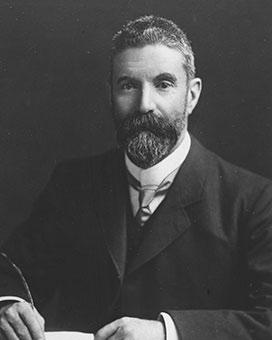

A tradesman with only a few years formal schooling, John Christian (Chris) Watson arrived in Australia in 1887, aged 20. Within 3 years, he had a job, a wife, and a cause – labour politics.

Early years

Watson was probably born in Valparaiso, Chile on 9 April 1867, the only son of Martha and Johan Tanck. When Watson was 2, his mother married George Watson, and the family lived in New Zealand. At the age of 10, Watson left school to work on a railway construction site. Aged 13, he was apprenticed as a newspaper compositor. On becoming a qualified tradesman, he joined the local typographers union.

Watson migrated to New South Wales 6 years later, where he worked in Sydney on the Daily Telegraph newspaper, the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper and, from 1888, the Australian Star, a protectionist newspaper. On 27 November 1889, he married Ada Jane Low, a Sydney seamstress. 3 months later, aged 22, he was elected typographical union delegate to the New South Wales Trades and Labour Council.

A handsome young man, strong and athletic, Watson was a rower and footballer who was just as proficient at cards and billiards. Already recognised for his common sense, courage and ease with people, Watson readily involved himself in the rapidly growing labour movement in New South Wales.

The rise of labour politics 1889–1901

Intercolonial trades union conferences held during the 1880s brought together delegates from unions large and small, uniting shearers, seamen and seamstresses. The vigour and commitment of the movement was unforgettably signalled to British, as well as colonial governments, in 1889. That year, the London dock strike was won with the donations of unionists in Sydney and Brisbane. The sums collected in the Australian colonies far exceeded the total raised throughout Britain.

The crushing of the intercolonial maritime strike in November 1890 was a major factor in the surge of labour political organisation – a striking phenomenon, widely recorded by poets, writers, and painters. Alfred Deakin observed in 1891 that the rise of labour in politics ‘is more significant and more cosmic than the Crusades’.

By 1891, 4 of the 6 Australian colonies had labour political organisations set up to gain better representation of labour in the colonial parliaments, with the fifth, Western Australia, following in 1893. In Queensland the Australian Labour Federation was formed in 1889. In South Australia the United Labor Party began in 1891. The same year a Progressive Political League formed to provide a political base for labour interests in Victoria. In New South Wales, Watson was closely involved in establishing the Labour Electoral League in 1891. He was the first secretary of the League’s West Sydney branch, and prominent in the campaigning that returned 35 Labor members to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in June 1891.

In January 1892, Watson was elected vice-president of the Trades and Labour Council. He successfully negotiated agreement when the Council was in conflict with the Labour Electoral League executive. He led a deputation to Macquarie Street on 15 September 1892 in support of the striking miners at Broken Hill, aimed at uniting Labor parliamentarians in support of George Reid’s censure motion against the New South Wales government. As the depression of the 1890s worsened, Watson agitated for assistance for the thousands who were unemployed by 1893. In 1894 he helped run a cooperative settlement for the jobless.

His passionate conviction that solidarity was essential to the labour cause was nowhere more evident than at the unity conference he organised for 9 to 11 November 1893 at Millers Point, a wharf-side suburb of Sydney. From the chair Watson turned a chaotic meeting into a productive one. Participants agreed to a stronger solidarity pledge for parliamentary representatives and the expulsion of dissidents. At the annual party conference in March 1894, Watson outshone even William Holman and William Hughes in his role in establishing what would become the key principles of an Australian Labor Party: the authority of the party conference, the role of the executive, the parliamentarians’ pledge and caucus solidarity.

In July 1894, Watson won the New South Wales seat of Young, joining the parliamentary Labor Party led by Joseph Cook. The following year, William Hughes took a Labor seat in New South Wales. All 3 future prime ministers retained their seats until they resigned to stand for the first federal election in March 1901.

Federal Labor leader 1901

On 8 May 1901, at the inaugural meeting of the first Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, Watson was elected leader. The first federal parliament was ceremonially opened the next day and, on 10 May, the House got down to business. Edmund Barton’s Protectionist government was dependent on Watson’s support to pursue its legislative program. For Labor, free trade meant a loss of protection for wages and conditions, and for nourishing local employment. A fragile alliance was built around this issue.

With Alfred Deakin the Prime Minister from September 1903, cooperation between the 2 parties was strengthened as a result of both men’s mutual friendship and regard. Deakin’s close personal and political associations with many Labor figures stemmed from their respect for Deakin’s liberalism. Western Australian Senator George Pearce was not the only Labor man who ‘idolised’ Deakin.

But there were also crucial differences. From Deakin’s side, an indissoluble obstacle to formal coalition with Labor was his absolute rejection of the idea of Caucus control. With compulsory arbitration prominent in Labor’s platform, the introduction of the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill in July 1903 brought the party differences into sharp focus. The resignation of Minister Charles Kingston over Cabinet’s exclusion of seamen from the provisions of the Bill, and the Victorian railway strike in May 1903, sharpened electoral support for Labor.

In the second federal election, the first where women had the same right to vote as men, Labor increased its numbers. The 3 parties – Protectionists, Labor and Free Trade – shared almost equal proportions of seats in the parliament.

The first sitting of the new parliament began on 2 March 1904. Deakin was unable to gather the numbers 6 weeks later for a government amendment to the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. He resigned as Prime Minister on 27 April. The same day, the Governor-General, Lord Northcote, summoned Watson to form a government.

The Governor-General’s advice of Alfred Deakin’s resignation as Prime Minister, 27 April 1904. NAA: A6662, 237, p. 2

Sources

- Grassby, A and Sylvia Ordonez, The Man Time Forgot: The Life and Times of John Christian Watson, Pluto Press, Sydney, 1999.

- McMullin, Ross, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1991.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Governor-General’s Office – correspondence – concerning the fall of the Deakin government and forming the Watson government 1904, NAA: A6662, 237