Starting out

The youngest of 9 surviving children of William and Mary Louise Barton, Edmund Barton was born on 18 January 1849 in Hereford Street, Glebe, in Sydney. 2 years later, the Bartons moved to Cumberland Street in The Rocks, and when he was 7, 'Toby' Barton was enrolled at the nearby Fort Street Model School.

From the age of 10, Barton attended Sydney Grammar School in College Street, and met his lifelong friend Richard O'Connor. Twice dux of the school and school captain, Barton went on to an equally brilliant record at the University of Sydney. He was 19 years old when he graduated in 1868 with first class honours in classics.

Barton became a barrister in 1871. He was a sociable young man with interests ranging from the literary and scholarly to cricket and fishing, and he established a wide circle of friends during his twenties.

One of his fishing companions was George Reid, who took him along to the Sydney School of Arts Debating Society. There Barton's skills and confidence in public speaking were nourished and, in turn, the young barrister perhaps prompted Reid to study law.

During the 1870s Barton travelled through country New South Wales for court hearings – and for cricket matches and regattas. On an Easter cricket trip to Newcastle in 1870, Barton met Jane Mason Ross. In 1877, they married and settled in Sydney, where Barton's career turned from law to politics.

Barton's 20s were shaped by the colony's legal, social and sporting circles. In his thirties he moved readily between the spheres of the parliament and gentlemen's societies such as the Freemasons (he was initiated into the Australian Lodge of Harmony No. 556 in 1878) and Sydney's Athenaeum Club. Barton's family home was inconveniently located – he lived in a small house atop a steep hill in Manly. The house was isolated from the city once the last ferry crossed at 5pm.

On Macquarie Street

After two unsuccessful tries, Barton became a parliamentarian when he was elected to the University of Sydney seat in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in 1879. The following year, the University seat was abolished, and he won the rural seat of Wellington. In 1882, elected with Sir George Reid to East Sydney, Barton served as Speaker in the Assembly and became well known in the Macquarie Street Parliament House. According to the Bulletin, the youthful parliamentarians heralded 'the triumph of Young Australia'. Though only 33, Barton was a respected and successful Speaker for 4 years. Then with the influence of Henry Parkes, Barton was installed in the Legislative Council for the next 4 years.

From 1891 to 1894 Barton again represented East Sydney in the lower House, this time in opposition to Reid, the leader of the emerging Free Trade Party. Barton saw free trade as a fatal flaw for Federation – the issue divided New South Wales from Victoria, which supported protection of industry by imposing tariffs on imported goods. Barton abandoned free trade and stood on a protectionist platform against Reid.

From 1894 to 1897, Barton was out of parliament. He relied on his legal practice for income and to reduce the debts he suffered in the 1893 financial crisis. He returned to the Legislative Council in 1897 and, in 1898, having lost a contest with Reid for a Legislative Assembly seat, took the Hastings-Macleay seat in a by-election. This was the last colonial election he contested.

The 'one great thing' – Federation

Edmund Barton was a leading advocate of Federation, fired equally by Henry Parkes' speech at Tenterfield on 24 October 1889 and by Tasmanian lawyer and politician Andrew Inglis Clark. Barton's powerful speech to the Legislative Council on 8 October 1890 influenced New South Wales to participate in the national meeting proposed at the Australasian Federal Convention in Melbourne that year. Barton was subsequently nominated by the Council as a New South Wales delegate to the National Australasian Convention in Sydney in 1891.

Delegates at the National Australasian Convention in Sydney, 2 March – 9 April 1891, Daily Mail engraving. NAA: A6180, 30/11/83/23

His first address to the convention expressed a persuasive vision of a new nation:

I hope that I am at any rate acting in the spirit in which we all labour together, and that the result of our labour will be to found a state of high and august aims, working by the eternal principles of justice and not to the music of bullets, and affording an example of freedom, political morality, and just action to the individual, the state and the nation which will one day be the envy of the world.

3 years after Parkes' speech in Tenterfield on the Colony's northern border, Barton himself addressed large crowds in southern border towns and some fifteen Federation leagues were formed. In the winter of 1893, supporters organised a Federation conference at Corowa and, in 1896, a second 'people's conference' was held in Bathurst. Parkes died that year and Barton succeeded him as leader of Australian Federation.

