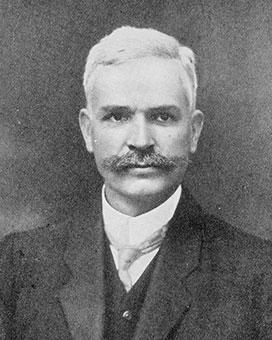

A democrat and reformer, Reid was an influential liberal before and after Federation. His role in New South Wales politics was similar to Alfred Deakin’s in Victoria.

In fact, however, these 2 men were startlingly different – in background, manner and tastes. There were profound differences, not only in their prime ministerships, but in liberal thought in the nation’s founding years.

George Houstoun Reid was a Scot, born on 25 February 1845 at Johnstone, Renfrewshire. He was the fifth of 7 children born to Marian Reid and John Reid, a Presbyterian minister. In May 1852, the Reids were among the hundreds of people who arrived in Melbourne during the goldrushes.

Reid went to school at the Melbourne Academy (later Scotch College). As in Scotland, the family’s fortunes were indifferent. In 1858, his parents moved with their 3 youngest children to Sydney, and 13-year-old George Reid started work as a clerk in a city merchant’s ‘counting house’.

‘Young Australia’ 1860–84

Reid remembered his first job as a great liberation from formal schooling, and the point when his education really began. He enthusiastically sought the ‘self-improvement’ opportunities Sydney offered. At the age of 15, he joined the School of Arts Debating Society, where democratic reforms such as manhood suffrage were passionately argued.

Reid was among the most eloquent and ardent members of the Society throughout his 20s and recruited, among others, Edmund Barton and Richard O'Connor. Places like the Society’s Pitt Street rooms enabled these young men to make contacts essential for their advancement. In the case of Barton and O’Connor, the Society added to the opportunities offered at school and university.

Reid’s drive and intelligence attracted essential connections, and he developed an easygoing and cheerfully impervious amiability. This characteristic was to make him a key parliamentary player – fast with a retort and rarely harbouring resentments. It brought him the criticism of deeper thinkers and more polished stylists, and also the warm response of voters.

Reid was a young man with a plan. At the age of 19, he went from the counting house to the rapidly growing public service. He first gained a post in the New South Wales Treasury and progressed to chief branch clerk. By 1878, aged 33, George Reid headed the Attorney-General’s department.

By then, he had published three notable works on political questions. His 1873 pamphlet The Diplomacy of Victoria on the Postal Question argued the New South Wales case for extending the route of mail steamers to Sydney, as the terminus was Melbourne. Five Free Trade Essays, 2 years later, compared the effects of protective tariffs in Britain, the United States and Victoria. It was a controversial book that earned Reid honorary membership of London’s Cobden Club.

The third work, his book An Essay on NSW, Mother Colony of the Australias, was part of the colony’s contribution to the grand exhibition in the United States to celebrate the 1876 centenary of the signing of the US Declaration of Independence.

But throughout the 1870s George Reid had his eyes, if not always his attention, on qualifying as a barrister. For him, the law was the only real path to politics – the means of earning a living since parliamentarians were unpaid. Within a year of his admission to the Bar on 19 September 1879, he had resigned from the public service so as to be eligible to nominate as a candidate for East Sydney.

In November 1880, Reid arrived, taking a seat in the Legislative Assembly in Macquarie Street for the first time. He held this seat for the next 20 years. A brief gap in 1884–85 marked the only electoral loss in a career that spanned 40 years and 3 legislatures.

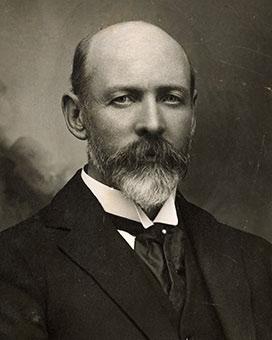

Reid’s friend, Edmund Barton, had entered the Assembly the year before. Barton’s path, however, was rather more direct. 4 years younger than Reid, Barton had starred at school and university, and gained admission to the Bar at 22, in 1871. That year, Reid began to work towards the legal qualification which he finally achieved in 1879.

