John Curtin became the 14th Prime Minister of Australia on 7 October 1941, 8 weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His achievements as Prime Minister were shaped by the war. In a remarkable move, Curtin put United States General Douglas MacArthur in charge of the Australia’s defence forces in the Pacific. He also rejected Britain’s strategy for deploying Australian troops, enabling the successful defence of New Guinea. Although Curtin had been a strong opponent of conscription during World War I, as Prime Minister during World War II he made the decision to send conscripted troops to serve outside Australia, but not outside the Australian region.

New Prime Minister John Curtin, Treasurer Ben Chifley and Minister for Supply Jack Beasley display Australia’s latest defence acquisition, the Bren gun carrier. NAA: M1409, 13, p.2

Curtin inherited a finely balanced parliament. Neither Governor-General Lord Gowrie, nor his fellow parliamentarians believed Curtin would remain Prime Minister for long. Not only was his majority precarious, but Curtin had appeared reluctant to take power in his cooperation with the wartime Coalition government.

Curtin did have doubts about his ability to lead a nation at war, and about assuming power without a clear mandate for Labor. With neither the United Australia Party nor the Country Party able to govern, Curtin became Prime Minister by default rather than choice.

Curtin surprised his colleagues and the Opposition. He proved, like Alfred Deakin, 'a patient and resourceful parliamentary tactician' in an evenly divided parliament. He also rapidly emerged as a strong and decisive chairman of Cabinet and head of government. He drew out a nationwide war effort, and put in place the measures for postwar reconstruction.

Cabinet

When the Curtin ministry was sworn in on 7 October 1941, the first Labor government in a decade took office. Of the 19 ministers, only 4 had portfolio experience, Frank Forde, Ben Chifley, Jack Beasley and Jack Holloway. HV Evatt was Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs. Ben Chifley was Treasurer with Hubert Lazzarini as minister assisting. The portfolios of Social Services and Health were allocated to Jack Holloway, Trade and Customs to Senator Richard Keane, Commerce to William Scully, Postmaster-General to Senator William Ashley, Transport to George Lawson, External Territories to Senator James Fraser, Interior to Senator Joseph Collings and CSIRO to Jack Dedman. 15 portfolios were directly concerned with the war: Defence Coordination (Curtin); Army (Frank Forde); Navy, and also Munitions (Norman Makin); Air, and also Civil Aviation (Arthur Drakeford); Aircraft Production (Senator Donald Cameron); Supply and Development (Jack Beasley); War Organisation and Industry (Jack Dedman); Labour and National Service (Eddie Ward); Information (Senator William Ashley ); Home Security (Hubert Lazzarini); Postwar Reconstruction (Ben Chifley); War Service Homes, and Repatriation (Charles Frost).

Journalist Alan Reid reported Curtin’s determination ‘to make each and every Minister accept in the Cabinet room the responsibility for any action by the Department he represents’. A lot of homework was required for each new minister to ‘know as much about the broad policy of his department as the permanent head and much of the detail’, as Curtin directed.

Although Frank Forde was deputy Prime Minister, Curtin developed a close friendship with Ben Chifley. He also drew on the counsel of James Scullin, whose office in Parliament House was between Curtin’s and Chifley’s.

Preparing for a Pacific war

Both the people and the parliament were looking for a Prime Minister who could draw out Australia’s maximum war effort. 2 prime ministers had already lost power in the finely balanced 16th parliament during 1941. And as Australia faced the increasing possibility of Japan going to war in the Pacific, anxiety about defence readiness became widespread. British war strategy had most of Australia’s best forces committed to the Middle East. Worse, Australia lacked the armaments essential for modern warfare – no modern fighter aircraft, no heavy bombers, no aircraft carriers. And without adequate ground armaments such as tanks, Australia would not have been able to hold out against a major invasion.

