On this page

- Early years

- Soldier and settler

- Member of parliament 1934

- Minister for the Interior 1937–39

- Minister for External Affairs 1940

- Minister for Air and Civil Aviation 1940–41

- In Opposition 1941–49

- Minister for Commerce and Agriculture 1949–56

- Minister for Trade 1956–63

- Minister for Trade and Industry 1963–71

- McEwen vs McMahon

- Sources

- From the National Archives of Australia collection

John McEwen was a Victorian soldier-settler who built his small allotment into a large and profitable farm. He was a member of the Country Party from its formative years and became a parliamentarian in 1934.

He won the deputy leadership of the parliamentary Country Party in 1943 and the leadership in 1962. As deputy Prime Minister from 1958, McEwen was acting Prime Minister many times. McEwen was a minister in the Cabinets of five heads of government. He was Minister for the Interior (1937–39) in the governments of Joseph Lyons and Earle Page, Minister for External Affairs (1940) in Robert Menzies’ government, and Minister for Air and Civil Aviation (1940–41) in Menzies’ and Arthur Fadden’s governments.

Acting Prime Minister John McEwen chairs a Cabinet meeting in June 1965. From left are Billy Snedden, David Fairbairn, Alan Hulme, Allan Fairhall, Charles Adermann, John McEwen, Harold Holt, William McMahon, Senator Shane Paltridge, Gordon Freeth and Charles Barnes. NAA: A1200, L51372

McEwen was a minister for the whole of Menzies’ second term as Prime Minister from 1949 to 1966, serving as Minister for Commerce and Agriculture (1949–56), Minister for Trade (1956–63) and Minister for Trade and Industry (1963–66). He was also Minister for Trade and Industry (1966–67) in Harold Holt’s government, retaining the portfolio when he succeeded Holt as Prime Minister, and from 1968 to 1971 in the government of John Gorton.

Early years

McEwen was born on 29 March 1900 at Chiltern in Victoria, to pharmacist David McEwen and Amy (Porter) McEwen. His mother died after the birth of their second child in 1901, and his father died in 1907. McEwen and his younger sister were raised by their grandmother, Ellen Porter, who ran a boarding house. They lived first at Wangaratta and then moved to Dandenong in 1912.

At the age of 13, McEwen left school and helped support the family, working at local wholesale pharmaceutical supplier Rocke, Tompsitt & Co. In 1914, the family moved to the Melbourne suburb of Balwyn, where McEwen studied at night school. After 2 years of classes at Hassett’s Business College in Chapel Street, Prahran, he qualified for entry to the Commonwealth Public Service. At the age of 16, he started work at the Crown Solicitor’s Office in Melbourne, under Frederick Whitlam, the father of Gough Whitlam.

Soldier and settler

McEwen had hoped to enrol at the Royal Military College at Duntroon in Canberra, but instead applied for enlistment in the 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF) when he turned 18. He was called up on 9 August 1918 and was in camp awaiting embarkation for France when the Armistice was declared on 11 November. After his discharge, he went to work as a farmhand, but his enlistment qualified him for a loan to buy a farm under the ‘soldier-settler’ scheme. He applied for a 35-hectare block at Tongala in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley. To raise capital, he took labouring jobs, including one on the Melbourne wharves.

In 1919, McEwen joined the Victorian Farmers Union, one of the most influential of the primary producers groups that founded the Country Party the following year. On 21 September 1921, McEwen married Anne McLeod at Ballavoca, Tongala.

With hard work and frugal living – McEwen was known locally as ‘secondhand Jack’ – they added to their original farm holding. In 1924, the couple sold their 1200ha dairy farm for £1000 to buy a larger property they named ‘Chilgala’. They developed it first as a sheep station and later changed to beef cattle. The McEwens were both active in the local community and in the broader issues of rural politics. In 1923–24, McEwen was the first chairman of the local Stanhope Dairy Cooperative.

In 1932, McEwen stood unsuccessfully as Country Party candidate for the seat of Waranga in the Victorian parliament. The state party then endorsed him for the federal seat of Echuca. Country Party parliamentary leader Earle Page was then in dispute with the Victorian Country Party, and at the 1934 federal election Page campaigned for an ‘Independent Country Party’ candidate against McEwen.

McEwen won the electorate nonetheless. When he took his seat in the 14th parliament, he joined the parliamentary Country Party led by Page, and was thus also in dispute with his own state party.

