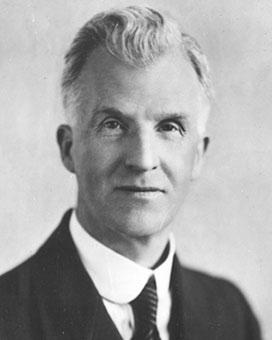

Joseph Aloysius (Joe) Lyons was Prime Minister for 7 years. His term was only 10 days less than the then record term of William Hughes. Lyons was a very successful electoral campaigner, with Enid Lyons a major factor in his winning popularity and appeal. With their family home in Tasmania, and the need to meet as many voters as possible, Lyons was the first Prime Minister to use an aeroplane to campaign.

His reputation as a cautious financial manager brought him into office, but outlasted the Depression of the 1930s. The stability of his government demanded careful management and there was a record level of ministerial reshuffling throughout his term.

Steady hand on the till

Lyons achieved the prime ministership because of his persistent pursuit of a fiscal path through the Depression years. In office, he delivered what was expected of him. He took the Treasury portfolio and instituted the program he had advocated in 1930 and 1931 of reducing debt and government spending. Lyons became the bulwark against inflation and a guarantor of debt conversion, not default.

This suited his Melbourne backers, the London bankers and the Australian voters who had resoundingly returned his government. It was not everywhere seen as the best economic solution. Opponents cited the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes and, from 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ policies in the United States, in support of more assertive economic policies to tackle the social effects of the Depression.

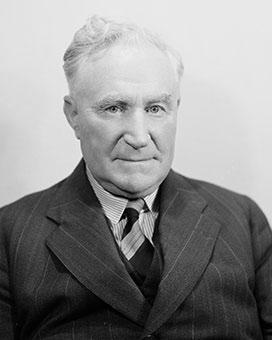

More troublesome for Lyons, however, were deep differences over tariff policy at home. Country Party leader Earle Page was hailed by Lord Beaverbrook as the champion of imperial preference, in anticipation of a wider agreement on the position taken by the Bruce–Page government. The compromise agreement at the Imperial Economic Conference in Ottawa in July and August 1932 not only disappointed the champions of free trade in England, but provoked dissent within the United Australia Party, as well as opposition from the Country Party.

In October 1933, Lyons’ co-founder of the United Australia Party, James Fenton, resigned from Cabinet over the lack of industry protection in the government’s tariff schedules. At the same time, Page attacked from the opposite position, condemning Lyons’ government for ‘the barren results’ of the Ottawa Conference. Lyons’ consensual approach was fully tested on this issue throughout his term in office.

Cabinet with a revolving door

Although in the lead-up to the December 1931 election, Lyons and Page had anticipated a coalition government, the success of the United Australia Party made an alliance with the Country Party unnecessary, at least at first.

The second Cabinet re-shuffle in the first year of Lyons’ government. Lyons and the Governor-General, Sir Isaac Isaacs (seated) after the swearing-in of new Postmaster-General Archdale Parkhill, Minister for the Interior John Perkins, and Minister for Commerce Frederick Harold Stewart. Also pictured are the Governor-General’s secretary, Leighton Bracegirdle, his new aide-de-camp Basil Finlay, and the secretary to the Executive Council, John Starling. NAA: A3560, 6257

Lyons’ first ministry was made up of United Australia Party members. The ministry comprised John Latham (Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs), George Pearce (Defence Minister), Henry Gullett (Trade and Customs), James Fenton (Postmaster-General), Archdale Parkhill (Minister for Home Affairs), Charles Marr (Minister for Works and Railways, for Health, and for Territories), Charles Hawker (Minister for Repatriation, and for Markets) and Senator Alexander McLachlan (Minister in charge of development of Scientific and Industrial Research, and Vice-President of the Executive Council).

With Lyons as Prime Minister and Treasurer and Josiah Francis as a minister without portfolio negotiating trade treaties, this made a Cabinet of 10. Lyons also appointed Stanley Bruce, Francis, John Perkins and Senator Walter Greene as assistant ministers.

But even in this first ministry, from January 1932 to November 1934, there were almost as many changes as months. Leaving aside changes for external reasons such as Bruce’s appointment as High Commissioner in London in 1933, Latham’s elevation to the High Court in 1934, or the special portfolio established for the royal visit at the end of 1934, this was a level of change exceeding even Hughes’ last ministry. An appointment of convenience like the creation in September 1932 of a ‘minister without portfolio in London’, where Bruce was attending to the family firm Paterson, Laing and Bruce, obliged the former Prime Minister much more than the new Cabinet.

Lyons himself was targeted, with Page in March 1934 trying to negotiate Bruce’s return to take leadership of the United Australia Party. From November 1934, Lyons governed in coalition, with 7 Country Party ministers (Earle Page, Harold Thorby, Tom Paterson, John McEwen, James Hunter, Victor Thompson and Archie Cameron) holding various portfolios from then until the end of the caretaker ministry of Earle Page, 3 weeks after Lyons’ death in April 1939.

Lyons’ 2 coalition ministries reflected the loss of seats in both Houses to Labor in the 1934 and 1937 elections. The inclusion of Country Party members created a Cabinet that included 2 future prime ministers (Earle Page and John McEwen), as well as former Prime Minister William Hughes, and another future Prime Minister, newcomer Robert Menzies. Latham’s seat of Kooyong was won by Menzies at the 1934 election, and he succeeded Latham as Attorney-General.