Curtin had already been looking for ways to prepare for such a calamity. For years, he had called for the strengthening of Australia’s local defences. He had been a supporter of Archdale Parkhill’s approach as Joseph Lyons’ Defence Minister. Parkhill had developed a bipartisan approach to defence policy, from 1935 when Curtin became Leader of the Opposition. In 1936 and 1937, Parkhill had questioned British assurances on the stability of the Singapore base. When Parkhill lost his seat to Percy Spender in the 1937 election, Curtin had pushed for these initiatives for bipartisan policies, for coastal defence, and for production of defence materiel. And he remained sceptical about relying on Britain to defend Australia.

Readiness to meet the realities of war did not override the opposition to avoidable conflict Curtin had manifested 25 years before. Like others from that time, he believed that an understanding of Japan was essential to avoiding war. In 1940, Adela Pankhurst raised suspicion when she argued for rapprochement after her lengthy visit to Japan in 1939. During 1941, Curtin also attracted criticism when he developed a friendship with Japan’s minister in Australia, Tatsuo Kawai. As well as a formal dinner arranged by Curtin during the Japanese minister’s visit to Perth in 1941, Tatsuo Kawai dined with the Curtins in Cottesloe. He was also a guest at The Lodge after Curtin became Prime Minister, and at the opening of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra on 11 November 1941.