Member of parliament 1934

When Joseph Lyons won government in 1932, the United Australia Party was able to govern alone. Lyons attempted to continue this in the 14th parliament. On 23 October 1934, the first sitting day, the Country Party defeated the government’s motion to adjourn until the day after the Melbourne Cup. The Duke of Gloucester was visiting Australia for Victoria’s centenary and Cup week in Melbourne was a special event – much to the inconvenience of parliamentarians sitting in the new Parliament House in Canberra. Lyons immediately responded to the Country Party’s demonstration of the government’s reliance on their numbers, and negotiated a coalition government.

On 9 November a new Cabinet was sworn in, including 4 Country Party members – Earle Page as Minister for Commerce, Thomas Paterson as Minister for the Interior, and Harold Thorby and James Hunter as ministers without portfolio. Country Party leader Earle Page resumed the role of deputy Prime Minister he had held from 1923 to 1929 under Prime Minister Stanley Bruce. Like McEwen, Robert Menzies was first elected to the federal parliament in 1934. He became deputy leader of the United Australia Party in 1935, but the Lyons–Page coalition arrangement prevented Menzies becoming deputy Prime Minister.

The coalition arrangement meant that McEwen was a government backbencher when he made his first speech to the parliament on 15 November 1934. He spoke on the issues at the core of Country Party politics – primary industry, commerce, trade and banking. He also covered employment and defence, the two areas of greatest concern as Australia moved out of the depression years to face the possibility of new conflict in Europe.

In 1935 and 1936, McEwen was a member of the parliament’s Bankruptcy Legislation Committee, and spoke on a proposal for a royal commission into the monetary and banking system.

At the federal election in October 1937, McEwen was returned for the electoral division of Indi, his Echuca seat having been abolished in 1937. The Lyons–Page coalition government remained in office, but Lyons’ hold on the leadership of his own party had become uncertain. Page remained leader of the Country Party and McEwen stood against Harold Thorby for the deputy leadership. Thorby, considered ‘Page’s man’, won the deputy leadership by 1 vote.

Minister for the Interior 1937–39

The coalition ministry was reshuffled after the election, and 5 Country Party ministers were sworn in on 29 November 1937. Page retained the Commerce portfolio and replaced William Hughes as Minister for Health. Harold Thorby replaced the United Australia Party’s Archdale Parkhill as Minister for Defence, and Victor Thompson and Archie Cameron became ministers without portfolio. McEwen replaced Thomas Paterson as Minister for the Interior, with responsibility for Commonwealth public works, railways, immigration, territories, electoral administration, mining and oil exploration. In 1938 McEwen made a 6-week ‘safari’ through the Northern Territory which, with the Federal Capital Territory, was included in his portfolio.

The Victorian Country Party remained at odds with its federal leadership, and had ruled that no member could join a coalition government. McEwen was expelled by his party at a tense branch meeting at Benalla in Victoria on 28 January 1938 and was not permitted to speak during the expulsion debate. A branch member not constrained from contributing to the debate, however, was Anne McEwen. At the annual meeting of the state party on 29 March 1938, McEwen’s expulsion was confirmed and remained in force for 5 years.

The Country Party had its first experience of holding the top post formally when Earle Page became ‘caretaker’ Prime Minister after the death of Joseph Lyons on 7 April 1939. On 26 April, after Robert Menzies was elected leader of the United Australia Party, Page refused to serve in coalition with him and all 5 Country Party ministers went with him. Menzies formed a ministry composed only of United Australia Party members.

Page’s stinging attack on Menzies in parliament had undermined his leadership of his own party and on 13 September 1939 he resigned. McEwen contested the leadership against Archie Cameron, losing by 2 votes. Described as a stubborn and even belligerent man, Cameron was an unlikely leader. In 1938, he had become the first minister suspended from the federal parliament for his obstinate refusal to obey the Speaker’s ruling to withdraw his rural, but hardly rude, reference to Independent Alex Wilson as a ‘clean-skin’. Cameron also attacked parliamentarians who had supported John Curtin’s Bill allowing for conscientious objectors to be reserved from combat roles. Among them were members of his own party, including John McEwen.

Minister for External Affairs 1940

After Richard Casey’s seat of Corio was lost to Labor in a by-election in March 1940, Robert Menzies and Archie Cameron negotiated a coalition which would include five Country Party ministers, but exclude Earle Page. On 14 March 1940, the new Country Party ministers were sworn in – McEwen as Minister for External Affairs, Archie Cameron as Minister for Commerce and Minister for the Navy, Harold Thorby as Postmaster-General and Minister for Health, and Horace Nock and Arthur Fadden as ministers without portfolio. Five months later, after 3 of Menzies’ ministers were killed when their aeroplane crashed near Canberra, Arthur Fadden became Minister for Air and Minister for Civil Aviation.