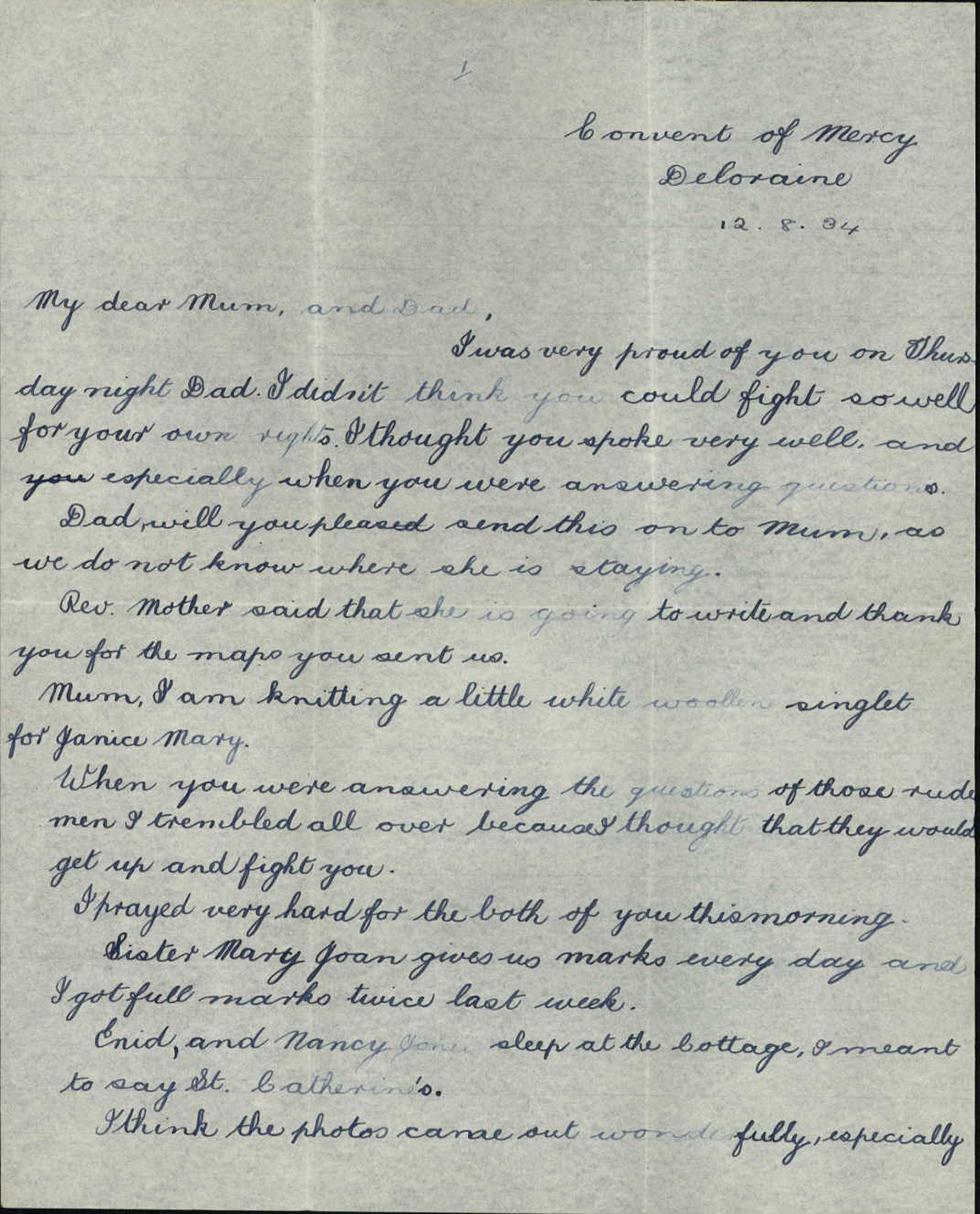

A letter from the Lyons’ 12-year-old daughter in August 1934, congratulating her father on a speech she heard on the radio and asking him for a copy. NAA: CP103/19, 58

Even key portfolios experienced change. There were 4 defence ministers in 4 years and Lyons yielded Treasury to Richard (Dick) Casey in October 1935. Lyons was forced to suspend Hughes when Cabinet moved to support the League of Nations policy of sanctions against aggressor countries, just as Hughes’ book arguing that this would lead to another war appeared. In October 1938, Charles Hawker, dropped from the ministry in 1932 and apparently on his way to challenge Lyons’ leadership of the United Australia Party, was killed when his plane crashed in Victoria. 5 months later (3 weeks before Lyons’ death), Menzies resigned as Attorney-General in protest at Cabinet’s delay in introducing national insurance legislation.

The people’s Prime Minister

Lyons enjoyed widespread popularity with voters. He seized the opportunity to cover more country in the pioneering days of air travel. In the 1934 election campaign, Lyons was piloted by Charles Ulm in the legendary ‘Faith in Australia’, to the delight of his children, who asked him for the famous aviator’s autograph. For the 1937 election alone, he travelled 9600km to hold 43 meetings in as many days. By July 1938, he had travelled 480,000km.

Bruce and James Scullin had both begun to use radio and newsreel film for campaigning and for keeping in touch with a far-flung prime ministerial constituency. Lyons added to his talents as a debater, a homely style and an apparent enjoyment in everyday things. He retained a reputation as a popular and loved figure, with an equally popular and able politician in his wife, Enid Lyons.

But by 1939, Lyons’ decreasing ability to hold his government together and Labor’s gains in the 1934 and 1937 elections had brought his leadership into question.

Sources

- Hughes, CA, Mr Prime Minister: Australian Prime Ministers 1901–72, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1976.

- Lyons, Enid, So We Take Comfort, William Heinemann, Melbourne, 1965.

- Page, Sir Earle, Truant Surgeon: The Inside Story of Forty Years of Australian Political Life, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1963.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

- White, Kate, Joseph Lyons, Prime Minister of Australia 1932–1939, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2000.