Alfred Deakin was born on 3 August 1856, in Collingwood, Melbourne. His parents, William and Sarah Deakin, emigrated from England in 1849. Their first child, Catherine, was born shortly afterwards.

When he was 7, Alfred Deakin went to Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. At 16, he began studying law at the University of Melbourne. He was a keen member of the university’s debating club and other societies promoting radical thought, including spiritualism. The 16-year-old was also the editor of a spiritualist paper. When he became a barrister in 1878, he had already written a play (Quentin Massys) and published a long book, A New Pilgrim’s Progress. His law career was slow to grow and, for several years, he earned money writing for a leading Melbourne newspaper, The Age, after meeting its editor, David Syme, in 1878.

Syme was influential in the development of his protégé’s ideas, prompting Deakin to change from a belief in free trade to become a protectionist. Syme also helped him to win the rural seat of West Bourke in the Victorian parliament in 1879. Deakin resigned in his maiden speech on 8 July 1879, claiming irregularity in the poll. He lost the subsequent by-election, but was re-elected in July 1880 and held the seat for 10 years.

Alfred Deakin and Elizabeth Martha Anne (Pattie) Browne, a fellow spiritualist, were married in 1882. They lived with Deakin’s parents for the next 5 years. In 1887, they moved with their two small daughters, Ivy and Stella, to their brand-new house, ‘Llanarth’, in Walsh Street, South Yarra. Their third daughter, Vera, was born there in 1891.

Beginning a political career

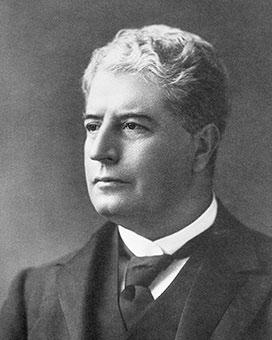

Deakin was an impressive man – dark, handsome and tall, with a rich voice and a keen mind. He became Commissioner for Public Works and Water Supply in 1883, and Solicitor-General and Minister of Public Works the following year. In 1885, Deakin secured the passage of the colony’s pioneering Factories and Shops Act, enforcing regulation of employment conditions and hours of work.

In 1887, Deakin led Victoria’s delegation to the Imperial Conference in London. He was a young colonial politician who made a strong impact arguing forcibly for more favourable terms in the colonial naval agreement. He also argued for an Australian role in colonising the Pacific. With Queensland’s delegate, Samuel Griffith, he confronted the British Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, on colonial interest in the New Hebrides.

Deakin was a passionate campaigner for irrigation. In 1884, he chaired a royal commission on irrigation and, on an inspection tour to California, met George Chaffey and William Chaffey. The Chaffey brothers subsequently demonstrated their novel irrigation techniques at Mildura in 1886, when Deakin was Minister for Water Supply. Deakin also introduced a radical bill into the Victorian parliament that, if it had passed, would have made all natural waters in the colony publicly owned and enabled the construction of irrigation works. In 1890, he travelled to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India, and published an account of South Asian irrigation in 1893. By that time, however, Deakin’s paper generated little interest since both drought and economic depression had struck Australia’s eastern colonies.

After the fall of the government in October 1890, Deakin remained a backbencher throughout the 1890s. Like many others, Deakin lost heavily in the 1893 financial collapse and had to practise law to supplement his salary and repay his debts. His frustration that the competitive divisions between the colonies prevented a united front at the 1887 Imperial Conference fuelled his support for Federation throughout the 1890s.

For Federation

In 1890, Deakin was Victoria’s delegate to the Australasian Federal Conference, held in Melbourne, which agreed to hold an intercolonial convention to draft a federal constitution. The following year, Deakin was the colony’s delegate to this meeting, the first National Australasian Convention held in Sydney, which produced a draft Constitution Bill.

Deakin became Victoria’s most prominent federationist. His splendid oratory enlivened meetings throughout Victoria, from the annual conference of the Australian Natives Association in 1893, to the public meetings leading up to the Federation referendum in June 1898. Deakin was founding chairman of the Federal League of Victoria in 1894, and attended the Federal Council meeting in Hobart in 1896.

Representatives of the colonial parliaments at the Australasian Federal Conference, Melbourne, February 1890. Standing, left to right: AI Clarke (Vic); Captain Russell, Colonial Secretary (New Zealand); Samuel Griffith (Qld); Sir Henry Parkes (NSW); T Playford (SA); Alfred Deakin, Chief Secretary (Vic); Stafford Bird, Treasurer (Tas); GH Jenkins, Secretary to the Conference. Seated, left to right: William McMillan, Colonial Treasurer (NSW); John Hall (New Zealand); JM Macrossan, Colonial Secretary (Qld); Duncan Gillies, Premier of Victoria and Chairman of the Conference; John Cockburn (SA); James Lee Steere (WA). NAA: A1200, L13363

In 1897, he was a delegate to the second Australasian Federal Convention, which opened in Adelaide in March 1897 and concluded in Melbourne in January 1898.

