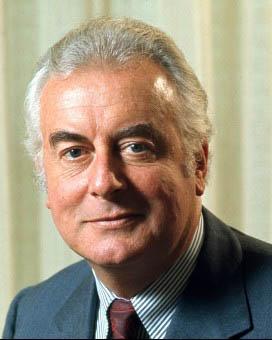

John Malcolm Fraser was Australia’s 22nd Prime Minister. Governor-General Sir John Kerr’s controversial dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam resulted in ongoing debate on the legitimacy of the Fraser government. Although the Coalition won strong majorities in both the 1975 and 1977 elections, and won a third term in 1980, the issue continued to be raised.

In Australia’s most controversial change of government, Governor-General Sir John Kerr (centre) escorts Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser (left), and Deputy Prime Minister Doug Anthony from the front door of Government House after swearing in the new ministry, 11 November 1975. NAA: A6180, 13/11/75/1

In economic policy, the Fraser government pursued the goals of reducing expenditure, streamlining the public service and providing responsible economic management. Although economic rationalism was introduced in policy debate by the Fraser government, more traditional principles of financial management and fiscal policy marked the reality of Malcolm Fraser’s prime ministerial term.

Fraser supported strong defence spending. He reinforced Australia’s diplomatic and trade relations with the countries of East and South-East Asia, seeing defence and foreign policy as key areas to forestall the spread of communism.

Fraser had an important influence on the changing relations of countries within the British Commonwealth. An unwavering opponent of apartheid, he took a strong stand in supporting reform in South Africa. He also played a prominent part in the Commonwealth’s efforts to establish an independent Zimbabwe.

During the 8 years of the Fraser government, the National Gallery of Australia was completed and construction of the new Parliament House began.

The Prime Minister is greeted by schoolchildren on his arrival for the ceremonial start of construction of the new Parliament House on Capital Hill in Canberra, 1980. NAA: A8746, KN24/9/80/45

Economic rationalism

One of the new government’s earliest actions was the appointment of an Administrative Review Committee on 22 December 1975. The brief for this body, headed by Henry Bland, was to reduce the size of the public service. A theme in the Coalition election campaign had been cutting back a federal bureaucracy that had grown large in the 30 years of post-war growth. For the Liberal leader, this was not just a campaign slogan. Fraser was convinced of the need to reduce government expansion.

In some areas, however, this meant an increase in control. Under Malcolm Fraser, the role and power of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet increased after he established 6 standing committees of Cabinet on 14 January 1976. The new committees intensified oversight of other departments’ work, and many senior officials saw the reform as ‘excessively interventionist’. Compared with the chairmanship of the four previous Liberal prime ministers (Robert Menzies, Harold Holt, John Gorton and William McMahon), ministers and staffers felt Fraser’s Cabinet meetings were both too frequent and too long.

Reducing the size of the public sector proceeded slowly. In April 1981, a committee reviewing Commonwealth functions, set up the previous November, recommended the privatisation of some government agencies. Implementation of the recommendations produced only modest savings.

In the macro-economic arena, Fraser modified, rather than led, the reform push. Within the Liberal Party in the late 1970s, the ‘new right’ emerged – followers of the economic theories espoused by Milton Friedman and known as ‘economic rationalism’. Within the party, economic rationalists were known more familiarly as the ‘dries’. Anyone on either side of the House wanting to prioritise social development or welfare measures was dubbed ‘wet’ and, by comparison, irrational.

For conservative parties in Britain, Europe and the United States, as well as Australia, economic rationalism was attractive as a coherent reworking of the classic laissez-faire economics at the source of 18th-century liberalism. Proponents within the Fraser government (increased in number after Milton Friedman came to Australia on a speaking tour) were Australia’s equivalent of the Thatcherites in Britain and the Reaganites in the United States.

Fraser, however, was not the leader of this movement and often directed policy down other avenues. He agreed with elements of the ‘dries’ program of reducing government and state intervention in the economic arena, expanding the private sector, deregulating industry and lowering tariffs. But he also stood with their opponents on some issues, including the primacy of human rights over economic and political regimes.

Supported by selected items from this new theoretical armoury, the Fraser government set out to fight inflation, and cut expenditure and taxation. When Treasury opposed the government’s plan to devalue the Australian dollar, Fraser reorganised the department. On 18 November 1976, Treasury was divided into the Department of Finance, under permanent head Bill Cole, and the Department of Treasury under (Sir) Frederick Wheeler, succeeded by John Stone in 1979. Treasurer Phillip Lynch announced the devaluation of the dollar 10 days later on 28 November 1976.

The impact of global marketing decisions on national economies was perhaps most vividly demonstrated when oil price fixing in the late 1970s by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) sent shock waves around the world. The Fraser government’s 1978 decision to price local oil at world parity was in effect a new growth tax.

By 1980, the government’s approach to inflation had produced a reduction in the budget deficit in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) from 4.8% to 1%. But this had not arrested inflation, running at 10% in mid-1980. The economic measures had also come at considerable cost in social and political terms, with unemployment at over 6%.