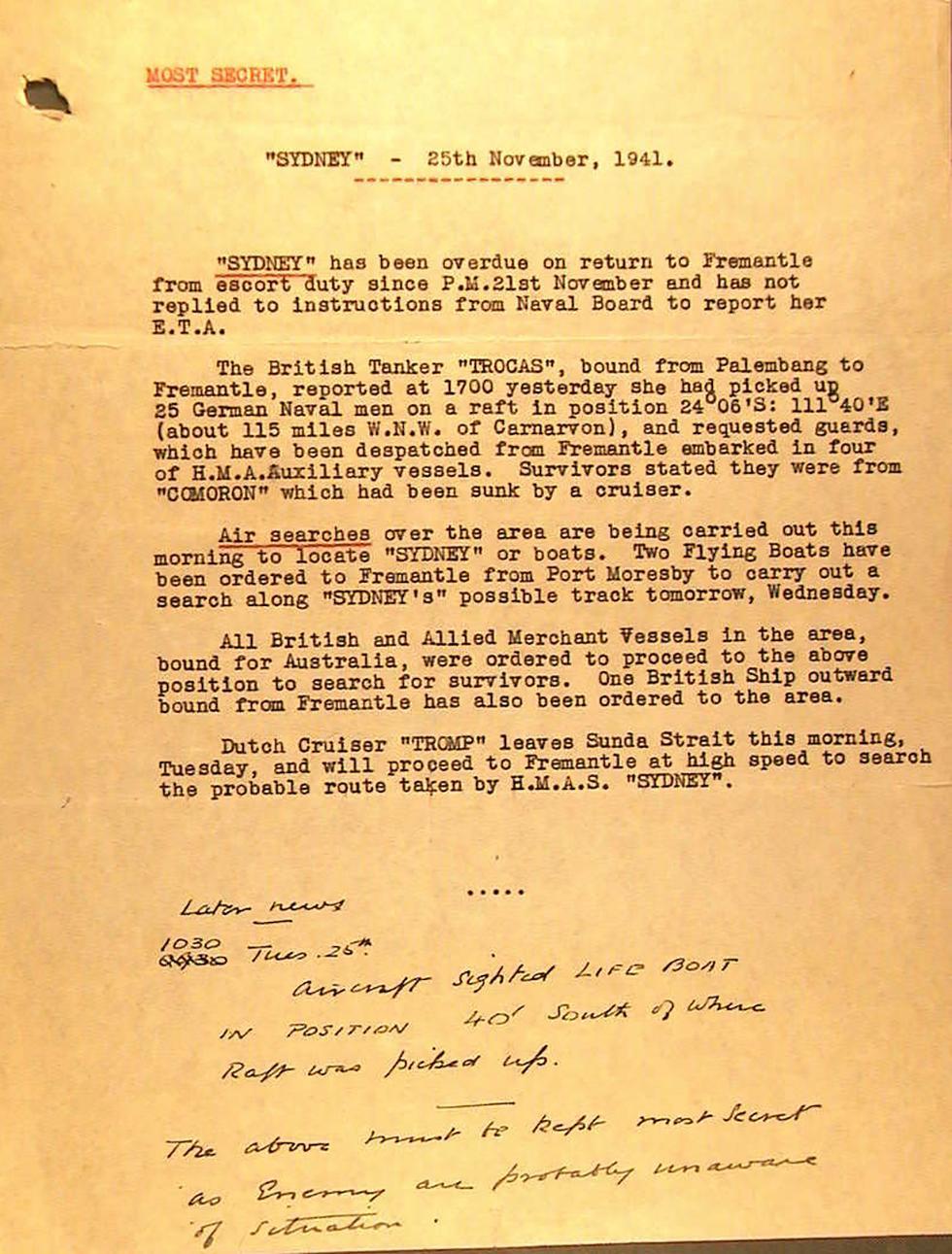

The war with Germany had already reached Australia. Soon after he officiated at the opening of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Curtin received the dreadful news that the cruiser HMAS Sydney was missing off the north-west coast of Australia. On 1 December 1941, he was finally given clearance to announce that HMAS Sydney, along with all of its crew, had been lost after a battle with the German raider HSK Kormoran.

Pearl Harbor

The vain hopes of a peaceful solution to Japanese expansionism collapsed when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US naval base in Hawaii, in the early hours of 8 December 1941 AEST. The previous week, during American–Japanese talks in Washington, Curtin had called a meeting of the War Cabinet in Melbourne on 4 December. Elsie Curtin’s recollection was that one of Tatsuo Kawai’s staff had told Curtin at the conclusion of the Washington talks that ‘the momentum may have gone too far’. She thought this had made Curtin recall the War Cabinet on 5 December to put in place plans for freezing Japanese funds, seizing Japanese vessels in Australian waters, and interning Japanese nationals. Among the thousands of people interned in Australia in the weeks following Pearl Harbor were both Tatsuo Kawai and Adela Pankhurst.

Secret despatch advising the Prime Minister on 25 November that HMAS Sydney had been out of contact for 4 days. NAA: A5954, 2400/21, p.46

The powerful British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse that had arrived in Singapore only days before Pearl Harbor, were sunk soon afterwards, when they steamed out to intercept a Japanese convoy landing the invasion force in Malaya. The ships had been sent by Churchill against the advice of military chiefs and without adequate air support.

The loss of these ships, and US naval losses at Pearl Harbor, meant that Australia could count on little immediate assistance if Japan directed its forces towards Australia. Australia had long regarded the British naval base at Singapore as a crucial defence, with Stanley Bruce arguing for its development at Imperial Conferences in 1923 and 1926. Curtin now appealed to Winston Churchill to send the forces promised in exchange for Australian contributions to the European war. But little more than token forces were forthcoming from Churchill, who was intent on concentrating the imperial forces in the Middle East. Churchill believed that a full-scale invasion of Australia was unlikely, and his 'assurances' nested on a notion of 'imminent' Japanese invasion.

With Churchill’s intentions now clear, and the Japanese army moving south towards Singapore, the threat to Australia was more grave. Curtin wrote a New Year message alerting Australians to the danger. His assertion that Australia now ‘looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom’ first appeared in the press on 27 December 1941. It provoked outrage from some Australians, and greatly angered Churchill because it undermined the then secret Anglo–American strategy of defeating Germany before turning against Japan. It also upset Roosevelt who thought it disloyal. Curtin wanted the Allies to fight the Japanese with the same vigour as they were fighting the Germans and the Italians. After the Soviet–Nazi alliance was ruptured when Hitler’s army invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Curtin also wanted the Russians to join the war against Japan.