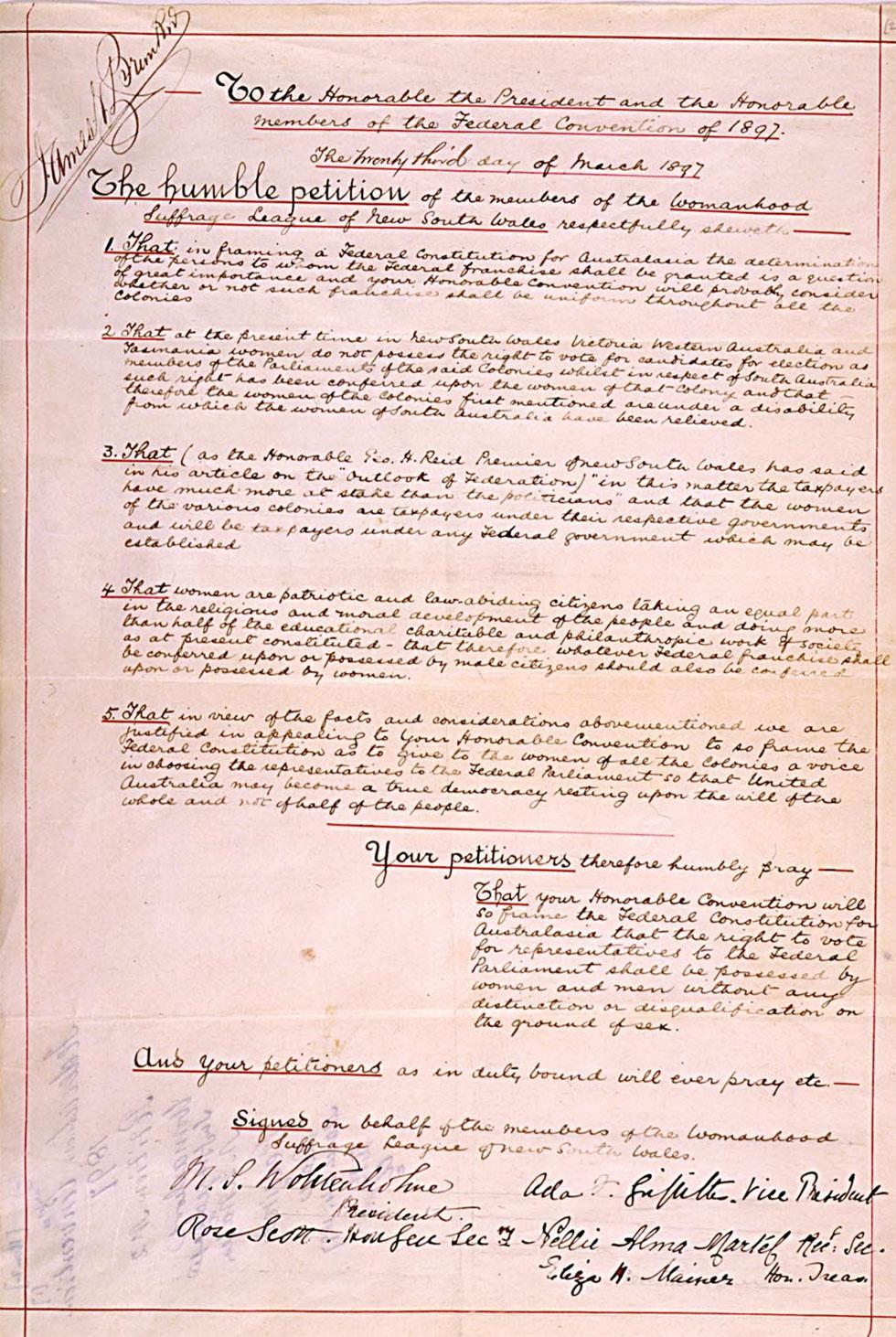

New South Wales Womanhood Suffrage League petition to the Australasian Federal Convention 1897. NAA: R216, 2

Each colony had prominent federationists and prominent opponents. Many of the organisations campaigning for women's right to vote were influential in the Federation movement and petitioned the constitutional conventions. Of the 6 colonies, only in South Australia could women voters use the ballot box to influence convention delegates. In every colony, there were federationists like Maybanke Wolstenholme, who were just as familiar to Sydney audiences as Edmund Barton, George Reid and Richard O'Connor.

Having topped the poll in the election of New South Wales delegates, Barton was elected president of the convention that met in Adelaide in March 1897, in Sydney in September 1897 and in Melbourne from January to March 1898.