Both coalition parties lost seats to Labor at the federal election in September 1940, and in October, Archie Cameron resigned as Country Party leader. Earle Page and John McEwen both stood for the leadership and were tied when the votes were counted. To resolve the deadlock temporarily, deputy leader Arthur Fadden was made acting leader.

Minister for Air and Civil Aviation 1940–41

The Menzies–Fadden coalition ministry included 5 Country Party ministers. On 28 October 1940 Arthur Fadden was sworn in as Treasurer, John McEwen as Minister for Air and Minister for Civil Aviation, Earle Page as Minister for Commerce, and HL Anthony and Joseph Abbott as ministers without portfolio. On 26 June 1941, Anthony became Minister for Transport and Abbott Minister for Home Security – giving the Country Party 2 of the 5 new wartime portfolios established by Menzies.

The War Cabinet had met for the first time on 27 September 1939, but in 1940 the government established an all-party Advisory War Council under the National Security regulations to involve the Opposition and promote national unity for the war effort. The members were Robert Menzies, William Hughes, Percy Spender and Arthur Fadden from the coalition, and John Curtin, Frank Forde, Jack Beasley and Norman Makin from the Labor Opposition. As Minister for Air, McEwen became a member of the Advisory War Council and attended his first meeting on 7 November 1940.

McEwen was Minister for Air from October 1940 to October 1941. During this time, Australia played a major role in the Empire Air Training Scheme and the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force was established. Minutes of the Advisory War Council show that credit for both achievements belonged largely to Chief of Staff for the Air Force, Charles Burnett. McEwen and Norman Makin were strong opponents of the enlistment of women and the Auxiliary was only established through Burnett’s determined arguments. He insisted that the numbers of telegraphists and radio operators essential to the Air Force could only be achieved if the hundreds of Australian women with these skills could be recruited. The proposal was not approved until 4 February 1941. Despite Norman Makin’s case for equal pay if the proposal went ahead, the Council included the condition that the women would receive two-thirds of the wages of men in the same jobs.

From January to May 1941, Arthur Fadden was acting Prime Minister while Robert Menzies was in London. The Country Party confirmed Fadden as leader on 12 March 1941. When the United Australia Party removed Robert Menzies as leader on 28 August, the coalition parties voted Arthur Fadden to lead the coalition. The Governor-General commissioned Fadden as Prime Minister on 29 August 1941, but Fadden’s term was brief. On 3 October 1941, the 2 Independents, Alex Wilson and Arthur Coles, voted with the Opposition and the government fell.

John Curtin was sworn in on 7 October 1941 – he was Australia’s 14th Prime Minister and the third within 3 months.

In Opposition 1941–49

The Country Party and the United Australia Party remained on the Opposition benches for 8 years. During the war years, Curtin maintained the all-party bodies involved with the war effort and retained United Australia Party and Country Party members on the Advisory War Council. McEwen was also a member of the parliamentary Privileges Committee from 7 March 1944 to 4 December 1947.

After the United Australia Party and the Country Party lost heavily in the 1943 federal election, McEwen was elected deputy leader of the Country Party. When the Curtin War Cabinet discussed the need for a direct report on the situation in New Guinea in addition to General MacArthur's reports, McEwen was considered. So, briefly, was newspaperman Keith Murdoch. On the Advisory War Council, McEwen advocated independent and first-hand reports of the New Guinea situation, and was critical of the northern air defence strategy. Army Chief of Staff SF Rowell recalled the council meetings as intimidating. Not only were there three King’s Counsel (William Hughes, Percy Spender and Robert Menzies), there were others who were a match for Hughes’ sharp tongue and dominating manner. McEwen advised Rowell to give his answers in exactly the tone the questioner used, saying ‘They’ll take it, they’re used to it’.

