‘Our new and terrific task’ – creating the Commonwealth

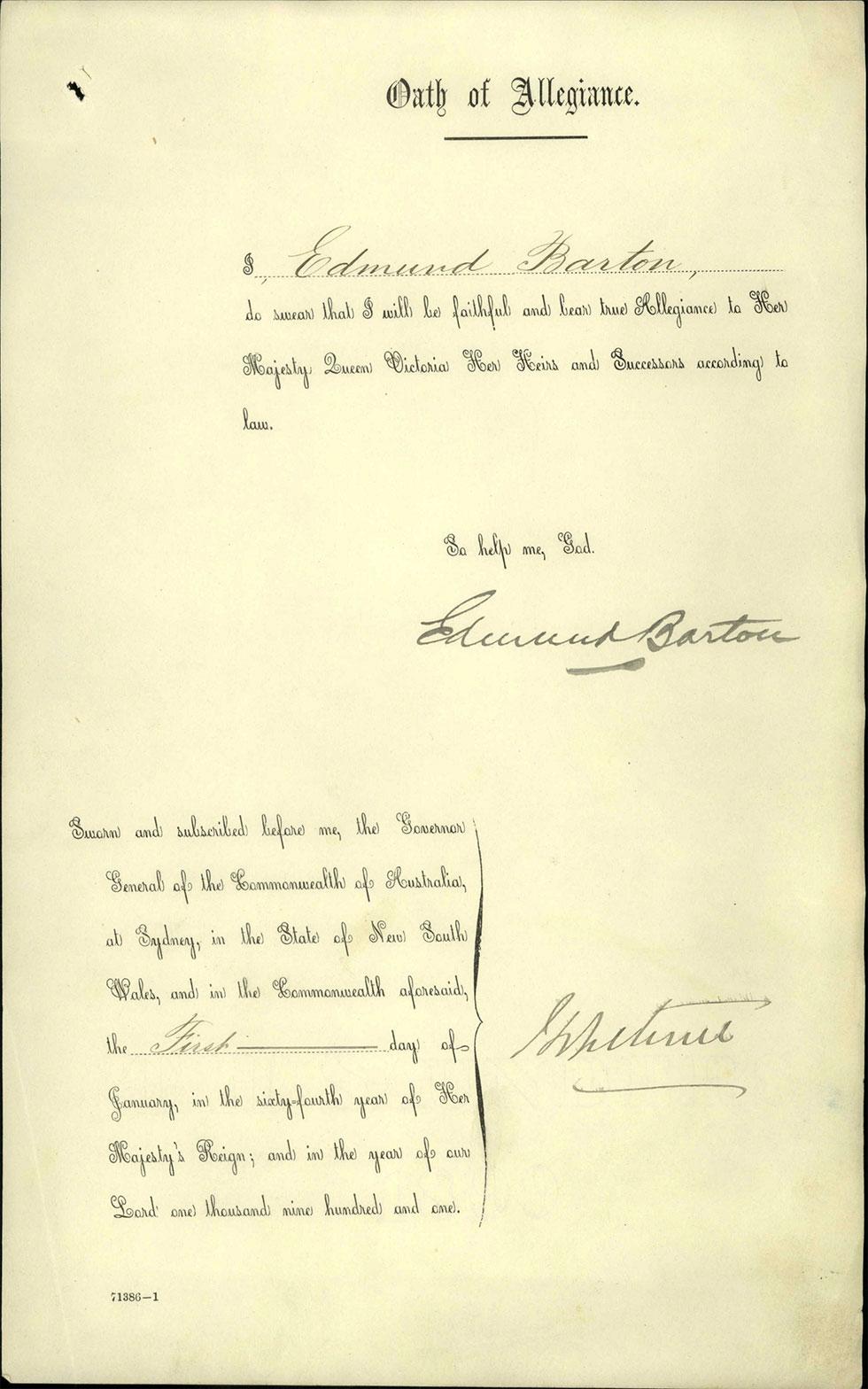

The Commonwealth of Australia was born soon after midday on 1 January 1901, when the Governor-General read out the documents signed by Queen Victoria to the 200,000 people assembled in Sydney’s Centennial Park and took his oaths.

