Elizabeth Martha Anne (Pattie) Browne was born in 1863, and married Alfred Deakin in 1882, when she was 19 years old. Their 3 children, Ivy, Stella and Vera, were born between 1883 and 1891 while Deakin was a member of the Victorian parliament.

Neither ‘Llanarth’, the Deakins’ house in South Yarra, nor the retreat at Point Lonsdale where they built ‘Ballara’, were used as official prime ministerial residences. Deakin chose to invite home only his closest friends, Edmund Barton and Richard O’Connor, among his colleagues. This was not from a reluctance on Pattie Deakin’s part, but because Deakin insisted his public world be excluded from the homes where he could live his ‘inner life’.

Pattie Deakin was not relieved of an official role as prime ministerial wife, however. She had accompanied Deakin to London in 1900 and was active in the delegation lobbying for the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Bill. She also took part in the ceremonial opening of the first parliament in Melbourne on 9 May 1901 and in the festivities in Melbourne. These included the reception for the Duke and Duchess of York on the evening of the opening of parliament, where the Deakins’ eldest daughter, Ivy, made her debut. The opportunity could not be missed; with the British empire still in mourning for the death of Queen Victoria on 22 January, there were neither balls nor banquets.

Alfred and Pattie Deakin in 1907.By permission National Library of Australia. Pic Album 382

Pattie Deakin created an informative record of her duties on an official visit to Britain in 1907. Her reports to her family include a description of the Freedom of the City of London ceremony, when she and Alfred Deakin motored slowly through bedecked streets lined with crowds cheering and cooeeing. She also wrote of her gratification not only that the Prime Minister was treated as ‘the first man of the hour’, but that she also was treated as ‘a person of great prominence’ and that ‘cheers greet me even though I am not a titled individual’.

The couple took a suite at the Hotel Cecil, overlooking the Thames and Westminster, as their base in the ‘whirlwind of activities’ of the Imperial Conference. There, the prime ministerial wife dealt with an endless stream of ‘callers, messengers and interviewers’ in between:

a luncheon, then ... a reception, then a tea, dress for dinner, motor again to a reception and drop into bed in tears overtired and feeling it quite impossible to do the list of the next day’s engagements.

On this visit to Britain, she also undertook some speaking engagements, including a talk to the Primrose League, a conservative group that, with the Women’s Liberal Foundation (formed in London at the turn of the century), ‘made the open participation of women in politics respectable’. Littleton Groom recalled that, in Britain, Pattie Deakin made an indelible impression of ‘Australian womanhood at its best’.

On returning to Australia, Pattie Deakin took on the organisation of a national Exhibition of Women’s Work held in 1907. She was active in the ‘Deakinite’ Liberal Party, formed in 1909, and she campaigned for Deakin in the 1910 general election.

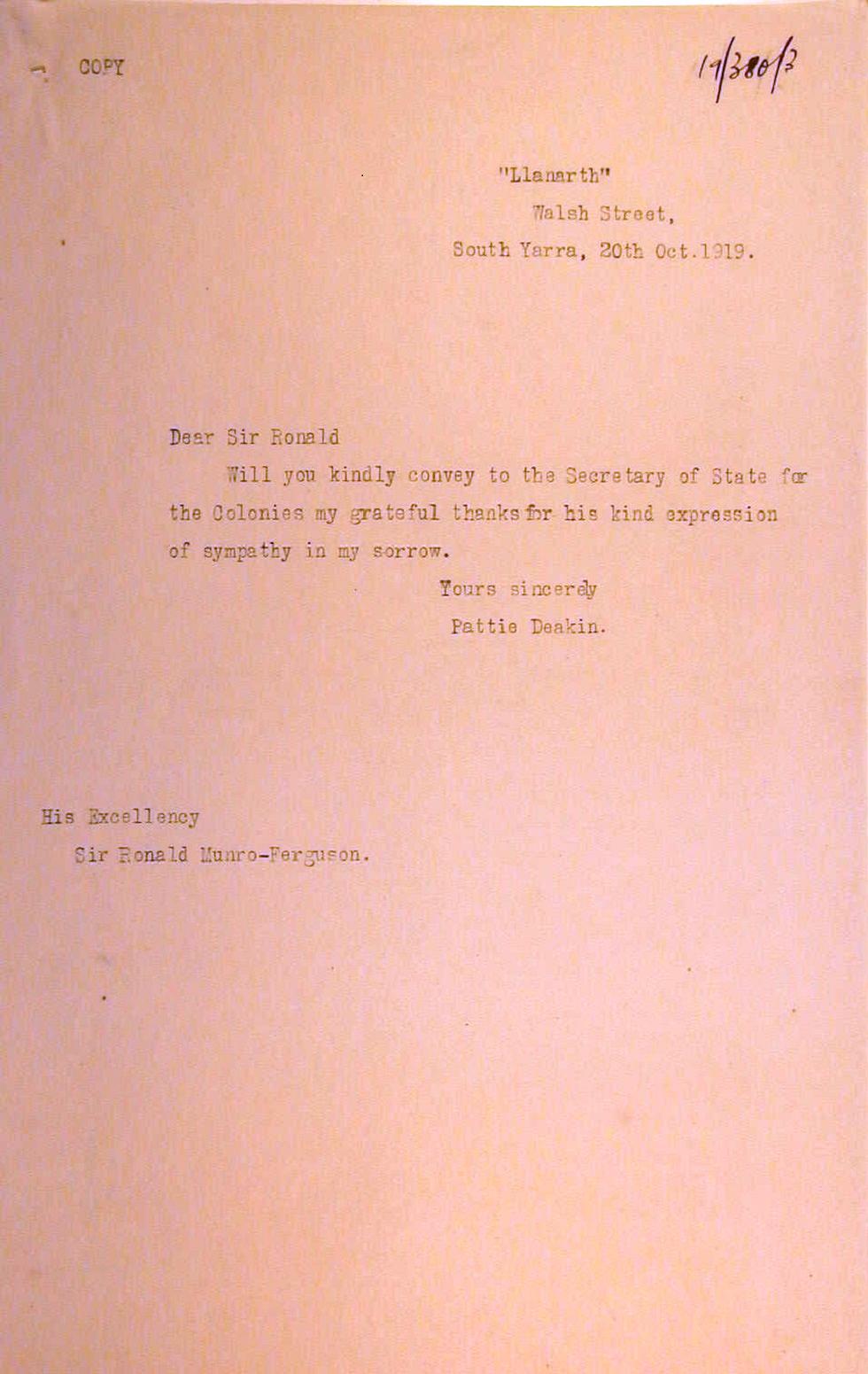

Letter of condolence from Sir Roland Munro Ferguson to Pattie Deakin, 20 October 1919. NAA: A11804, 1919/380, p. 7

Although only fragments of information indicate Pattie Deakin’s work as prime ministerial wife, these fragments point to an essential, if implied and undefined, official role. The relationship between this role and her activities in organisations such as the National Council of Women in Victoria, the Lyceum Club and the kindergarten movement, awaits detailed investigation.

Pattie Deakin died on 30 December 1934. The award of her Commander of the British Empire for her contribution to public life was announced 2 days later in the New Years honours.

Sources

- Langmore, Diane, Prime Ministers’ Wives: The Public and Private Lives of Ten Australian Women, McPhee Gribble, Ringwood, Victoria, 1992.