The 1979 federal inquiry into Australia’s financial system, chaired by Keith Campbell, did not report until two-and-a-half years later. Only one of the recommendations was implemented by the Fraser government – the entry of foreign banks into the Australian system in January 1982. Other recommendations were introduced by the Labor government after 1983.

Against the advice of Treasury, the Coalition government introduced an expansionary budget for 1982–83, with tax cuts; increased spending on roads, civil aviation and welfare housing; an increase in family allowances; and tax rebates for home mortgage interest payments over 10%. In 1983, a further $9 million was allocated for drought relief and programs for the unemployed. The resulting deficit of over $4 billion was as Treasury had predicted.

By 1983, the Australian economy was in recession, the effects worsened by severe drought.

Industrial relations

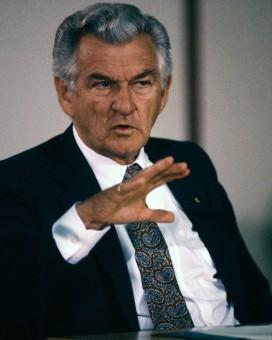

Minister for Employment and Industrial Relations Tony Street maintained good relations between the government and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and its president, Bob Hawke. This was in spite of the government’s attempt in 1976 to have the Arbitration Commission halve the wage increase sought by the unions to match the rise in the consumer price index, and the Prime Minister’s attack on the 1978 National Wage Case Decision.

Parliament passed the Commonwealth Employees (Employment Provisions) Act 1977 in August, but the law was not enacted until 2 years later when it was used against Commonwealth employees engaging in ‘go-slow’ action.

In March 1981, the government used the threat of a tariff protection review to secure an agreement by the Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) corporation that it would reject the 35-hour week sought by workers at its South Australian plant. In July 1981, the government and the ACTU (headed by Cliff Dolan after Bob Hawke entered parliament in October 1980) negotiated a means to achieve greater pay rises within the indexation system. The head of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission, John Moore, responded to this deal-making by abandoning the wage-setting system, following the lead of both the government and the ACTU. The resulting wages break-out in 1981–82 made a Commonwealth–states wage pause agreement essential and this was achieved in December 1982.

Environment

The Fraser government’s record on environmental issues is mixed. In its first year, it implemented the recommendation of the 1975 Commission of Inquiry on Fraser Island, ending all sand mining on the Queensland island.

On 23 August 1977, the government announced that the mining and export of uranium would be permitted under strict guidelines, including in the controversial Jabiru region on the western edge of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory.

Malcolm Fraser with Yolngu leader Galarrwuy Yunupingu at the uranium-mining township of Jabiru in Arnhem Land, May 1978. NAA: A6180, 4/5/78/62

In April 1979, the government proclaimed an adjacent area Kakadu National Park. In June, the government prohibited exploration and drilling for petroleum on the Great Barrier Reef and, in October, declared the Capricornia section of the reef the first stage of a protected Great Barrier Reef marine park.

In March 1978, the Fraser government set up an inquiry into whales and whaling. The inquiry argued for an end to whaling in Australia and that Australia join the nations lobbying for an international ban on whaling. In April 1979, the whaling industry ceased in Australia. Among the international instruments Australia signed during the Fraser government were a convention against trading endangered species, a convention on the conservation of seals in Antarctica and a convention on the international importance of wetlands.

Questions about the impact of international agreements on national sovereignty had been raised during Gough Whitlam’s prime ministerial term. The Fraser government’s environmental agreements meant this debate continued. It had immediate implications in Australian electoral politics, fuelling the ongoing debate about ‘new federalism’. In Opposition, Fraser had firmly promoted the protection of states’ rights against federal government encroachment. This conviction was behind his government’s refusal to use Commonwealth powers to stop the construction of the Franklin Dam in Tasmania in 1982. Resisting the dominance of the federal government over the states had been a key issue in the 1975 election. In the 1983 election campaign, the debate over the Franklin Dam raised awareness of the need for national, as well as international, standards of environmental protection.

Australian society

Fraser’s term as Prime Minister, from 1975 to 1983, had an effect in shaping Australian society comparable with that of Robert Menzies’. The implementation of laws governing the relations between Australians suggests Fraser’s outlook. The most notable legislation for First Australians, the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, was an amended version of legislation introduced by the Labor government. The Fraser government also passed the Human Rights Commission Act 1981, giving effect to five international human rights instruments, and established the Human Rights Commission. This government also established the position of Commonwealth Ombudsman in 1977, reviving a Labor Bill that had been stalled in the Senate. It also enacted Australia’s first freedom of information law in 1982.

But the impact of the Fraser government can best be seen in its revitalised immigration program. From 1975 to 1982, some 200,000 migrants arrived from Asian countries, including nearly 56,000 Vietnamese people who applied as refugees. In addition, policies were put in place to grant entry to 2059 ‘boat people’ – refugees from Vietnam who arrived without documents or official permission after hazardous sea voyages to the northern coast of Australia. The immigration program focused on resettlement and multiculturalism. In 1978, the Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs was created. Petro Georgiou, the Prime Minister’s immigration adviser, suggested in retrospect that:

Viewed in the longer run it was the entry of Vietnamese refugees that made Australia’s migrant intake multiracial . . . it was under [Fraser’s] management that Australia first confronted the real consequences of abolishing the White Australia Policy.