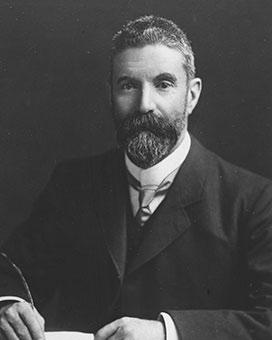

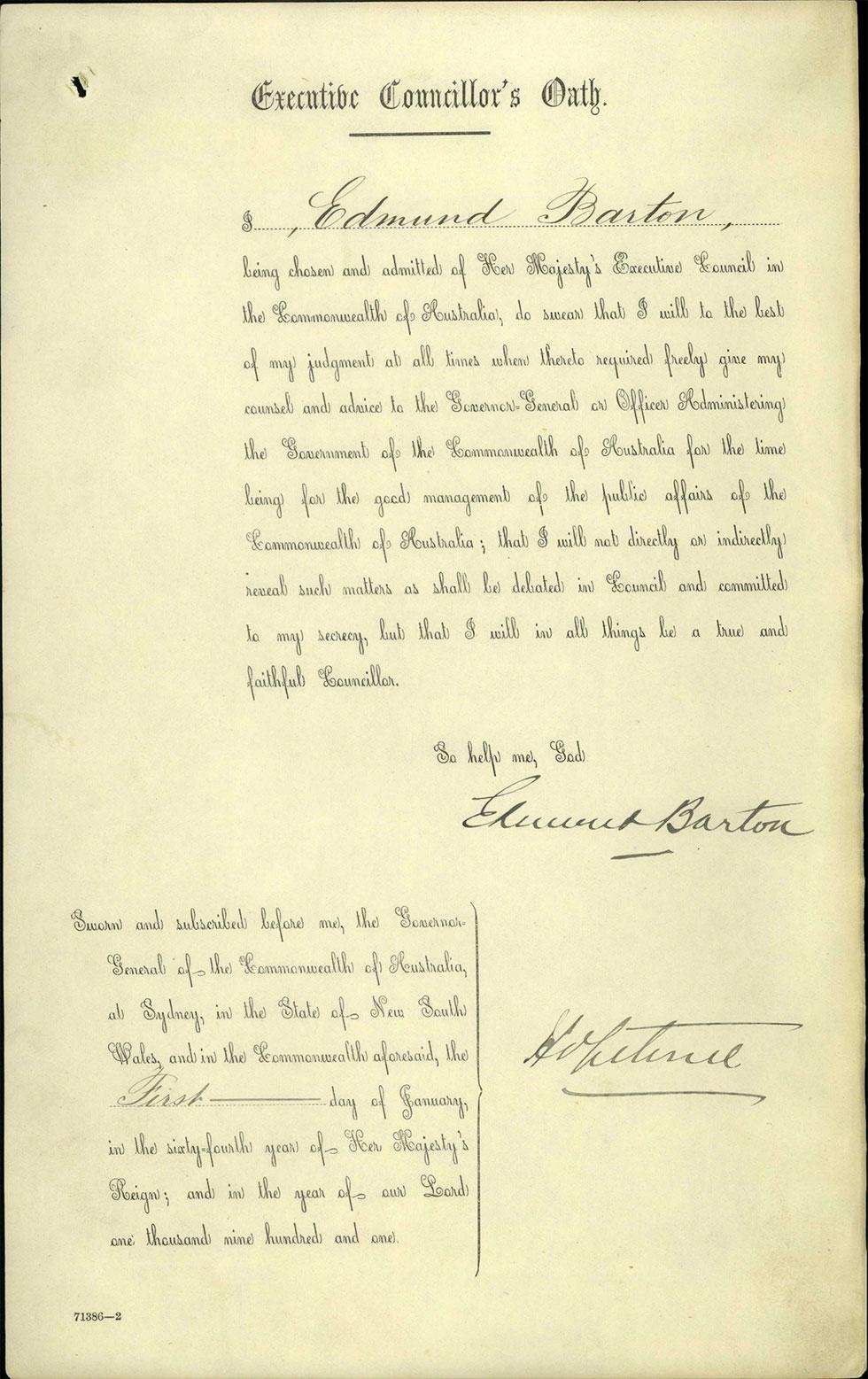

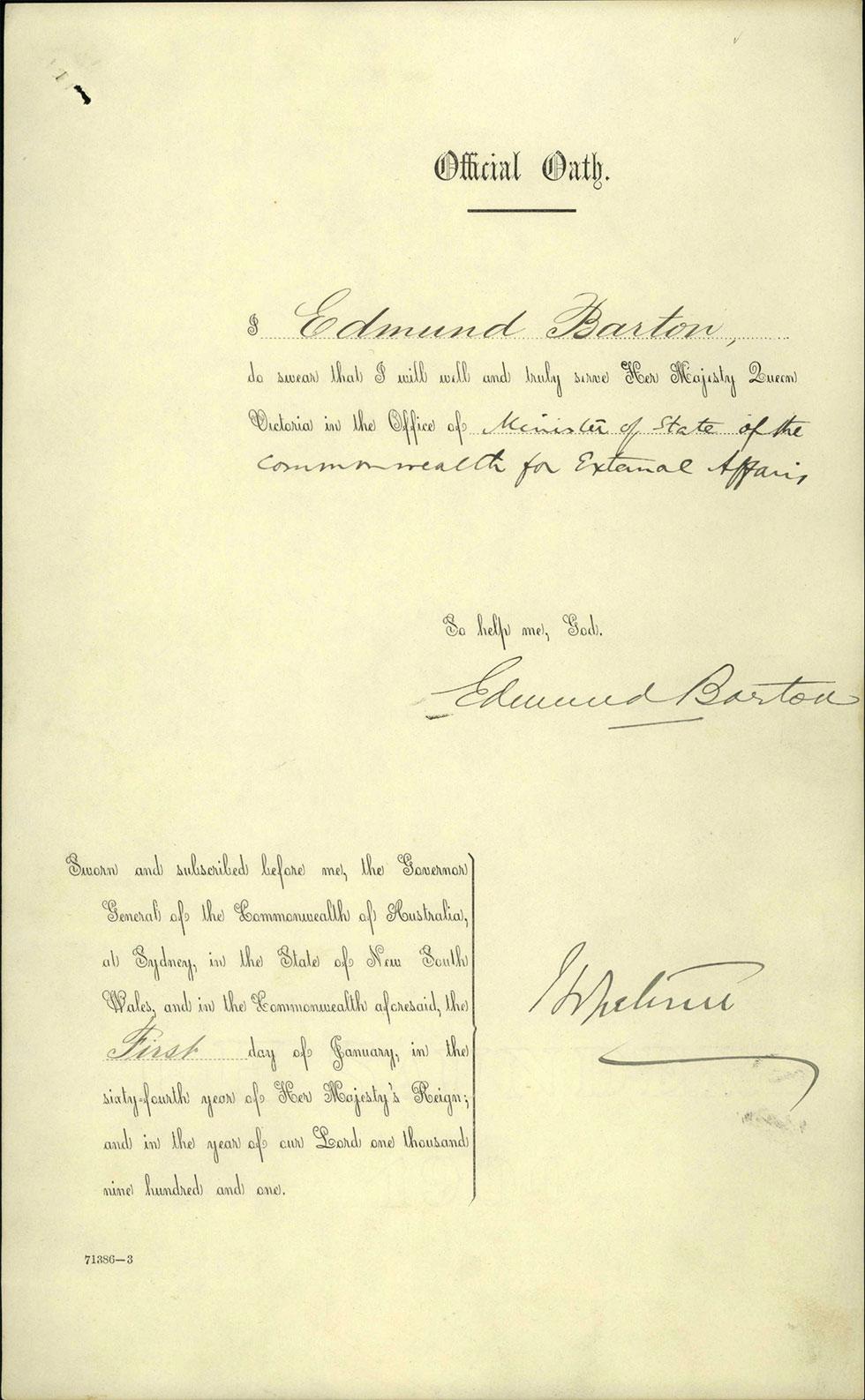

Edmund Barton's Oath of Allegiance, Executive Councillor's Oath and Official Oath, sworn on 1 January 1901. NAA: A5447, 1, p. 6