Rousing Australians to greater effort for their own defence was difficult at times. There was industrial action on the waterfront and many Australians reacted against the increasing numbers of US troops in Australia, especially in Queensland, where most US camps were established. The ongoing controversy over Communism became more complicated after 1941 when the Soviet Union became an ally and not an enemy. Among leading figures in the Russia–Australia Friendly Society were Labor parliamentarians like Maurice Blackburn, and prominent Labor activists like Jessie Street. Curtin was required to manage recurring conflict between this group and former ‘Langites’ like Sol Rosevear. Even more troublesome was the Minister for Labour Eddie Ward.

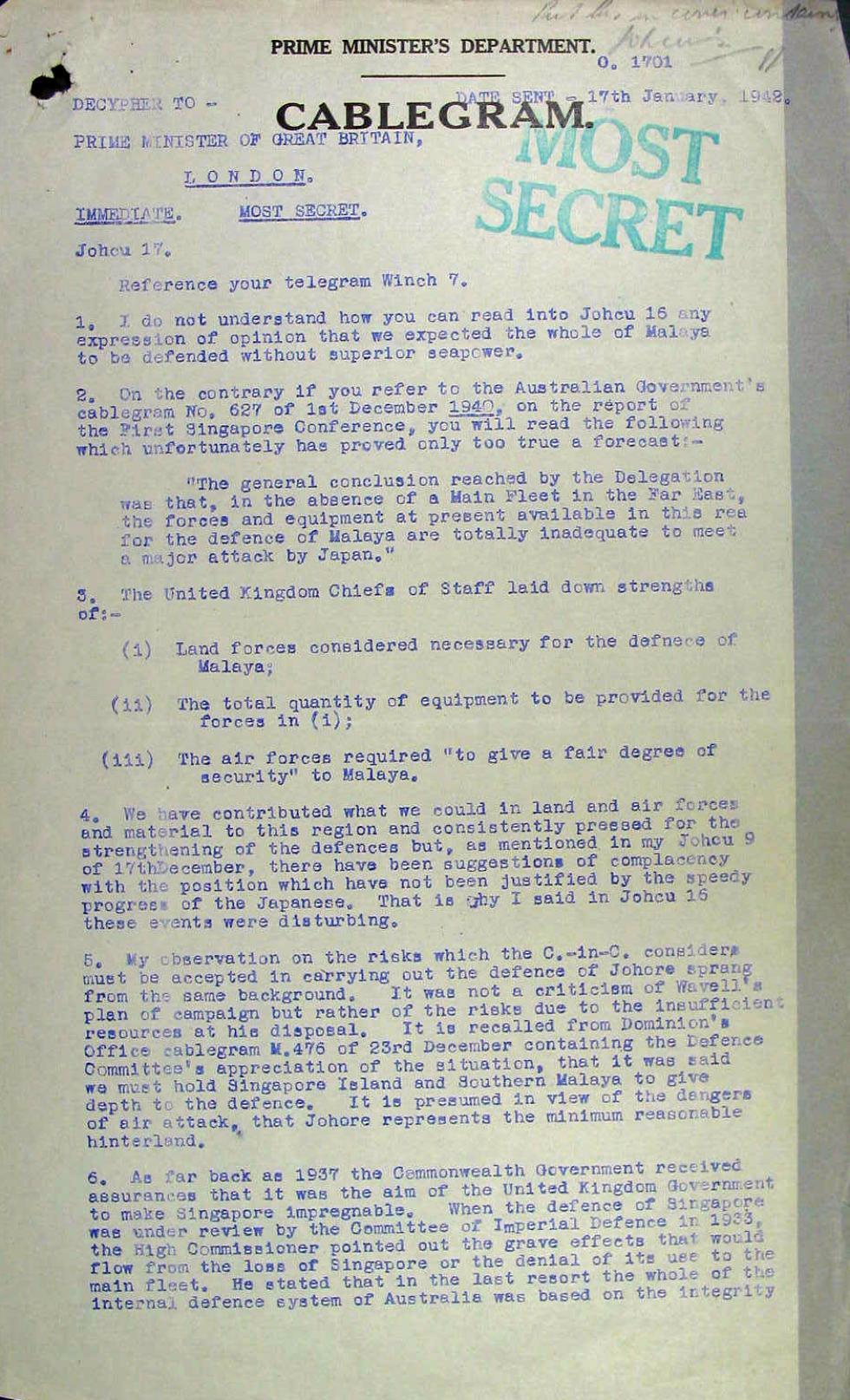

During the Christmas of 1941 and the first weeks of 1942, Curtin called on Churchill to come to the defence of Australia, as promised. On 5 January 1942, he confided to Elsie Curtin, who had left Canberra for Perth the day after Pearl Harbor, the ‘war goes very badly and I have a cable fight with Churchill almost daily’. Aware of the severe stress, colleagues convinced Curtin to take a break with his family and, in late January, he went home to Perth for 2 weeks.

On 17 January 1942 in ‘Johcu 17’ of their coded cablegrams, Curtin challenges Churchill on assurances made to Australia in 1937 about the safety of Singapore and Malaya. NAA: A5954, 581/17, p.27

Fall of Singapore

The successive collapses of the hastily prepared British defences in Malaya shocked the nation. Curtin was back in Canberra when British, Indian and Australian troops made a desperate and disorganised last stand at Singapore before capitulating to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. The vital base was lost, and some 120,000 British, Indians and Australians were captured. Curtin described the fall of Singapore as 'Australia’s Dunkirk' and suggested it would be followed by the ‘battle for Australia'. His prediction seemed fulfilled almost immediately, when the Japanese launched their first air raid on Darwin on 19 February 1942. The bombing in successive raids destroyed much of the town, as well as the ships in its harbour. Curtin told Australians there was ‘no more looking away now. Fate has willed our position in this war’.