The drafting committee for the Australian Constitution Bill in Adelaide in 1897. Left to right: John Downer, Edmund Barton and Richard O'Connor. NAA: A1200, L16929

Parkes had complained to Barton that his country tour in 1892, and the conferences at Corowa in 1893 and Bathurst in 1896, only delayed the legal steps for enacting a federal constitution. Barton replied, 'I am enlisting the people. Can you do without them?' His response affirmed the process of creating the new nation by popular vote. First the Constitution Bill was agreed by the convention delegates elected by each colony in 1897. Then it was debated in each of the 6 colonial parliaments. When each parliament passed the Bill, it faced six more hurdles – final referendums of the voters in each colony, held between June 1899 (New South Wales) and July 1900 (Western Australia).

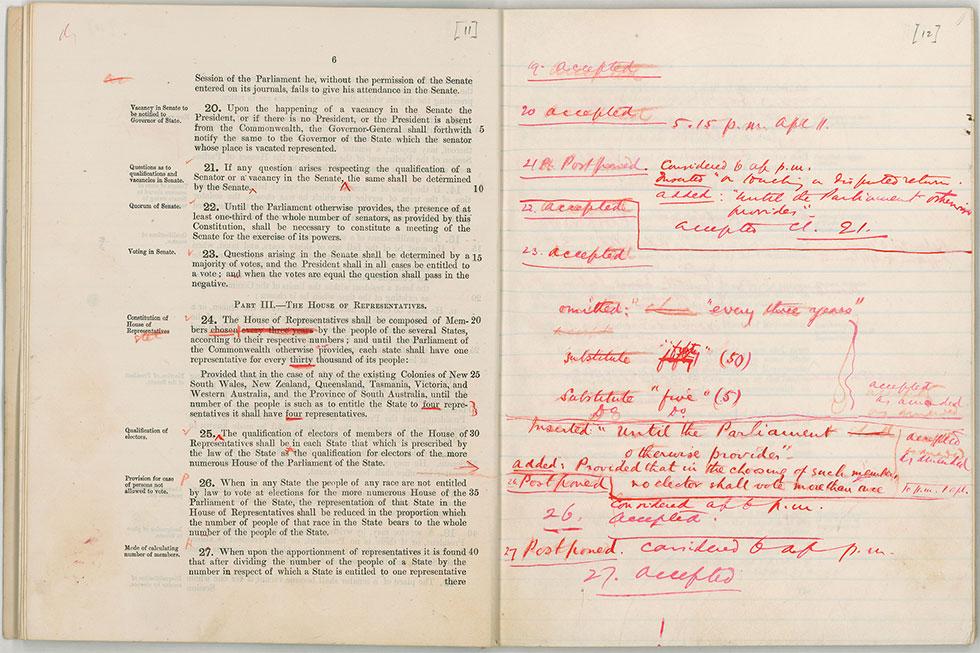

Edmund Barton’s 1897 notebook showing comments on the 1891 draft of the Australian Constitution. NAA: R212, 1

The final steps were approval by the British parliament and assent of the Queen. In March 1900, Edmund Barton, Alfred Deakin, James Dickson, Charles Cameron Kingston and Philip Fysh formed a delegation to London representing all the colonies except Western Australia (which did not hold its Federation referendum until 31 July that year). For 3 months, they lobbied for the successful passage of the Bill through the House of Commons and the House of Lords. On 9 July 1900, the Bill was enacted, and on 17 September Queen Victoria proclaimed 1 January 1901 the date the new nation would be born.

The 'Hopetoun blunder'