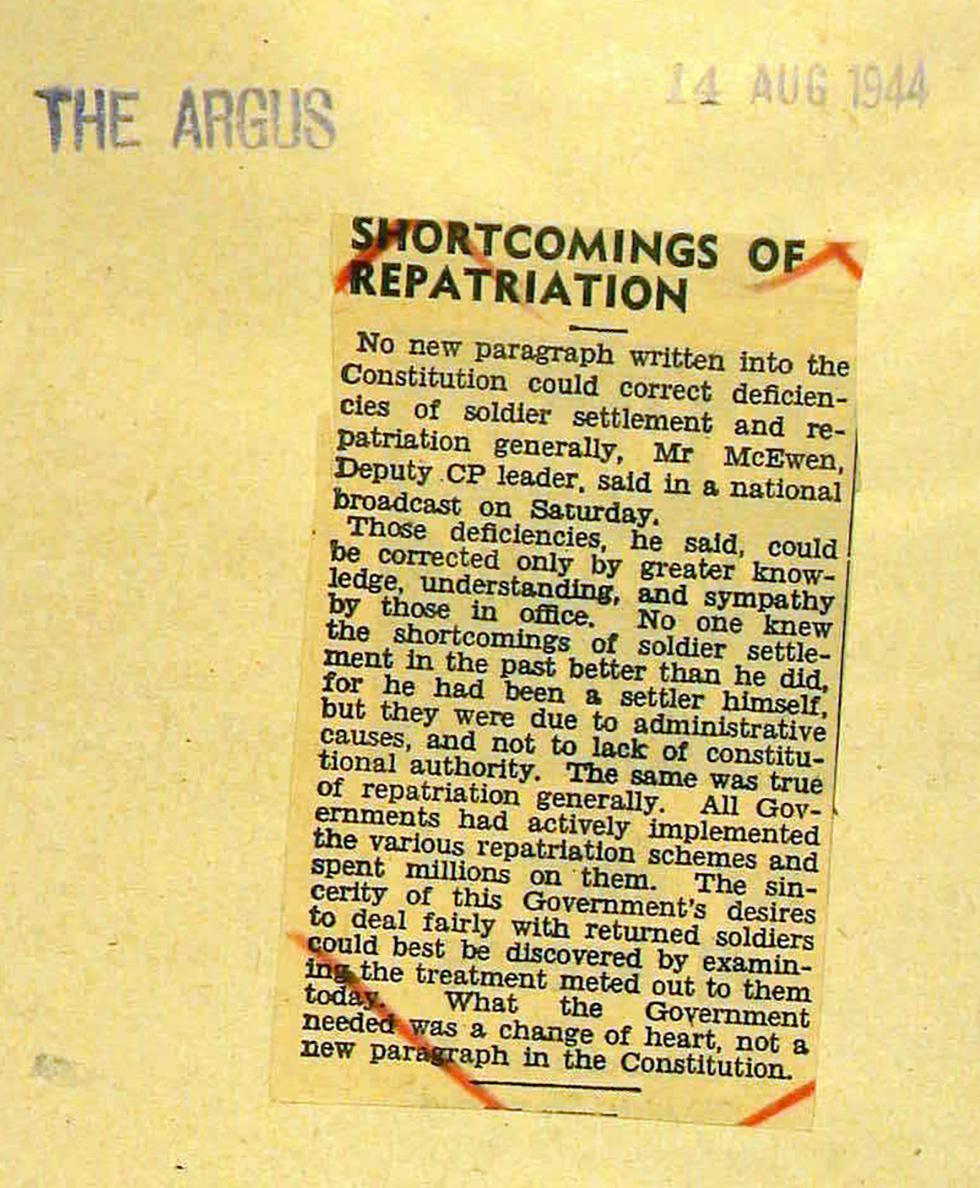

In 1944, the Curtin government held a referendum aimed at extending the federal government’s wartime powers to assist in repatriation and postwar reconstruction programs. McEwen was a leading figure in the ‘No’ campaign, arguing that constitutional change was not a priority.

In a broadcast arguing the 'No' case in the 1944 referendum, former soldier-settler John McEwen said the Curtin government needed 'a change of heart, not a new paragraph in the Constitution' to help returned soldiers best. NAA: A5954, 2215/3, p.4