Page 2 of Edmund Barton's Oath of Allegiance, 1 January 1901. NAA: A5447, 1, p. 7

Page 3 of Edmund Barton's Oath of Allegiance, 1 January 1901. NAA: A5447, 1, p. 8

The new nation was vast. The 5 states stretched across a continent of 7.5 million square kilometres, with the 6th state the island of Tasmania. Australia’s population was tiny in comparison with most other nations, with only 3.8 million non-Indigenous people in 1901. Barton and his 8 ministers started a government with no parliament, no public service and no accommodation. The Prime Minister’s first office was a borrowed room in Sydney’s Parliament House. His secretary, Arthur Hunt, worked from a makeshift desk in a hallway.

On 10 January, Barton had his first Cabinet reshuffle when the sudden death of James Dickson meant John Forrest took the Defence portfolio and James Drake joined the ministry as Postmaster-General. The immediate tasks were setting up the basic machinery of government and arranging to hold the first federal elections 3 months later.

The first parliament

Barton’s government was returned at the March elections, with the only change in Barton’s ministry being Philip Fysh who replaced fellow Tasmanian Neil Lewis. The next step was the opening of the first parliament on 9 May 1901. Victoria’s state parliamentarians vacated their Parliament House to provide the temporary home – for the next 26 years – of the federal parliament. Not only was Barton’s office located in the Spring Street building, but so were his lodgings – a small attic space where he slept, and sometimes provided impromptu suppers for his Cabinet ministers.

The first parliament made laws ranging from the 3 tariff acts for raising revenue, to the far-reaching policy agenda Barton had set out during his election campaign. Among the first new laws debated were bills to exclude Pacific Islanders, Asian people and others in order to make the new nation a ‘White Australia’. Both the Pacific Island Labourers Bill and the Immigration Restriction Bill were passed shortly before parliament rose for the first Christmas recess, and enacted when the Governor-General assented to them, the former on 17 December 1901 and the latter a week later. This became known as the White Australia Policy.

The following year, the law granting women the vote on the same basis as men was enacted. Though not a supporter of women’s suffrage, Barton acquitted his part of the bargain with the suffrage organisations – the vote in national elections in return for their support for Federation.

One of the problems the government wrestled with was the shortfall between the allowances parliament allocated the Governor-General and Lord Hopetoun’s actual expenditure in his first year of office. There was a difference in the government’s idea of the scale of the functions of the office, and Lord and Lady Hopetoun’s view of what was necessary, particularly in the year of a Royal visit. With another vice-regal prospect waiting in the wings, no middle ground was found. In 1902, South Australia’s Governor, Lord Tennyson, became Australia’s second Governor-General.

