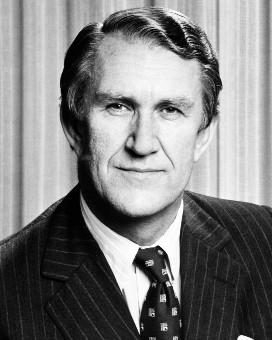

Robert James Lee (Bob) Hawke led the Labor Party’s return to office in the election on 5 March 1983, and to a record 4 terms with election wins in 1984, 1987 and 1990. Hawke proceeded with some caution in moving the Labor Party to the middle ground, drawing upon his wide popularity to win consensus for the government’s systematic economic reforms.

The key issues of the Hawke government were globalisation, micro-economic reform and industrial relations. The opening of Australian finance and industry to global competition and the restructuring of the role of trade unions represented one of the most extensive undertakings of micro-economic reform in Australia’s first century. Although 2 million new jobs were created, the changes also contributed to a recession. By 1992, unemployment had reached 11%, the highest level since the Depression of the 1930s.

Hawke’s links with business and with trade unions, both developed in his long career with the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), helped achieve the necessary agreements for these reforms. Critics complained that Hawke had ‘hijacked’ the Labor Party and moved it to the right.

Cabinet

With only 7 years since Labor had last formed government, there was considerable talent in Caucus. Hawke broke with Labor tradition by creating an inner Cabinet and an outer ministry. In the 13-member Cabinet sworn in on 11 March 1983, Lionel Bowen was the deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Trade, and Bill Hayden was the Minister for Foreign Affairs (the condition of Hayden’s agreement to resign the party leadership). The other 10 Cabinet ministers were John Button (Industry and Commerce), Ralph Willis (Employment and Industrial Relations), Paul Keating (Treasurer), Senator Gareth Evans (Attorney-General), Gordon Scholes (Defence), Senator Susan Ryan (Education and Youth Affairs, and Women’s Affairs), Senator Don Grimes (Social Security), Stewart West (Immigration and Ethnic Affairs), Peter Walsh (Resources and Energy) and Mick Young (Special Minister of State).

The 14 members of the outer ministry were Peter Morris (Transport), John Kerin (Primary Industry), Kim C Beazley (Aviation), Chris Hurford (Housing and Construction), John Brown (Sport, Recreation and Tourism), John Dawkins (Finance), Neal Blewett (Health), Barry Jones (Science and Technology), Michael Duffy (Communications), Barry Cohen (Home Affairs and Environment), Allan Holding (Aboriginal Affairs), Senator Arthur Gietzelt (Veterans’ Affairs), Tom Uren (Territories and Local Government) and Brian Howe (Defence Support).

The Hawke government’s 1983 select committee on electoral reform recommended expansion of the parliament for the first time since 1949, and the establishment of an Australian Electoral Commission. In 1984, the House of Representatives increased from 125 to 148 members. The Senate increased from 60 to 76 senators. For the election on 1 December 1984, there were 23 new electorates and 16 additional Senate seats.

Hawke’s second ministry, sworn in on 13 December 1984, also numbered 27, but this time the ratio of ministers to backbenchers was slightly improved. The increased seats provided 55 Labor backbenchers compared with only 48 in the government’s first term.

Bob Hawke's third ministry on the steps of Government House, after the swearing-in after the 1987 election. NAA: A8746, KN24/7/87/2

Hawke’s third ministry was sworn in on 24 July 1987 after the federal election on 11 July, and the fourth ministry on 4 April 1990, after the 24 March election.

Consensus and the economy

Just as the election slogan ‘Bringing Australia together’ promised, Bob Hawke’s ‘consensus’ style was evident from the first. A month after taking office, the government held a National Economic Summit in Canberra, 11–14 April 1983. The summit involved all political parties, unions and employer organisations and aimed to form a national consensus on economic policy. Hawke’s links with business, built up during 22 years at the ACTU, were an effective foundation for such an approach, if an unusual one for a Labor Prime Minister.

A Prices and Incomes Accord with the trade union movement had been forged before the election, and announced in the election campaign in February 1983. Improvements in economic performance were pursued by other consultative means, including a Tax Summit, the Economic Planning Advisory Council and the Australian Labor Advisory Council. The level of industrial dispute dropped and the only prolonged dispute was with airline pilots in 1989. The Hawke government intervened to end the dispute in order to protect general pay restraint.

The government’s policies strengthened business enterprise in Australia, dampening the usual tension between that sector and a Labor government. Instead Hawke faced internal conflict arising from persistent left-wing criticism that he had ‘hijacked’ the Labor Party and moved it to the right. His friendships with leading businessmen such as Peter Abeles added fuel to these criticisms.

Labor came to power in 1983 and inherited a deficit of $9000 million. This economic crisis informed much of the Hawke government’s policy-making. The priority was to restore economic and employment growth by reducing high unemployment and inflation. Hawke, and his Treasurer Paul Keating, regarded good management of the ailing economy as vital. Both also believed the only solution lay in finding a structural and policy path that accommodated both labour and business.

This path was designed to increase the efficiency and competitiveness of Australian industry. Complementary industrial relations policies involved award restructuring and the introduction of enterprise bargaining. Despite the irony of a former trades union leader introducing these revolutionary changes, the Prices and Incomes Accord reduced industrial disputes, increased the social wage, and gave workers access to superannuation.