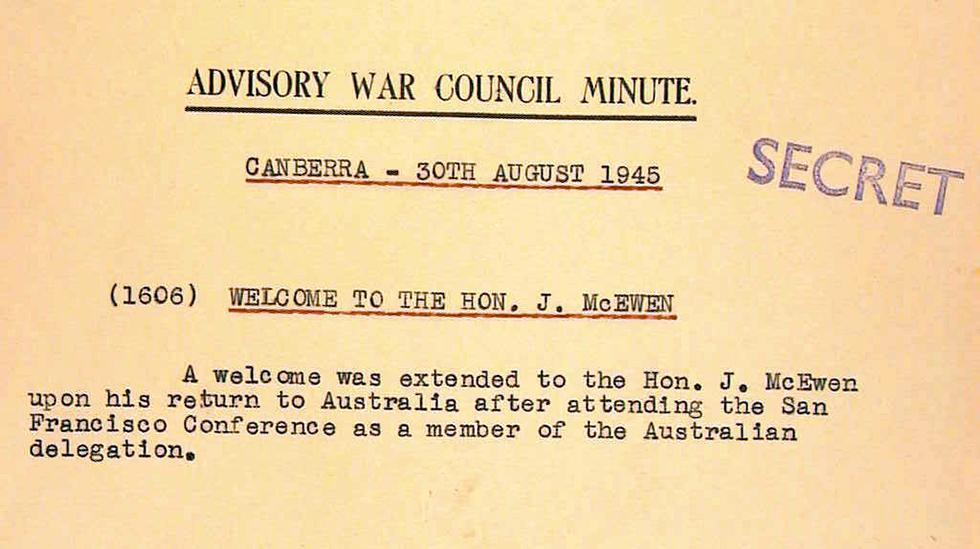

In April 1945, McEwen went to San Francisco as an adviser to the Australian delegation to the conference held to establish the United Nations. The delegation was led by Labor deputy Prime Minister Frank Forde, who became caretaker Prime Minister on his return to Australia after the death of John Curtin on 5 July 1945. McEwen returned to Australia in August, shortly after United States bombers had dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war in the Pacific ended on 15 August.

John McEwen's five years' service was acknowledged at the final meeting of the Advisory War Council on 30 August 1945, two weeks after the end of the war in the Pacific. NAA: A5954, 2215/3, p.3

During the 4 years of the Labor government of Ben Chifley, Fadden and McEwen worked to strengthen support for the Country Party. From the remnants of the United Australia Party, the new Liberal Party was formed and Robert Menzies became leader. At the election on 19 December 1949, a Liberal Party–Country Party coalition was returned with a large majority, and Menzies became Prime Minister. McEwen was now member for Murray, a new division created within his former Indi electorate by the electoral redistribution in 1949.

Minister for Commerce and Agriculture 1949–56

The Menzies–Fadden ministry included 5 Country Party ministers. On 19 December 1949, Arthur Fadden was sworn in as Treasurer, McEwen as Minister for Commerce and Agriculture, Earle Page as Minister for Health, HL Anthony as Postmaster-General and Senator Walter Cooper as Minister for Repatriation.

In October 1950, McEwen travelled to London as Australian representative on an international group investigating wool trading, and the following year he went to Britain for 3 months for meetings relating to export contracts for primary produce and supplies of raw materials for postwar reconstruction. In November and December 1952, he attended the Commonwealth Financial and Economic Council in London. The following year, he was appointed to the Privy Council.

In the federal election in May 1954, McEwen was unopposed in his Murray electorate. At the election in December 1955, the coalition made strong gains in parliament as a result of the Labor Party split after the government’s attempt to ban the Communist Party and the defection of Soviet espionage agents Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov.

Minister for Trade 1956–63

In the new Cabinet sworn in on 11 January 1956, McEwen became Minister for Trade, taking the Commerce responsibilities from his former portfolio to an influential new department. A separate Department of Primary Industry was established and experienced officials moved from the former Agriculture Department to staff it. The new Minister for Primary Industry was Liberal member William McMahon. He was a novice in rural matters and it was assumed that he would follow the lead of the Country Party and in looking after the core interests of their constituents.

In June and July 1956, McEwen attended the conference of Commonwealth Prime Ministers in London. He returned in November that year for negotiations reviewing the Britain–Australia trade agreement. The following June he went to Japan with senior trade officials and negotiated a controversial Australia–Japan trade agreement. The agreement was opposed by manufacturers and trades unions, and by those who continued to see Japan as an enemy – the peace treaty with Japan had been signed only 6 years earlier.

After Arthur Fadden retired as leader of the Country Party, John McEwen was elected his successor on 26 March 1958 and consequently became deputy Prime Minister. From August to October 1958, McEwen visited Malaya and Ceylon, and led the Australian delegation to the Commonwealth Trade and Economic Conference in Montreal, Canada.

Between April 1959 and October 1960, McEwen acted 4 times as Prime Minister while Robert Menzies was overseas, and as Treasurer while Harold Holt was overseas in October 1960. Trade negotiations in the period leading up to Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community were a major concern for the government. One-fifth of Australia’s primary production still went to British markets and the Country Party was keen to negotiate with Britain about the change. In 1962 and 1963, McEwen travelled to the United States, Canada, Britain and Europe for discussions about the effects on Australian trade of Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community.