On 1 September 1977, a review of the effectiveness of migrant services and programs was chaired by Frank Galbally. As a result of the input from migrant communities, the Fraser government established migrant resources centres, provided funds for English language teaching and improved translator services, and developed radio and television services for different ethnic groups.

The Prime Minister with officials on a visit to the Torres Strait Islands, 1976. NAA: A8281, 25/11/76/73

International relations

As a peacetime prime minister, perhaps Fraser’s most notable contribution was in Australia’s relations abroad. Journalist Paul Kelly observed in 2001:

The unifying theme behind all Fraser’s foreign policy was a pragmatic and independent search for the Australian national interest. When speaking for Australia abroad he was consistently informed, formidable and constructive.

But a brief overview of Fraser’s activities abroad suggests that to this summary should be added his influence on the changing relations of countries within the British Commonwealth.

In the Australasian region, the policies of the Fraser government were directed towards reducing the threat posed by communism and developing favourable trade relations. In June 1976, Malcolm Fraser visited the People’s Republic of China, a promotion of relations that made the policy forged by the Labor government of Gough Whitlam a bipartisan one. Fraser was critical of US President Ronald Reagan’s policy towards China, arguing that the preoccupation of the United States with the Soviet Union limited the building of vital relations with China.

The Fraser government supported the role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in maintaining the stability of Australia’s neighbourhood. Like Gough Whitlam, Fraser paid for stability by failing to support East Timor. In 1978 Australia recognised Indonesia’s incorporation of East Timor, achieved via a military takeover in 1976. Reflecting different political imperatives, however, the Fraser government strongly opposed Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia. Australia also backed US security initiatives in relation to Japan and South Korea.

In September 1976, Fraser made overseas visits to Papua New Guinea for Independence Day celebrations, Singapore, Canada, Indonesia and New Zealand where he attended a meeting of the South Pacific Forum. In May and June the following year, he visited Italy, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and the United States. In Europe, he raised Australia’s objections to the protectionist policies of the European Economic Community. At the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Scotland, he argued strongly for widespread opposition to apartheid and support for African countries, including global agreements to stabilise commodity prices. The Gleneagles Agreement against apartheid in sport was reached at this meeting.

Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser with the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Andrew Peacock, and the Indonesian Foreign Minister Professor Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, 1978. NAA: A6180, 15/12/78/5

On a visit during the Australian parliamentary recess in 1978, Fraser travelled to the United States where trade talks resulted in an agreement for increased imports of Australian beef. In September that year, he attended the 9th South Pacific Forum in Niue. In December, he visited Jamaica en route to the United States for talks with President Jimmy Carter aimed at developing greater military cooperation. He then visited India at the invitation of Prime Minister Morarji Desai.

US President Jimmy Carter with Malcolm Fraser and Andrew Peacock at the White House, 1980. NAA: A6180, 18/3/80/6

In August 1979, Fraser attended the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Zambia. At this meeting, and the follow-up at Lancaster House in London later that year, the Australian Prime Minister’s influence was a key factor in the progress towards independence for Zimbabwe. The supervised elections and Commonwealth-monitored ceasefire produced the first majority representation in the former Rhodesia, and made Robert Mugabe the Prime Minister of Zimbabwe. At the independence celebrations in Salisbury in 1980, Fraser’s contribution was firmly acknowledged.

Fraser’s emphasis on international relations might have been a factor in his lack of focus on declining electoral support in the second half of his term. In 1980, the government’s majority was halved, while Labor leader Bill Hayden increased Opposition numbers. With Fraser’s support weakening, Andrew Peacock mounted an unsuccessful challenge for party leadership. Fraser’s plans for an early election in 1982 collapsed when he was hospitalised for a back injury.

At the 1983 election, the Labor Party won with a large majority and Bob Hawke replaced Fraser as Prime Minister.

Sources

- Ayres, Philip, Malcolm Fraser: A Biography, William Heinemann Australia, Melbourne, 1987.

- Edwards, John, Life Wasn’t Meant to be Easy: A Political Profile of Malcolm Fraser, Mayhem, Sydney, 1977.

- Kelly, Paul, ‘Malcolm Fraser’, in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland, Sydney, 2000.

- Nethercote, John (ed.), Liberalism and the Australian Federation, Federation Press, Sydney, 2001.

- Renouf, Alan, Malcolm Fraser and Australian Foreign Policy, Australian Professional Publications, Sydney, 1986.

- Schneider, Russell, War Without Blood: Malcolm Fraser in Power, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1980.

- Viviani, Nancy, The Indochinese in Australia, 1975–1995: From Burnt Boats to Barbecues, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1996.

- Weller, Patrick, Malcolm Fraser PM: A Study in Prime Ministerial Power, Penguin, Melbourne, 1989.

- Whitwell, Greg, The Treasury Line, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Devaluation, NAA: M1356 File 58