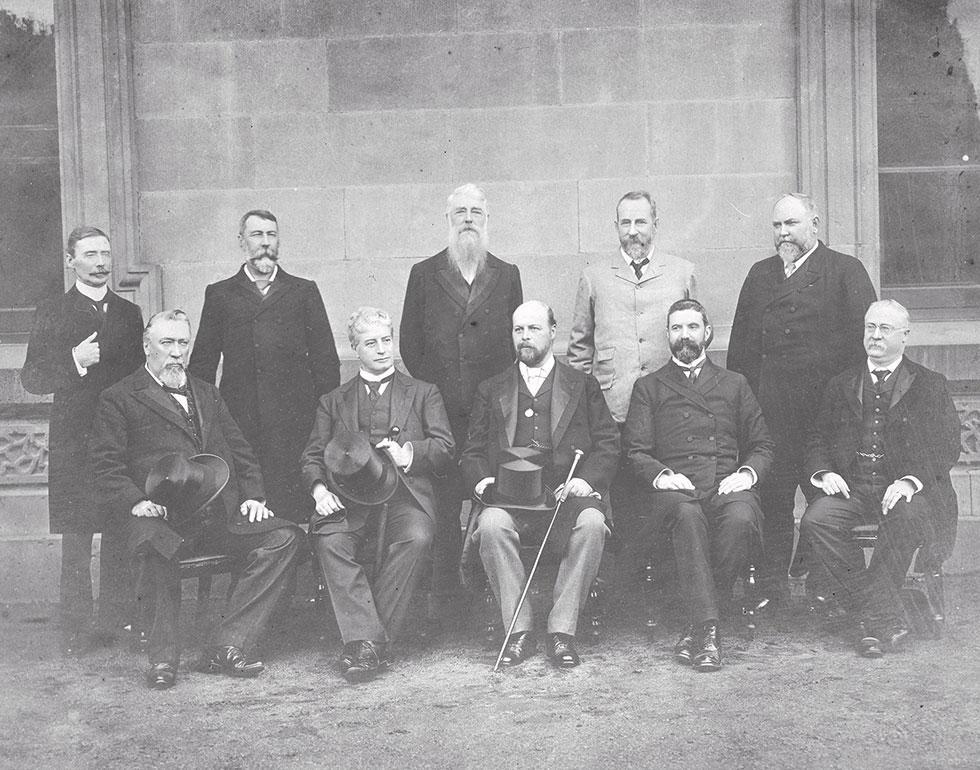

Executive Council 1902 – the ministry of Edmund Barton in 1901, showing the following members of the first federal Cabinet: standing (left to right): James George Drake, Richard O'Connor, Philip Fysh, Charles Cameron Kingston, John Forrest; seated (left to right): William John Lyne, Edmund Barton, Lord Tennyson (Governor-General), Alfred Deakin and George Turner. NAA: A1200, L13365

The term of the first parliament was 17 months, from May 1901 to October 1902. In this period, there were 220 sitting days in the House of Representatives and 178 in the Senate. 59 acts were passed, mostly setting the legal, financial and administrative foundations of the Commonwealth, as provided for by the Constitution. For the last third of this period, Barton was overseas and Alfred Deakin was acting Prime Minister. Despite this, Barton held the record for length and frequency of speeches in the House of Representatives. The only person to occupy more columns in the Hansard record of the debates in the first parliament was his oldest friend, Senator Richard O’Connor.

A ‘reasonable imperialism’

Edmund Barton became the Prime Minister of a nation at war. Volunteer forces from the colonies had been fighting in South Africa since Britain had declared war in October 1899. At the end of his first year in office, Britain sought additional troops from the new Commonwealth and Barton secured the parliament’s agreement. By the time the ‘Bushmen's Contingent’, the first Commonwealth force, arrived in South Africa, the war was in its closing phase and ended on 30 May 1902.

By then Barton, accompanied by Jane Barton and Austin Chapman, was on his way to London to represent the Commonwealth at the coronation of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, in June 1902, and at the Imperial Conference to follow. Lord Hopetoun had recommended Barton for the highest order of knighthood available and, in the coronation honours list, Barton was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Michael and St George (KCMG).

Among the many presentations to the Prime Minister on this visit was one to acknowledge the assistance given by Australian women in the long fight for votes for women in Britain. Barton later gave the framed address, given to him by the suffragette leaders, to Sydney feminist Rose Scott.

The Bartons had an intensive round of engagements during their summer in Britain. While the coronation on 9 August was the focus, many other events were of more direct concern for Australia. Among the most important was the 10-year agreement Barton negotiated for the nation’s contribution to the upkeep of an expanded British naval squadron at Sydney, in return for training of a local naval reserve. His arguments also achieved an implicit protectionist recognition of the link between Australia’s revenue from imperial trade and Australia’s ability to resource defence and other services provided to the empire. This was the first shot in Australia’s long campaign for preferential trade within the empire – a policy refrain of Australian prime ministers until Britain turned to its geographic neighbours and joined the European Economic Community in 1973.