In July 1962, Leslie Bury, Liberal minister assisting Treasurer Harold Holt, was reported to have said that the impact of Britain joining the European Economic Community would be less damaging than Cabinet had advised parliament. Menzies suspended Bury. Although McEwen was widely thought to have insisted on this, Mary Byrne, his private secretary at the time and later his second wife, recalled Menzies’ phone call that day. The conversation was brief, and the decision made by Menzies before McEwen had even read the story in that day’s papers. In any case, France blocked Britain’s application to join the common market at that time.

After Arthur Fadden’s retirement from parliament in December 1962, the Country Party never again held the Treasury portfolio. As Minister for Trade, McEwen was often in conflict with Treasury on economic policy, but McEwen also differed at times from his rural constituents on trade policy. Rural producers benefited from low tariff barriers on imported agricultural inputs and traditionally favoured free trade. McEwen saw protection of Australian industry as vital, and took this position in meetings on international trade arrangements under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. In July and August 1963, McEwen attended trade talks in Hong Kong, Japan and the Philippines, and secured a renewed Australia–Japan trade agreement.

The Menzies–McEwen Cabinet in the Cabinet Room in 1963, some months before the November election. Seated (left to right): Paul Hasluck, Senator William Spooner, John McEwen, Robert Menzies, Harold Holt, Athol Townley, Charles Adermann, William McMahon. Standing (left to right): Alexander Downer, Reginald Swartz, Senator John Gorton, Hugh Roberton, John Cramer, Allen Fairhall, Senator Norman Henty, Senator Harrie Wade, Garfield Barwick, Hubert Oppermann, David Fairbairn and Senator Shane Paltridge. NAA: A1200, L45498

The coalition had lost ground in the December 1961 election, and both parties responded to this electoral message with a revision of policy and of the policy-making process. In November 1963, they were rewarded with a more comfortable win.

Minister for Trade and Industry 1963–71

In the new Cabinet sworn in on 18 December 1963, McEwen’s portfolio was now titled Trade and Industry, reflecting the establishment of an office of secondary industry in his department. Highly regarded by Robert Menzies, McEwen was in charge of the key areas of commerce and trade for 20 years. This extended period of responsibility meant he developed close and long-term relationships with senior officials like John Crawford and Alan Westerman, as well as an influential network of business and government contacts in Australia and overseas. He went regularly to London for Commonwealth trade meetings, often combined, as in March and April 1964, with international trade and development conferences in Geneva. In June 1964, McEwen attended the inauguration of the Papua and New Guinea House of Assembly in Port Moresby – an important step towards the Territory’s 1975 independence from Australian administration.