When both men were returned for the East Sydney seat in 1882, the Bulletin hailed them as the men of the future, as ‘young Australia’. Barton was then 33 and Reid 37. The accolade saluted their clashes with Henry Parkes and other established figures. Both were persuasive in parliament and effective campaigners outside, but it was Reid who consistently topped the East Sydney poll.

The only electoral loss of Reid’s career was in 1884, when he was unseated in a by-election. It was the only time his redoubtable popularity did not rise above all else for those whose interests he represented.

‘A parliament man, not a party man’ 1885–90

A strong and, unlike Barton, unshakeable supporter of free trade, Reid’s personality, politics and principles made him an electoral winner in a strongly free trade colony. He was an influential liberal who energetically promoted public education and public libraries. He also worked for reform of the civil service and appointment on merit rather than patronage.

Despite the ensuing loss of a ready source of revenue for the government, Reid was committed to reform of the ‘selection before survey’ land laws which had promoted fraud and malpractice.

Unattached to any of the multiple shifting factions that dominated colonial parliaments, Reid declined to join Henry Parkes’ ministry. He continued his support of the Parkes government, but retained his independence to argue against specific legislation and policies inside and outside the parliament. Reid’s liberal principles meant he was vigorously opposed to the Chinese Immigration Restriction Act 1889, supported by the labour movement as well as by many of his free trade colleagues.

In 1889, Reid was a founder of the Free Trade and Liberal Association of New South Wales. Together with the opposing Protectionist Union and the Labour Electoral League, it became one of the three political parties that dominated the last colonial decade and the first 10 years of Federation.

Federation fathers 1891–94

Though a supporter of Federation in principle, Reid was suspicious of the rapid embrace of Federation by Henry Parkes and Edmund Barton. His judgement was reinforced when Barton abandoned free trade, seeing it as a barrier to achieving agreement with the other 5 colonies, and became a Protectionist. After the Australasian Federal Convention in March–April 1891, Reid voiced strong opposition to the constitution drafted at the convention. He argued that it undermined the colony’s free trade policies, and that increased financial power for the proposed lower House and a less powerful Senate were vital.

In November 1891, 6 months after the convention, 46-year-old Reid was elected leader of the Free Trade Party, and became Leader of the Opposition in the New South Wales parliament. Reid had just returned from a brief honeymoon, after his wedding on 5 November at the Presbyterian manse in Wangaratta, Victoria. His bride, 21-year-old Flora Brumby, was already acquainted with Sydney’s political circles as she was a friend of Bernhard Wise. Despite this, and Reid’s own prominence, the marriage remained secret until a small announcement in the Town and Country Journal in August 1892. The couple’s first child, Thelma, was born the following year.

By then, Reid’s friend of 20 years, Edmund Barton, was the father of 5 young children. Both men faced difficulty in the 1890s economic downturn, attempting to earn a living at the Bar to support parliamentary careers and families. Despite their early friendship, their politics had diverged over the Federation strategy and they had become unlikely companion candidates in the East Sydney seat. In 1893, the Assembly adopted single-member seats and abandoned plural voting, and they were then in competition for the seat.

At the July 1894 election, Reid roundly defeated Barton, who had been out of parliament for 3 years. In contrast, Reid became Premier and led the government of New South Wales for the next 5 years. Among his ministers was former Labor Party member Joseph Cook, now a Free Trader.

In May 1897, Flora Reid and their small children Douglas and Thelma, farewelled George Reid at Port Adelaide as his ship took him on a 4-month visit to England for Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee and the Imperial Conference. He disembarked at Naples, to travel in style to Rome, Florence, Milan, Lucerne and Brussels, before embarking at Ostend for London.

As Premier, Reid had become a key figure in the revival of Federation. At the Bathurst ‘people’s convention’ in 1896 he committed himself to bring Queensland into the union. On his London visit, he met with Joseph Chamberlain, Britain’s Colonial Secretary, to report on the progress of Federation and, with the other five premiers, was made a Privy Councillor.

Reid returned soon after the opening of the 1897–98 Federation convention in Adelaide to take up his role as delegate. He had polled second to Edmund Barton among the New South Wales delegates. For Barton, Federation came first; for Reid, New South Wales was the primary concern – Federation of the colonies must be in the colony’s interests.