One of Barton’s final challenges as Prime Minister was to forge parliamentary support for the Anglo–Japanese naval agreement introduced in July 1903. In May and June that year, 3 Japanese warships marked Britain’s alliance with Japan by including the ports of Adelaide, Melbourne and Hobart, and the Sydney naval base, in a training cruise. In arranging the colourful celebrations highlighting the visit, Barton ordered the invitations to be ‘1000 times sweeter than sugar’ and the visiting admiral, officers and sailors were welcomed as ‘not strangers, but allies and friends’ of Australians. 18 months later, Australia’s role in implementing the Anglo–Japanese alliance was recognised when the Japanese government awarded both Edmund Barton and Lord Tennyson the Order of the Rising Sun First Class, still the highest honour Japan accords foreigners.

Unfinished Federation business

Barton’s tactical skills and his ability to shape consensus gave the government a full term in office to begin building the constitutional blueprint. This blueprint, and the policy issues distinguishing the Protection, Free Trade and Labor parties, opened national debate on issues covering relations with Britain, a ‘White Australia’, defence, the tariff questions, the High Court, old age pensions, Commonwealth–State relations in finance and industrial matters, and federal responsibilities for railways including the proposed east–west transcontinental railway.

Some constitutional matters, such as the federal conciliation and arbitration role, and the provision for establishing a permanent location for the seat of government, remained unsettled as parliament geared up for the election due in its third year. Neither of these matters would be resolved easily.

Among the most pressing business in the last session of the first parliament, from May to December 1903, was legislation to establish the High Court as provided in the Constitution. The Judiciary Act 1903, enacted on 25 August 1903, established the Court with 3, rather than the 5 judges originally proposed.