Vida Goldstein's petition to Edmund Barton, seeking legislation for female suffrage, 1901. NAA: A6, 1901/354

Deakin and the Victorian Premier, George Turner, ensured the Constitution Bill passed the Victorian parliament and could be put to the colony’s voters at an 1898 referendum. South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria were the first colonies to pass Federation referendums. Between April and September 1899, successful referendums were held in all colonies, except Western Australia, enabling the Bill to be submitted to the British parliament.

In 1900, Deakin was a member of the delegation led by Edmund Barton to lobby in London for the successful passage of the Australian Constitution Bill through the British parliament. The joy of the delegates when the Bill was passed in June, was exceeded only by the triumph in every colony when the news was received that it had become law with Queen Victoria’s assent on 9 July 1900.

Before the inauguration of the nation on 1 January 1901, Deakin played a strategic role in undoing the ‘Hopetoun blunder’ – the first Governor-General’s failure to select Edmund Barton to be the first Prime Minister. Deakin, Victorian Premier George Turner, and Deakin’s mentor David Syme, were the major force in ensuring, after a tense few days of negotiation, that Lord Hopetoun reversed his choice of William Lyne.

On Christmas Day 1900, Barton chose his ministers and, on 1 January 1901, the Governor-General administered the oaths of the first ministry and Alfred Deakin became Australia’s first Attorney-General.

The first parliament

After the first federal elections in March 1901, Deakin served as leader of the House, as well as Attorney-General. He had a heavy workload throughout the first parliament, with its mass of machinery bills, as well as policy legislation on immigration. Robert Garran took major responsibility for drafting legislation, though Deakin himself was substantially responsible for the Public Service and Conciliation and Arbitration bills.

Deakin had a keen intelligence and great capacity for hard work, and he was persuasive and admired. His even temper and pleasant manner earned him the nickname ‘Affable Alfred’. When Deakin walked to Parliament House from his home in South Yarra, he would be waylaid by colleagues eager for his conversation, not on politics, but on literature, philosophy, and the other interests that made him a wide-ranging reader and thinker.

On 18 March 1902, Deakin made a speech to introduce the Judiciary Bill. The speech is considered among the finest of his parliamentary career, and indeed now rated among the finest speeches of the parliament’s first century. He called the Judiciary Bill ‘the foundation of Commonwealth law’. Deakin had ensured that Samuel Griffith had a major role in drafting the Bill and, as Attorney-General, Deakin introduced it in the House. Among those saluting the eloquence of his 3.5-hour speech were his friends Richard O’Connor and artist Tom Roberts – although Roberts confessed he had not stayed the entire course.

With the support of Edmund Barton and Isaac Isaacs, Deakin argued forcefully against delaying the establishment of the High Court. He viewed the Court as the essential third pillar of the federal structure once the parliament and public service were in place. The Bill was not passed until September 1903 and, in a compromise with budget-wary opponents, the High Court bench was reduced from 5 to 3 judges.

In 1902, Deakin served as Acting Prime Minister from May to September, while Edmund Barton was overseas for the coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. Atlee Hunt, a Sydney protégé of Barton and Secretary of the Department of External Affairs, took a leading role in dealing with the prime ministerial business. During Barton’s absence, Hunt and Deakin developed the working relationship that extended over the next decade, during Deakin’s 3 terms as Prime Minister between 1903 and 1910.

The British government's acknowledgment of the establishment of Australia's High Court and Alfred Deakin's new office as Prime Minister. NAA: A6661, 1064, p. 1

In July 1903, Deakin took over the conduct of a second bill vital to implementing a provision of the Constitution, the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. This controversial measure had its first casualty with the resignation of Charles Kingston over a Cabinet amendment to exclude seamen on coastal ships. The Bill brought down two governments, and split Deakin’s Protectionist supporters, before agreement was hammered out and the statute enacted in December 1904.

By September 1903, when he became Prime Minister in his own right, Deakin had nearly as much experience managing government as Barton himself.

Sources

- La Nauze, JA, Alfred Deakin: A Biography, Vol. 1, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1965.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Summary of work in the Attorney-General’s Department, 1902–03, NAA: A432, 1929/2611