Construction of defensive roads and airfields across the isolated and largely unpopulated northern reaches of the continent was now imperative. So were defence installations around the coastline, with barricades on beaches, and demolition strategies in ports and harbours. Curtin established an Allied Works Council under former Labor Treasurer EG (Ted) Theodore, with unprecedented powers to direct workers wherever they were needed.

But more immediately, battle-hardened Australian troops were needed at home to fend off the feared potential invasion. Two of the three Australian divisions in the Middle East were being returned to fight the Japanese, but Churchill wanted them at Singapore or in the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia). When Singapore fell, Churchill pressured Curtin to divert the troopships to Burma, to shore up Rangoon’s crumbling defences. On the urging of his defence advisers Curtin resisted, insisting the troops return to Australia. He did, however, agree to Churchill’s request that 2 brigades go to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). They spent several months on the island, defending the British colony from an invasion that never came.

For the weeks it took the troop convoys to negotiate the Japanese-dominated waters of the Indian Ocean, Curtin was anxious and frequently called on Ray Tracey, his driver, for a late-night game of billiards or just ‘a yarn’. During sleepless nights, Curtin would pace the grounds of The Lodge for hours. After one Saturday parliamentary session Curtin disappeared – he spent hours walking at night at Mt Ainslie. Defence Department head Frederick Shedden meanwhile screened urgent messages at Canberra cinemas, trying to locate the Prime Minister to approve a despatch.

Curtin’s cabled disputes with Churchill resulted in little reinforcement for Australia, but added to Churchill’s resentment at the Prime Minister’s pressing of Australia’s interests.

MacArthur

Australia’s salvation came in the person of General Douglas MacArthur, commander of US forces in the Philippines. General MacArthur was ordered by President Franklin Roosevelt to organise Pacific defence with Australia in March 1942, after the fall of Singapore. Curtin agreed to Australian forces coming under the overall command of MacArthur and passed the responsibility for strategic decision-making onto MacArthur who was titled Supreme Commander of the South West Pacific. From MacArthur’s point of view this was a workable alliance. He told Curtin to 'take care of the rear and I will handle the front'.