‘Not a hand worth holding’

The difference in the approaches of Barton and Reid to Federation was clear in Reid’s speech on 28 March 1898. He told a large public meeting that he would vote for the Constitution Bill and Federation, but listed the reservations he considered all New South Wales voters should weigh in making their own decisions at the June referendum. For this conscientious and, perhaps, calculated position, Reid earned the distrust of many fellow federationists, most notably Barton and Alfred Deakin. When the Bill failed to gain the minimum affirmative vote (set by Reid’s government) at the New South Wales referendum, he was dubbed ‘Yes/No’ Reid. Barton, Deakin and other Protectionist federationists already regarded him as wily and shrewd; they now considered him devious and a danger to Federation.

The Federation impasse was resolved at a ‘secret’ premiers’ conference at Melbourne’s Windsor Hotel, opposite the Spring Street Parliament House, held over six days from 29 January 1899. The compromise clause proposed by Tasmanian Premier Edward Braddon meant the Commonwealth must return to the States a proportion of all tariff and duties, which Reid persuaded the other Premiers to limit to the first 10 years after the Commonwealth's establishment. To Reid’s satisfaction, the ongoing battle between Victoria and New South Wales over the siting of the national capital was also settled. Under the compromise, the site would be in New South Wales, but not less than 100 miles (161km) from Sydney.

Reid had forfeited the support of suffragists, whose intensive campaign during his premiership met with continued stonewalling. Both those opposing the Constitution Bill like Rose Scott, and supporters like Maybanke Anderson, had found more fruitful ground in petitioning the Federation convention than in lobbying Reid, despite his liberal democratic principles. They presented a petition to the Adelaide session of the convention through the acting Premier, John Brunker, before Reid returned from London.

With women still prevented from voting, New South Wales voters approved the amended Constitution Bill on 20 June 1899. With a reduced majority after the July 1898 election, Reid’s government depended on an alliance with Labor leader William Holman. As the Bulletin observed, he then saw Labor as ‘a hand worth holding’. Reid was just as opposed to Labor’s caucus solidarity principle as his minister, Labor defector Joseph Cook, so this was not a secure arrangement. Moreover, though Reid had again trounced Barton in East Sydney in the July election, Barton secured the Assembly seat of Hastings-Macleay in a subsequent by-election and was now Leader of the Protectionist Opposition.

After the intrigues involving Barton, Labor’s WA Holman and William Hughes decided the alliance with Reid was at an end. Unable to secure a double dissolution from the Governor, on 13 September 1899 Reid resigned in recognition of the forces combined against him. Not least of these was the sectarianism his even-handed approach had failed to quell.

‘The most ungrateful excommunication’

Losing the premiership deprived Reid of a hope of becoming Australia’s first Prime Minister. Deakin thought Reid capable of the revenge of devising ‘the Hopetoun blunder’, when the Governor-General designate named William Lyne, not Barton, as Prime Minister in December 1900.

In the absence of any evidence of Reid’s involvement, this remains supposition, particularly as there is little evidence of Reid having a thirst for revenge throughout 40 years of public life. On the other hand, it is fact that Barton excluded Reid from his first ministry. Pointing out that Reid had a far stronger claim than half the men included, historian LF Crisp referred to this as ‘the most ungrateful excommunication’.

Early in 1900, while Barton and Deakin were leaving for London to ensure the passage of the Constitution Bill through the British parliament, Reid launched his federal election campaign. An intercolonial free trade conference in February began an ‘energetic journeying’ around Australia to promote Free Trade policies and prepare the way for Free Trade candidates.

Even without the advantage of a role in government from 1 January 1901, in the March election Reid worked his platform magic and was returned for the new federal electorate of East Sydney.

Leader of the Opposition 1901–04

Among the Sydney-siders elected to the first parliament were 5 of Australia’s first 7 prime ministers. All had been founders of the 3 parties in New South Wales:

- Edmund Barton (Protectionist)

- George Reid (Free Trade)

- Chris Watson, Joseph Cook and William Hughes (Labor)

The Free Trade parliamentarians included 3 other former premiers:

- Edward Braddon and Henry Dobson from Tasmania

- Vaiben Solomon from South Australia

Protectionists prevailed in Victoria, so the Free Trade representatives bore an additional burden of time and expense in travelling to Melbourne and establishing accommodation. Reid and four fellow Free Traders shared the costs of renting a furnished house in St Kilda, and did the necessary entertaining very modestly there.