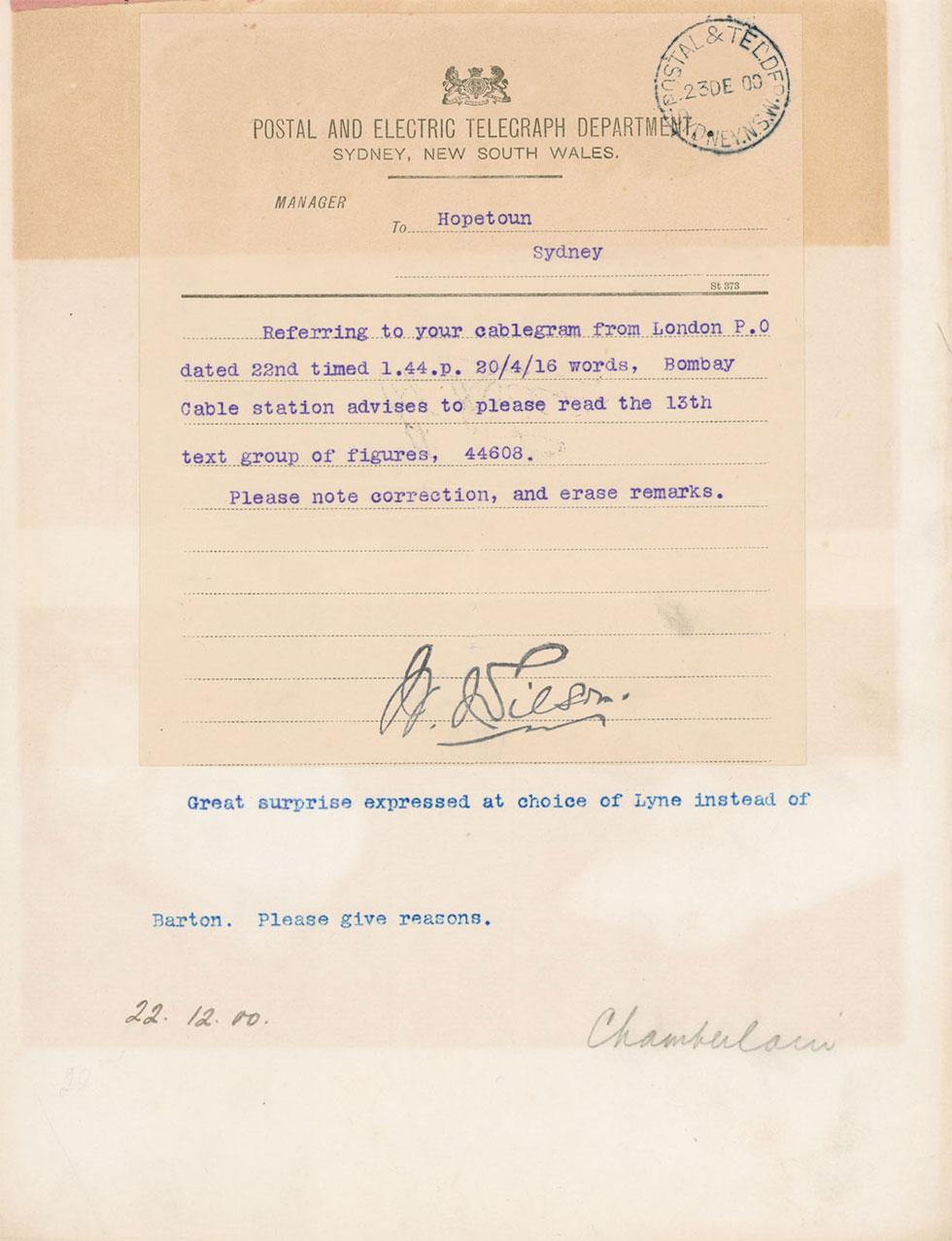

4 days after he arrived in Sydney, the Governor-General designate, Lord Hopetoun, named New South Wales Premier William Lyne as the first Prime Minister. Lyne had opposed Federation, and this unfortunate decision was unacceptable to the leading federationists, whose choice was Barton. After tense negotiations from 19 December, and a 'please explain' telegram from the British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, Lyne stood aside. On Christmas Eve, Hopetoun named Barton instead.

Joseph Chamberlain's telegram to Lord Hopetoun on 22 December 1900 asking for an explanation of the problem with the selection of Sir William Lyne as the first Australian Prime Minister. NAA: A6661, 1055, p. 3

On Christmas Day, Barton announced the first Commonwealth ministry. Drawn from each colony, the ministers were:

- Alfred Deakin (Attorney-General)

- George Turner (Treasurer)

- Charles Cameron Kingston (Minister for Trade and Customs)

- John Forrest (Postmaster-General)

- James Dickson (Defence Minister)

- Sir William Lyne (Minister for Home Affairs)

Richard O'Connor and Neil Lewis were named honorary ministers without portfolio.

Sources

- Bolton, Geoffrey, Edmund Barton, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2000.

- Deakin, Alfred, The Federal Story, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1963.

- La Nauze, JA, The Hopetoun Blunder: The Appointment of the First Prime Minister of Australia, December 1900, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1957.

- Souter, Gavin, Lion and Kangaroo: The Initiation of Australia 1901–1919, William Collins, Sydney, 1976.

From the National Archives collection

- Records of the Australasian Federal Convention, 1897–98, petition, NAA: R216, 2

- Records of the Drafting Committee, Australasian Federal Convention, 1897–98, Barton's notebook, NAA: R212, 1

- Telegram from Secretary of State for the Colonies, 1900, NAA: A6661, 1055