Curtin dispatched External Affairs Minister, HV (Bert) Evatt, to Washington and London in 1942 to seek additional commitments of personnel and resources. Evatt was particularly keen to obtain modern aircraft for the Royal Australian Air Force. But little was forthcoming from Churchill, other than a symbolic commitment of 3 Spitfire squadrons, two of them crewed by Australian airmen. However, Evatt did discover that the British and the Americans had secretly agreed to a strategy of fighting Germany first while maintaining only a holding war in the Pacific.

Unfortunately, Evatt also played into Churchill’s hands in enabling RG (Richard) Casey to transfer from his role as Australia’s minister in Washington, to become Britain’s minister to the Middle East. This carried the desired Australian seat on the British War Council but, in practice, Casey would be absent from most meetings. Casey’s move was announced in Britain on 19 March, before he resigned the Washington post. Moreover, it was expressly against Curtin’s wishes, and set off another cablegram battle with Churchill, who had engineered the transfer. Both Evatt and Robert Menzies had long sought the Washington position, but High Court judge Owen Dixon replaced Casey in May 1942.

In May and June 1942, parliament passed legislation establishing a uniform tax scheme. The Commonwealth thus took over the States’ role of collecting income tax. Despite a High Court challenge, this major change became law. Though this was a wartime measure, income tax collection has remained a federal power ever since.

Another major law enacted that year was the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act. This was Australia’s ratification of the 1931 British Act establishing the independence of the dominion parliaments. Ratification had been long delayed by the Lyons government. Ratification was enacted on 9 October 1942, and backdated to the declaration of war with Germany.

The fight for New Guinea

During 1942, US forces in Australia steadily increased in number, but did not exceed Australian forces until 1943. Until then, the country’s defence relied mainly on Australian efforts, reinforced by the occasional intervention of US naval forces from Hawaii.

Although Curtin’s defence advisers predicted that Australia would be invaded by mid-1942, the Japanese had decided against this option, planning first to isolate Australia. This strategy involved a seaborne capture of Port Moresby, the capital of Australia’s Territory of Papua New Guinea. Forewarned by naval intelligence, the US deployed an aircraft carrier force and engaged the Japanese in the battle of the Coral Sea in the first week of May 1942.

Anxious to maintain Australia’s war effort, Curtin called on Australians to ‘sacrifice their peacetime things’. He warned that invasion was ‘a menace capable hourly of becoming an actuality’. After the Japanese navy lost four of their aircraft carriers at the battle of Midway in early June 1942, MacArthur assured Curtin on 11 June that ‘the security of Australia had now been assured’. The fighting, though, was far from over.

With their naval forces effectively defeated, the Japanese called off their planned capture of Port Moresby by sea. Instead they launched a land attack, across the Owen Stanley mountains. Establishing bases on the north coast of New Guinea, the Japanese forces began the assault on Port Moresby. MacArthur was slow to respond to this challenge, not believing a successful attack across the forbidding terrain was likely. But the Japanese soldiers captured Kokoda, and pushed on towards Port Moresby. At MacArthur’s urging, Curtin ordered the Australian army commander, General Thomas Blamey, to go to Port Moresby to take personal charge of its defence. Blamey arrived at Port Moresby in late September, in the middle of an eight-week Australian offensive on the Kokoda Trail. But the Japanese defeat at Milne Bay made their advance impossible, and the victory at Kokoda on 2 November 1942 marked the turning point in the southward sweep of the Japanese offensive. The Japanese commanders turned their attention to the Solomon Islands base of Guadalcanal.

Curtin was congratulated on his first anniversary as Prime Minister by US Ambassador Nelson Johnson, who gave him much of the credit for lifting the ‘black blanket of despair’ over Australia. Johnson declared that Curtin’s ‘earnestness’, ‘honesty of purpose’ and ‘innate integrity’ had allowed him to hold sway over both parliament and people. Sydney’s Sunday Telegraph claimed that the government’s balance sheet ‘showed a handsome credit – attributed in large measure to John Curtin personally’.