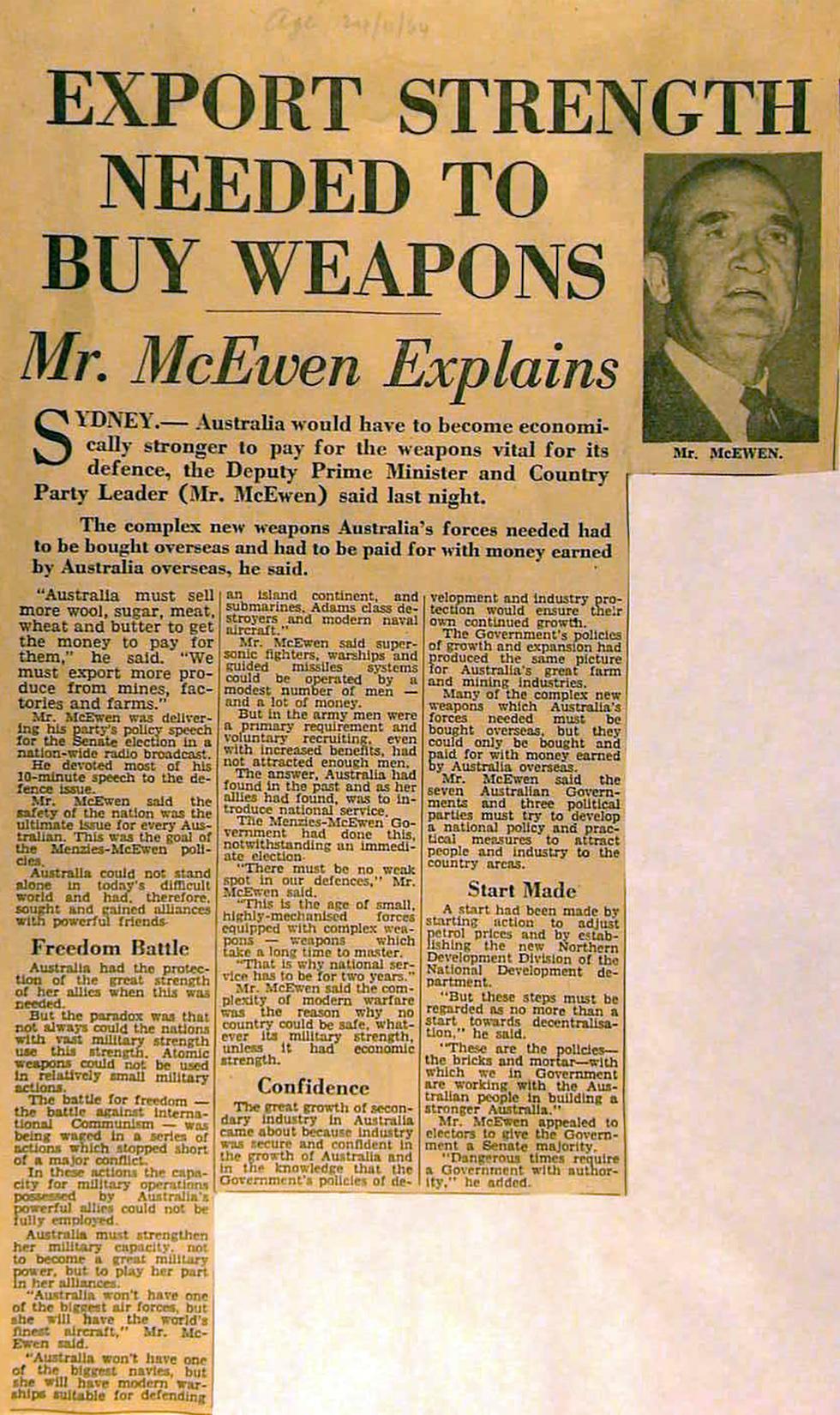

In 1964, an Australian contingent of advisors had been sent to South Vietnam to assist the United States and South Vietnamese military effort in the war against Communist North Vietnam. In November 1964, Cabinet decided to reintroduce conscription, and in April 1965, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced that Australian troops would be sent to Vietnam the following month. In a speech broadcast during the campaign for the Senate election in December 1965, McEwen argued that ‘in the battle for freedom – the battle against Communism – export revenue from mines, factories and farms’ was the necessary basis for a strong and well equipped defence force.

John McEwen's broadcast during the 1964 Senate election campaign, tying trade and development to defence capability, was widely reported as in this article in Melbourne's Age newspaper on 24 November 1964. NAA: A5954, 1118/6, p.27

In June and July 1965, McEwen was both acting Prime Minister and acting Minister for External Affairs when Robert Menzies and Paul Hasluck were overseas. In September and October, McEwen attended an international sugar conference in Geneva.

In January 1966, Prime Minister Robert Menzies resigned after a record 16-year term. The Liberal Party elected Harold Holt the new leader and William McMahon as deputy leader. McMahon also succeeded Holt as Treasurer.

In May and June 1966 McEwen represented Australia in trade talks in London, Poland, Bulgaria and the United States. The following year his talks with British ministers in London in April were followed by the final ‘Kennedy’ round of negotiations on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Four times acting Prime Minister during 1966, John McEwen is here addressing the House of Representatives that year. NAA: A1200, L57225

At the federal election in November 1966, the Holt–McEwen coalition was returned with an increased majority. McEwen was acting Prime Minister in the first week of February 1967, and then went to New Zealand for trade talks. 10 days before the opening of the 26th parliament on 21 February, Anne McEwen died. An invalid confined to a wheelchair for some years, Mrs McEwen had retained her interest in politics from her schooldays and through the 45 years of the McEwens’ marriage.

In May 1967, Britain made a second and now successful bid for entry to the European Economic Community. McEwen went to Brussels, Bonn, Paris and London for discussions, returning to be acting Prime Minister when Holt went overseas at the end of the month. In November and December 1967, McEwen was in Geneva for a world trade ministers’ meeting on the quota proposals of the US Congress. He then attended the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development ministerial council meetings in Paris, and went to Hungary for trade talks.

McEwen’s key preoccupation on his return was the government’s response to Britain’s decision to devalue the pound sterling. He arrived in Sydney on 10 December and was met by the head of the Department of Trade, Alan Westerman, Country Party ministers Doug Anthony and Ian Sinclair, and his press secretary Robert Macklin. Cabinet had decided on 20 November not to follow the British move with a devaluation of the Australian dollar. This would impact on primary producers, particularly those with current export contracts, and was thus a major concern for the Country Party. McEwen’s public statement protested the Cabinet decision and was widely reported.