Even so, Reid was less than rigorous as Leader of the Opposition. He was frequently in Sydney during sitting weeks, anxious to rebuild his law practice. As deputy leader, William McMillan took Reid’s place on more than half of the 164 sitting days in the parliament’s first year.

Reid was in the House often enough to preserve his reputation for quick and witty rejoinders and persuasive debate. A key issue for the first parliament was establishing the import tariffs, the main source of revenue for the Commonwealth. For the Free Trade Party this posed a dilemma. Delay of the inevitable was their only course of action.

When the Treasurer tabled the tariff proposals on 8 October 1901, Reid made history by moving the parliament’s first censure motion. This strategy set in train 8 months of ‘frittering struggle over details and a shameless repetition of stock fiscal arguments’, as Deakin described the ‘nightmare’ of the prolonged debate in June 1902. When the first parliamentary session ended on 10 October, the most contentious of the four tariff measures had finally become the Customs Tariff Act 1902. This was achieved to the exhaustion of all, particularly Deakin, the acting Prime Minister during Barton’s 6 months in London that year.

The new Governor-General, Lord Tennyson, opened the second session of the nation’s first parliament on 26 May 1903. Under attack from Reid, Leader of the Opposition, and Chris Watson, Leader of the Labor Party, the Barton government was immediately embroiled in debate over the Conciliaton and Arbitration Bill and the Papua (British New Guinea) Bill.

The latter was necessary for the acceptance of Britain’s New Guinea as a Commonwealth territory, and the establishment of an Australian administration there. When Labor attempted to amend the Papua Bill so that the proposed Papua Legislative Council would be elected by the white population, Reid argued for the ‘just rights of the blacks’.

A shrewd strategist as well as a persuasive debater, Reid made another historic gesture when he resigned his seat on 18 August 1903 to protest the Protectionist government’s rejection of the Electoral Commission proposal for an additional Sydney seat. This was part of the redrawing of electorate boundaries for the second federal election. Reid was back in the House 2 weeks later, an East Sydney by-election having reinforced his position with his party and his constituents.

The East Sydney voters did not object to this additional democratic exercise, returning Reid again only 3 months later, at the federal election on 16 December 1903. His performance throughout the first parliament – like his policy statement ‘The fiscal problem: my fight for reform’ for the federal election – reveals Reid as above all a liberal democrat and a ‘parliament man’ rather than a party disciple.

While the Free Trade Party held their position at the 1903 election, the Protectionists, led by Deakin (after Barton’s elevation to the High Court in September) suffered losses picked up by Labor. The result was the short-lived Deakin government, defeated 6 weeks after the opening of the second parliament on 2 March 1904.

Reid saw what Deakin called the ‘three elevens’ parliament (each of the 3 parties holding an almost equal proportion of the seats) as an opportunity for a liberal alliance. Despite the fiscal differences, Reid anticipated the shaping of national parties on liberal and labour lines. Deakin might have shared this prediction, but like Barton, he was rigidly opposed to Reid.

When a vote on the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill demonstrated that Deakin did not have the necessary majority in the House of Representatives, he was required to advise the Governor-General on whether an alternative government could be formed. Once more Reid awaited the Governor-General’s call in vain. Deakin recommended that Lord Northcote ask Chris Watson to form a government.

The result was the installation of Australia’s first Labor government on 27 April 1904. Although Deakin and Watson had a mutual respect and liking, the alliance was both unlikely and unstable. The new Labor government shared Deakin’s recognition of Reid’s potency as a parliamentarian and of his ability, given the opportunity, to put in place a program that was not only effectively free trade, but effectively anti-socialist.

Facing a very brief period on the government benches, the Labor government made their priority the 2 bills they did not want a possible Reid government to inherit. They were all but successful with the first, the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. The second, the Seat of Government Bill 1904, confirmed the first 3 prime ministers’ wariness of the Leader of the Opposition.