Curtin was still battling with Churchill, attempting to bring the last remaining Australian force in the Middle East. It took months of cabled arguments before the troops finally returned early in 1943.

The war at home

Curtin had to fight some of his own colleagues when he bowed to pressure from the United States and his conservative opponents and introduced conscription for overseas service within Australia’s immediate region. Although Curtin had bitterly opposed conscription during the first world war, as head of government of a nation at war, he conceded that conscription was necessary to ensure the adequate defence of Australia and its overseas territories. To his critics in the party, his position seemed to contradict everything that Labor stood for. Curtin wept when radical Labor parliamentarian Eddie Ward charged Curtin with ‘putting young men into the slaughterhouse, although thirty years ago you wouldn’t go into it yourself’. But he pushed his proposal through a special Labor conference in January 1943.

Curtin was rewarded at the federal election in August 1943. Still managing a minority government, he asked for a popular mandate for his leadership and his government’s plans for postwar reconstruction. Personnel devoted to the war effort had doubled since October 1941, and he promised policies for full employment, assisted immigration and improvements in social security. United Australia Party leader, 79-year-old William Hughes, alleged Labor was using the war to socialise the country. Curtin made a firm statement rejecting this allegation. Against his divided opponents, Curtin won a resounding victory. Labor won control of both Houses, and Curtin won a massive majority in his seat of Fremantle.

The only Labor newcomer to the Cabinet was Arthur Calwell. Curtin appointed him as Minister for Information, and moved the troublesome Eddie Ward from Labour and National Service to the Territories portfolio. The major task confronting the new government was balancing the competing needs of the civilian economy with the ongoing needs of the war. The delivery of practical assistance to the United States in the Pacific continued and the British government finally proposed basing forces in Australia. Meanwhile, the needs of postwar reconstruction had started to make demands on manpower.

Not all Curtin’s decisions were sound. MacArthur had promised to take Australian forces forward with him to the Philippines, but instead left them the more mundane task of containing Japanese on various islands bypassed by the US advance. Curtin agreed to Australian forces launching costly offensives to ensure Australia was seen to play a strong role in the final stages of the war.

Planning for peace

Curtin’s approach to postwar planning was aimed at Australia having a predominant role in its own region. This included an influence in former European colonies in the Pacific. The Australian–New Zealand declaration in January 1944, seeking to contain US control to territory north of the equator, caused considerable offence in both Washington and London.

Curtin also sought to restore Australia’s place in the British empire. He mollified London in the matter of a replacement Governor-General when Lord Gowrie retired. To the surprise of the British government, and the displeasure of the Labor Party, Curtin nominated the Duke of Gloucester. Since James Scullin’s celebrated success in nominating the first Australian, Sir Isaac Isaacs, it had been party policy that the post should be filled by an Australian. In deference to the policy, Curtin had made the gesture of first asking Scullin to accept nomination.

In April 1944, Curtin held talks on postwar planning with US President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The Curtins sailed across the Pacific in SS Lurline, a blacked-out troopship carrying several hundred Australian ‘war brides’ to the United States. Curtin himself was occupied for the first few days on board tenderly caring for his wife, suffering an acute reaction to a smallpox vaccination. In San Francisco, the Curtins were met by Owen Dixon, who accompanied them on the train across North America to Washington’s Union Station. US Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Lady Dixon escorted them to Blair House, the residence for official guests near the White House.

From there they flew with Eleanor Roosevelt to Warm Springs, South Carolina, where the ailing President was taking a summer break. The 2 men held the meetings at which Roosevelt approved Curtin’s proposal to redirect manpower towards postwar reconstruction.

Despite Elsie Curtin’s entreaties, Curtin refused her plans to go to England with him, apparently because he did not want to risk both their lives aboard a flying-boat over the Atlantic. Interviewed by reporters, Elsie made no secret of her unhappiness at being ‘dumped’ in Washington, where she stayed at the Australian Embassy with the Dixons.

