The triumph of the historic first Australian Labor government was a qualified one – Labor did not have the numbers to implement key policies. 6 bills were enacted during the brief government of John Christian (Chris) Watson. All but 1 – an amended Acts Interpretation Act 1904 – were money bills. The significant legislative achievement of the Watson government was the advancement of the troublesome Conciliation and Arbitration Bill (passed later that year by the government of George Reid).

The first national Labor government

The first Labor government – and the first such national government in the world – was formed on 27 April 1904, when Watson and his ministers took their oaths of office. Following Westminster tradition, Watson chose his own Cabinet and allocated the ministerial portfolios.

The last page of a secret despatch from Australia’s Governor-General to Britain’s Colonial Secretary 23 April 1904, detailing circumstances that created the first Labor Prime Minister in the British Empire.

NAA: CP201/1, p. 4

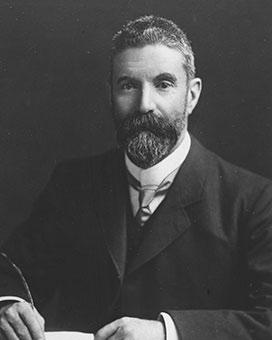

Watson, aged 37, was Australia’s youngest Prime Minister. Although previous prime ministers had taken the portfolio of External Affairs, Watson took the Treasury portfolio and allocated External Affairs to William Hughes. He gave Home Affairs to Egerton Batchelor, Trade and Customs to Andrew Fisher, Defence to Anderson Dawson and Postmaster-General to Hugh Mahon.

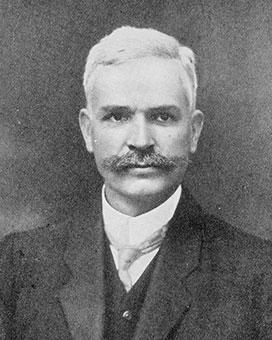

In another departure, Watson allocated the key portfolio of Attorney-General to a non-Labor member, Henry Higgins. Like Deakin, Higgins was respected by Labor for his reformist passion. Unlike the Protectionists, the Labor parliamentarians had few experienced legal professionals – their only lawyer was the very newly qualified William Hughes. The non-ministerial position, Vice-President of the Executive Council, Watson gave to Gregor McGregor, Labor’s leader in the Senate.

William Hughes later recalled the first meeting of the Labor Cabinet with characteristic sharp wit:

Mr Watson, the new Prime Minister entered the room, and seated himself at the head of the table. All eyes were riveted on him; he was worth going miles to see. He had dressed for the part; his Vandyke beard was exquisitely groomed, his abundant brown hair smoothly brushed. His morning coat and vest, set off by dark striped trousers, beautifully creased and shyly revealing the kind of socks that young men dream about; and shoes to match. He was the perfect picture of the statesman, the leader.

The fall of the Watson government

Despite the fitness of the new Prime Minister for his role, the government hung on the fine thread of Alfred Deakin’s promise of ‘fair play’. The ‘three elevens’ – the lack of a definite majority in the parliament after the second federal election – dogged Watson just as it had Deakin. His government was also defeated on the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill and Watson lost the prime ministership after less than 4 months in office.

Although Watson sought a double dissolution of parliament so that an election could be held, Lord Northcote, the Governor-General, refused. Unable to command a majority in the House of Representatives, Watson resigned, and his term in office ended on 18 August 1904.

Sources

- Crisp, LF, Australian Federal Politics and Law, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1956.

- McMullin, Ross, ‘John Christian Watson’ in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland Press, Sydney, 2001.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Photostat copy of secret despatch from the Governor-General to the Colonial Secretary 23 April 1904, NAA: CP201/1