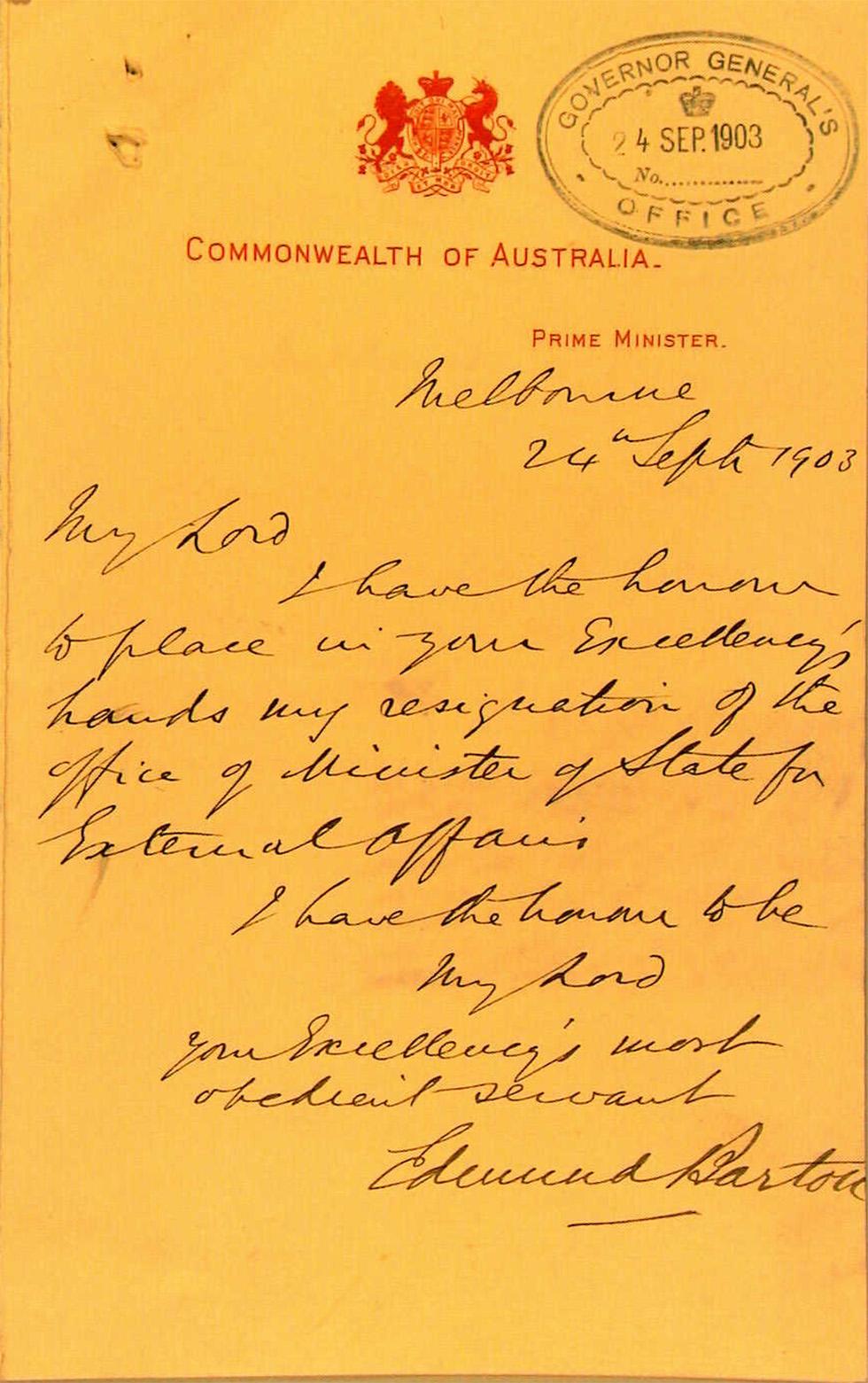

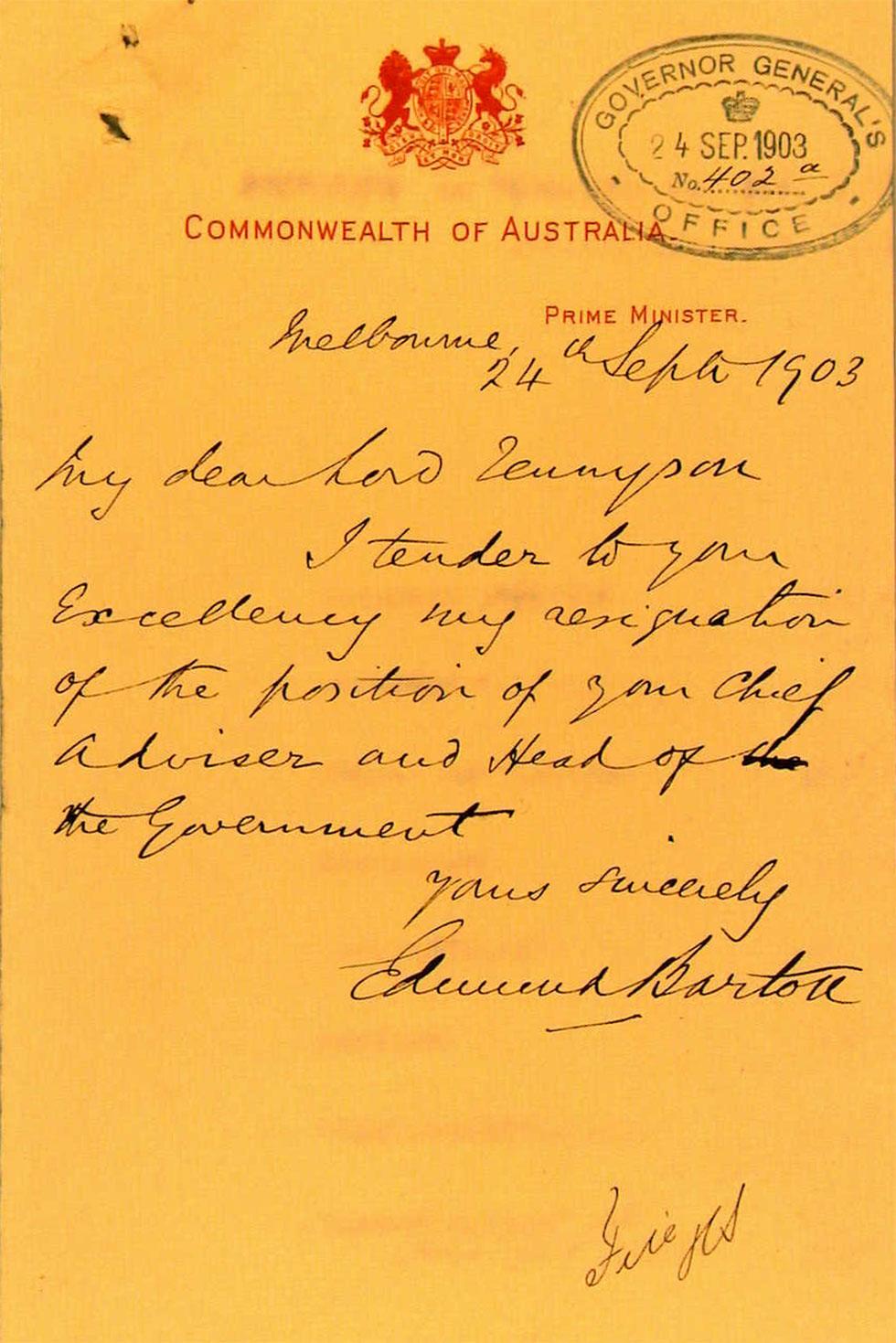

Barton’s term as Prime Minister ended before the first parliament did. His last speech in the House was on 23 September 1903. The next day he informed Cabinet that he and Richard O’Connor would accept appointment to the new High Court. That afternoon, Barton tendered his resignation as Minister for External Affairs and as ‘the head of government and your chief adviser’ to the Governor-General.

Edmund Barton's resignation as Minister of External Affairs and Head of Government on 24 September 1903. NAA: A5447, 2, p.6

Page 2 of Edmund Barton's resignation on 24 September 1903. NAA: A5447, 2, p.7

The parliament Barton had led included 6 future prime ministers, as well as Isaac Isaacs who, 30 years later, became the first Australian-born Governor-General. The qualities that made Barton leader of the Federation movement were evident in his role as the nation’s first head of government. He led a Cabinet of experienced and able ministers, many of them former colonial premiers.

His failings were no secret. Even his close colleagues, like Alfred Deakin or Arthur Hunt, commented on serious flaws such as Barton’s inattention to detail and lack of punctuality. A self-indulgence that made it difficult for him to address habitual behaviours like these also led to much-publicised periods of drinking and dining. Notorious newspaper editor John Norton even dubbed him ‘Toby Toss-Pot’.

Like many of his contemporaries, Barton envisaged a democracy of equals, not the equality of all to govern. That all are equal before the law was a fundamental tenet to Barton as barrister, politician and judge. But to him, and to most of his legal and parliamentary colleagues, this did not mean that all were equal to the responsibility of making the law.

As Australia’s ‘prime’ minister – the first to fill the role – Edmund Barton is now known as the man who by worthy example, led the way for a new nation. But looking back at the nation’s first century, Barton has a place among the first rank of Australia’s Prime Ministers, if only for his ability to glimpse, pursue and secure ‘one great thing’, the founding of Australia as a nation-state.

Sources

- Bolton, Geoffrey, Edmund Barton, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2000.

- Cuneen, Chris, King’s Men: Australian Governors-General from Hopetoun to Isaacs, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1983.

- Keenan, JJ (comp.), Inaugural Celebrations of the Commonwealth of Australia, Government Printer, Sydney, 1904.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives collection

- First Commonwealth ministry, Barton ministry 1901–03, ministerial oaths, NAA: A5447, 1