Financial assistance to low-income families was also increased. This achievement was overshadowed by Hawke’s characteristically buoyant claim that ‘By 1990 no Australian child will live in poverty’. The government also adopted policies integrating employment, education and training and acted to improve school retention rates.

The Whitlam government’s Medibank scheme had been partially dismantled under the Fraser–Anthony Coalition government. Hawke established a new, universal system of health insurance under Medicare. The government also obtained agreement with the States on a single-gauge national rail system.

The consensus rather than confrontation approach was also effective with voters. The Hawke government was re-elected in 1984, 1987 and 1990 in campaigns described as increasingly presidential. This record, for a Labor government, of four successive terms reflected Hawke’s considerable and persisting popularity.

Hawke was a great celebrator and made the most of commemorative opportunities. Although a contentious national anniversary, in 1988 the Hawke government encouraged Australia-wide celebrations of the bicentenary of the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove. The year-long celebrations included the opening of the new Parliament House in Canberra on 9 May 1988. Malcolm Fraser had formally initiated construction in January 1981, after architects Mitchell/Giurgola and Thorpe won the design competition. Hawke had ceremonially laid the foundation stone on 4 October 1983.

Globalisation and the economy

The greatest impact of the Hawke government flowed from the economic reforms that abandoned the traditional Labor reliance on tariffs to protect industry and jobs. During its term from 1983 to 1991, the government reduced the protection of Australian business and industry, increasing competition and at the same time achieving improved employment participation. Efficiencies in the tax system were also introduced.

In its first five years, from 1983 to 1987, the government decided on the moves to deregulate Australia’s financial system. This involved ‘floating’ the Australian dollar (rather than tying its value to a gold standard or to another currency), and removing controls on foreign exchange. Direct controls on Australian interest rates were also removed, and foreign competition in banking was permitted. In its third term, from 1987 to 1989, the Hawke government abolished Australia’s 2-airline policy, removed export controls on bulk commodities and extended general tariff reductions.

Reforms introduced from 1990 to 1991 included another crucial change – opening Australia to competition in the telecommunications industry. As well, the reduction of all tariffs to 5% and the phasing out of textile, clothing and motor vehicle protection was introduced.

Environment

The Hawke government followed the Whitlam government’s lead, with an increased emphasis on protecting the environment. Like Whitlam, Hawke used the instrument of Section 52 of Australia’s Constitution, the ‘external affairs power’. The decision of the High Court in the Franklin Dam case in 1983 meant that although the States had control over their own land matters, when Australia became party to international agreements for environmental protection, Commonwealth laws would override State laws.

Enactment of the World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983 thus gave the Commonwealth responsibility for all places listed as world heritage areas. The government moved for world heritage listing of Tasmania’s forests and the North Queensland rainforests.

The contentious issue of uranium mining, which had contributed to Bill Hayden’s loss of party leadership, became an environmental issue under Hawke. The government banned new uranium mining at Jabiluka, on the western border of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, and gave a highly publicised priority to the world heritage listing of Kakadu National Park.

Human rights

Hawke took steps towards reconciliation with Indigenous Australians and proposed a treaty. In 1989, the Department of Aboriginal Affairs was replaced with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission as the main administrative and funding agency for Indigenous people.

The Hawke government also addressed the issue of gender inequity. Hawke appointed Senator Susan Ryan minister assisting the Prime Minister for the Status of Women (changing the title from Women’s Affairs 2 months into his first term). The government developed a National Agenda for Women and established the Affirmative Action Agency. The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 put gender discrimination in workplaces outside the law.

International affairs

Bill Hayden was Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Hawke government until he resigned from parliament on 17 August 1988 to become Governor-General. Senator Gareth Evans, a Hawke protégé, then took the Foreign Affairs portfolio. Hawke favoured a ‘personal diplomacy’ to raise Australia’s international profile in the United States, Russia, China, Japan and Southeast Asia. Hawke also continued to be an active supporter of peace negotiations in the conflict between Palestine and Israel.

In 1990, Hawke faced his least expected but most demanding international challenge, the ‘Gulf War’. The Australian government promptly supported United Nations sanctions when Iraq invaded Kuwait, and sent Navy ships, then troops, to join UN forces against Iraq.

Deposed 1991

The economic reforms of the 1980s owed much to close cooperation between Hawke and Treasurer Paul Keating. With the deterioration of the Australian economy by 1990, their working relationship also disintegrated and their rivalry intensified. With economic gains dissolving, support for the government dropped abruptly, as did Hawke’s almost legendary popularity and authority.

Just as Hawke had done with Bill Hayden 10 years before, Keating provoked an open leadership contest in 1991. Keating claimed that Hawke had reneged on an agreement reached at Kirribilli House in 1988 about the transfer of the leadership. Hawke won a leadership ballot in mid-1991 and Keating retired to the back bench, giving up the Treasury portfolio.

On 12 December, a deputation of Hawke’s ministers – Kim C Beazley, Michael Duffy, Nick Bolkus, Gareth Evans, Gerry Hand and Robert Ray – advised him to resign. He resisted, and a week later was persuaded to call another leadership vote. He was narrowly defeated by Keating, who became party leader and was sworn in as Prime Minister on 20 December 1991.

Sources

- Blewett, Neal, ‘Robert James Lee Hawke’ in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland Publishers, Sydney, 2000.

- Catley, Bob, Globalising Australian Capitalism, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1996.

- Hawke, Bob, The Hawke Memoirs, William Heinemann Australia, Port Melbourne, 1994.

- Hawke, Hazel, My Own Life: An Autobiography, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1992.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.