as governing in the ‘serpent’s nest’, then in 1931 all the eggs were hatching.

After their defection from Labor, Lyons and Fenton formed the United Australia Party in a merger with the Nationalists. John Latham stood aside for Lyons who left the government and became Leader of the Opposition. When the Lang Labor group chose to challenge the government and align with the Opposition in passing a ‘no confidence’ motion on 25 November 1931, the government fell. At the election on 19 December, Labor lost all but 14 seats, and the United Australia Party formed the next government in January 1932.

Sources

- Denning, Warren, James Scullin (with introduction by Frank Moorhouse), Black Inc., Melbourne, 2000.

- Edwards, Peter, Prime Ministers and Diplomats: The Making of Australian Foreign Policy, Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Faulkner, John and Stuart McIntyre (eds), True Believers: The Story of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2001.

- Pearce, Sir George, Carpenter to Cabinet: Thirty-seven Years of Parliament, Hutchinson & Co, Melbourne, 1951.

- Robertson, John, JH Scullin: A Political Biography, University of Western Australia Press, Perth, 1975.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Draft of debt conversion agreement and copies of speeches by JH Scullin and EG Theodore, 1931, NAA: A432, 1931/1716

- Scullin ministry, folders of typed copies of Cabinet minutes, 1929–31, NAA: CP450, 1, Bundle 1/4

- Messrs Lyons and Fenton – resignation from Scullin ministry, February 1931, NAA: A5954, 1174/7