McEwen vs McMahon

McEwen returned to Canberra on 12 December and Prime Minister Harold Holt, with uncharacteristic firmness, extracted an assurance that his criticism of Cabinet would not recur. But the issue caused the eruption of McEwen’s ongoing enmity with Treasurer and deputy Liberal leader William McMahon. Their bitter rows had long been a source of material – and leaks – for political reporters. Publications like Don Whitingon’s Inside Canberra and Frank Browne’s column ‘Things I hear’ were as avidly read for the latest news by parliamentarians, as well as the public.

2 days before McEwen had returned to Australia, Governor-General Richard Casey had met McMahon to seek his commitment to reduce the conflict, the leaks and the danger of coalition instability. This unusual intervention McMahon later recorded in a written ‘aide-memoire’. There he noted Casey’s comment that he had ‘talked to Spry’ about leaks published in Inside Canberra. Director of Intelligence Charles Spry had responded that this was not his business, but he and the Governor-General had nonetheless discussed whether the Inside Canberra journalists had sources in all departments.

According to McMahon’s notes, Casey also discussed his own relationship with McEwen, saying when they were both in Menzies’ Cabinet, he had felt McEwen disliked him, but now a friendship had developed and they could trust each other. The Governor-General said McEwen ‘was a very difficult person to deal with as he lived on the edge of his nerves all the time and you never knew when he would break out’. He told McMahon that care was needed to ensure McEwen did not resign until the Country Party succession was settled between Doug Anthony and Ian Sinclair, who would otherwise have ‘a ding-dong battle’.

Despite the Governor-General’s attempt at mediation, for the next week McMahon and McEwen were locked in battle. McMahon minuted every conversation. He met Holt before the Cabinet meeting on Friday, 15 December and insisted Holt have a copy of the record of his 8 December meeting with the Governor-General. Casey had apparently already given Holt his own note of the meeting. That evening, Holt had both documents in his briefcase when he left for a weekend at the Holts’ holiday house in Portsea, Victoria.

On Sunday, 17 December, the Prime Minister disappeared while swimming at a beach near the Portsea house. The Governor-General’s role was crucial in the events that led to deputy Prime Minister John McEwen, not the deputy leader of the majority party, William McMahon, becoming the next Prime Minister. The two documents of Casey’s meeting with McMahon also became crucial when journalist Alan Reid revealed in The Power Struggle published 2 years later, that he had seen both among the contents of Holt’s briefcase. His quotes from the Casey document made public the imminent political crisis of the last week of the Prime Minister’s life.

McMahon’s ‘aide-memoire’ revealed a Governor-General apparently as concerned as the government with preserving the coalition. On Monday 18 December, the day after Holt disappeared, McEwen gave the Governor-General an ultimatum that he would not serve in a government led by McMahon. McEwen also told McMahon he would not serve under him because he did not trust him. Then, after securing the Country Party ministers’ agreement, McEwen made his position public.

Holt’s disappearance turned the McEwen–McMahon Cabinet crisis into a constitutional puzzle. Casey did not follow either of the 2 earlier precedents in determining the successor to a Prime Minister no longer able to advise him. Australia’s Constitution requires the Governor-General, as representative of the Head of State, to act only on the advice of his ministers. The 2 precedents were the Duke of Gloucester’s commissioning of deputy Labor leader Frank Forde in July 1945, after the death of Labor Prime Minister John Curtin, and Lord Gowrie’s commissioning of Country Party leader Earle Page in April 1939, after the death of United Australia Party Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. In the latter case, the reasoning was that the Country Party deputy Prime Minister was chosen only because there was no deputy leader of the majority party.

Instead, the Governor-General acted on the advice of Attorney-General Nigel Bowen and senior coalition ministers, and after 48 hours deemed the Prime Minister dead. He then commissioned John McEwen as Prime Minister of a ‘caretaker’ government until a Liberal leader was elected. The temporary nature of the role rested only on agreement, as the term of a government is decided by the parliament, not the Governor-General.

Sources

- Golding, Peter, Black Jack McEwen: Political Gladiator, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996.

- Horner, David, Inside the War Cabinet, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1996.

- Lloyd, Clem, ‘Sir John McEwen’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 15, Melbourne University Press

- Jackson, RV (ed.), John McEwen, privately published, Melbourne, 1983.

- Reid, Alan, The Power Struggle, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1969.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Press Cuttings, Senate election campaign 1964, NAA: A5954, 1118/6

- Press File, statements by Mr John McEwen, 1943–48, NAA: A5954, 2215/3

- John McEwen and William McMahon rift, 1967–68 [Personal Papers of Prime Minister Gorton], NAA: M3787, 32