Landing in England, Curtin immediately advanced postwar Australia’s claims, announcing he spoke for the ‘seven million Britishers’ there. In a radio broadcast, he described Australia as ‘the bastion of British institutions, the British way of life and the system of democratic government in the Southern World’. These repeated affirmations went some way to allaying the antagonism of British political and military leaders, and perhaps encouraging investors and trade officials. As in the United States, Curtin succeeded in obtaining agreement to Australia’s manpower plans. With British and American agreement, Australia was ready to move from a military to a postwar economy, and from prewar imperial relations to postwar diplomacy.

Less successful was Curtin’s proposal to establish a secretariat to coordinate the empire’s foreign policy. He proposed this body would move between London and the dominion capitals. But he faced overt opposition from Canada and South Africa, as well as more surreptitious opposition from Churchill.

When the Curtins were reunited in Canada at the end of May, Elsie Curtin recalled that John Curtin was ‘tired and disinclined to talk at length about his time in England’. After a few days break, the couple returned to Washington for further official meetings. They also managed a brief visit to New York, where they saw the new Broadway musical, Oklahoma!

Braving the perils of crossing the war-torn Pacific on USS Matsonia, the Curtins arrived back in Australia on 26 June 1944. Curtin assured Australians that he had ‘not seen any other people or any other country better than my own’. He was immediately immersed in the campaign for the referendum to extend federal government power over employment, monopolies, Aboriginal people, health and railway gauges. Combined in a single question, the proposal for constitutional change was decisively rejected by Australian voters. At the same time, Curtin faced stubborn industrial problems on the coalfields. The workers resisted the Labor Prime Minister’s entreaties to return to work.

Curtin’s exhaustion after the overseas trip persisted. In August and September, he complained to friends of ‘feeling flat and sad and over-burdened’ and being ‘very tired after a few hours concentration’. He was able only occasionally to return to his Cottesloe home. There, ensconced in his lounge chair with its specially designed pull-out trays for his tea cup and ash tray, Curtin would read poetry while Elsie played the piano. On 3 November 1944, after one of his rare breaks at home, Curtin suffered a major heart attack in Melbourne on the long train journey back to Canberra. When he was strong enough, he was driven back to Canberra to complete his recovery. On 8 January 1945, he celebrated his 60th birthday at The Lodge.

Although he returned to parliament in February, Curtin was by no means back to normal. Robert Menzies now led a regenerated Opposition, united as the Liberal Party, and ready for rigorous debate. Not only was Curtin forced to excuse himself from parliamentary question time, he was unable to concentrate on the work demanded by the avalanche of Bills being prepared for the coming peace.

Curtin’s exhortation to Frank Anstey in 1934 – that they ‘must go on to the end and not yield while life is left to us’ – he now applied to himself. On 18 April 1945, he moved the parliament’s motion of condolence on the death of President Franklin Roosevelt. Soon after, severe lung congestion forced him back into hospital. Deputy Prime Minister Frank Forde was in San Francisco and Ben Chifley was acting Prime Minister. It fell to Chifley to announce the end of the war in Europe on 9 May 1945.

Curtin was released from hospital on 22 May. That day, he was driven back to The Lodge, and he and Elsie Curtin strolled in the garden together for photographers. They then walked back into The Lodge together for the last time. Inside, Ray Tracey waited with a stretcher to carry Curtin up the staircase to the prime ministerial bedroom on the first floor.

John Curtin died there, on 5 July 1945, just 6 weeks before the end of the war in the Pacific.

Sources

- Curtin, Elsie, 'The Curtin story: prelude to war', Woman, 26 March 1951.

- Day, David, John Curtin: A Life, Harper Collins, Sydney, 1999.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Sydney–Kormoran action signals etc, 1941–1945, NAA: B6121, 165P

- HMAS Sydney 1941, NAA: A5954, 2400/21

- Exchange of Cablegrams between Mr Churchill and Mr Curtin, 1941–1942, NAA: A5954, 581/17