‘The crow with the piece of cheese’

There was an important pre-Federation prelude to the Seat of Government Bill. When he had become Premier of New South Wales 10 years before, Reid had inherited from his predecessor, George Dibbs, the vigorous and at times bitter competition between New South Wales and Victoria over the siting of the national capital. Reid’s successor as Premier, William Lyne, was equally committed to Sydney becoming the nation’s capital.

The issue had been a hot topic at the 1891 and 1897–98 Federation conventions. When the Constitution Bill failed at the 1898 New South Wales referendum, the siting of the capital became a bargaining point. At the ‘secret’ premiers’ conference early in 1899, a compromise was reached. The site would be in New South Wales, but more than 100 miles (161km) from Sydney, and parliament would meet in Melbourne in the interim. Lyne immediately set up a royal commission under his friend, lawyer and outdoors man Alexander Oliver, to investigate suitable locations outside a 100-mile arc around Sydney.

As Melbourne’s Argus newspaper observed, New South Wales had been in the advantageous position of the fabled crow, the site of the capital the piece of cheese in its beak. The provision for the site was recorded in the Australian Constitution enacted on 9 July 1900, requiring the parliament to put the compromise decision into effect.

Oliver’s report (recommending Bombala) and the portfolio of Home Affairs made Lyne the ‘crow’ once the fight over the site began within New South Wales. Several locations within his southern electorate were named, including Tumut. By the end of the Commonwealth’s first year, there was a whole flock of crows – federal capital leagues were set up to advance the cause of other locations. Bathurst was favoured by Reid as the closest to the 100-mile limit.

In March 1902, 5 country regions were examined by a trainload of senators, and in May an entourage of members of the lower House set out to examine potential sites. Reid dismissed these as ‘Lyne’s picnics’ – unnecessary jaunts that he and other Sydney parliamentarians ignored. Lyne set up a federal royal commission which investigated nine sites. Albury and Tumut were ranked first in their August 1903 report. This recommendation meant that the Member for Eden-Monaro, Austin Chapman, joined Lyne and Reid in the contest. A fourth man, Labor’s King O’Malley, also entered the debate.

As Leader of the Opposition when the Seat of Government Bill was introduced by the Deakin government in October 1903, Reid was faced with a vote by the House for a site of 1000 square miles (1609 square km) at Tumut. This large slice of New South Wales not only raised the spectre of a socialist land nationalisation scheme, but was closer to Melbourne than Sydney. Reid’s hand in the ensuing debate can be seen in the loading of the Bill with additional specifications, for elevation above sea level, and a frontage to the Murrumbidgee as well as the Murray River. Even before this clumsy accretion went to the Senate, the Melbourne Age had joined the Sydney Morning Herald in declaring it ludicrous. The Senate amended the Bill, and it lapsed in the House of Representatives when parliament rose for the election.

The Deakin government, returned at the election, was out of office soon after parliament resumed on 2 March 1904. As a member of the Labor Caucus, King O’Malley was a key figure in pushing for a fast resolution on the national capital site. A new and brief Seat of Government Bill was drafted. Sent to the Senate first, the Bombala region was selected, with the provision that the federal capital territory ‘shall be an area of 900 square miles’ (1448 square km).

Reid was Leader of the Opposition when the Bill came to the vote in the lower House on 9 August 1904 and the site was amended to Austin Chapman’s choice of Dalgety. Reid had the provision for the area amended to a recommendation rather than a statutory provision. This second Seat of Government Bill was passed by both Houses on 15 August 1904, just 3 days before the Watson government lost its majority in the vote on the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill.

While William Hughes attacked Deakin for his failure to support the Labor government at the critical moment, Watson requested the Governor-General to dissolve the House of Representatives. Lord Northcote rejected this in favour of seeking a new ministry and sent for Reid. At last, he was to have his turn at the prime ministership.

Sources

- Crisp, LF, George Houstoun Reid: Federation Father, Federal Failure?, Australian National University, Canberra, 1979.

- Deakin, Alfred (edited by JA La Nauze), Federated Australia: Selections from Letters to the Morning Post, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1968.

- McMinn, WG, George Reid, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1989.

- Oldfield, Audrey, Women's Suffrage in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1992.

- Reid, George, My Reminiscences, Cassell, Melbourne, 1917.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 6 April 1891