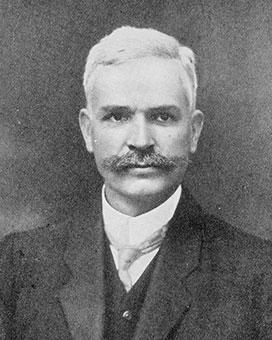

George Reid was Prime Minister from 18 August 1904 until 5 July 1905. His term was only 11 months, but it was the second longest of the first 7 federal governments. His Cabinet was a strong one that included experienced Protectionist ministers, but not their leader, Alfred Deakin.

Parliament sat for less than half of these 11 months, with a recess from December 1904 until June 1905. The contribution of the government Reid formed, with Protectionist Allan McLean as his deputy, was a handful of minor acts and, finally, the passage of the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904.

Cabinet

Reid’s Cabinet was ‘as much a geographical coalition as an inter-party one’. Around the Cabinet table sat a South Australian Free Trader (Josiah Symon as Attorney-General), three Victorian Protectionists (Allan McLean as deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Trade and Customs, George Turner continuing as Treasurer and James McCay as Minister for Defence). Then there were the 3 New South Wales Free Traders (Sydney Smith as Postmaster-General, Dugald Thomson as Minister for Home Affairs and Reid as Prime Minister and Minister for External Affairs). A Queensland Protectionist, James Drake, was Vice-President of the Executive Council.

Deakin had helped negotiate the ‘fiscal truce’ Reid had sought to form his ministry, and the program of the new government was one he and Reid had earlier discussed. But Deakin remained ominously aloof from Reid’s new ministry. He and his former Minister for Home Affairs, John Forrest, sat on the cross benches while Chris Watson led a Labor Opposition for the first time. A further complication was the decision by Isaac Isaacs, William Lyne and Littleton Groom to vote with the Opposition, creating not 3 but 4 different alignments in the House.

Reid turned his full attention to the parliament and was there for every one of the 57 sitting days in 1904. This was a necessity, as his majority was often borderline in both Houses. His government succeeded with the passage of the act setting up the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Court, and his Minister for Home Affairs, Dugald Thomson, engaged with New South Wales Premier Joseph Carruthers over the transfer of land for the federal territory.

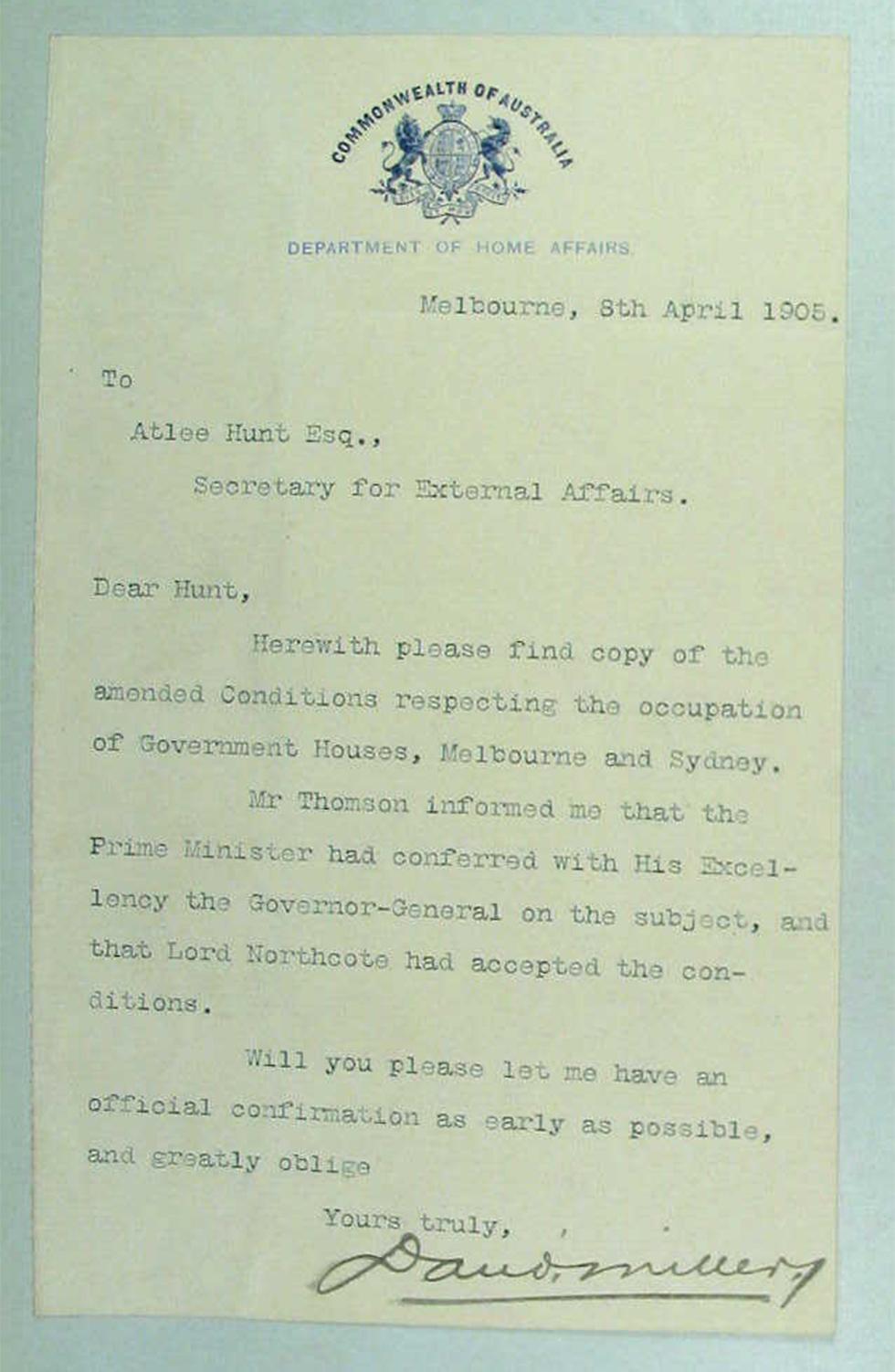

The business of establishing the government of a new nation involved issues small and large for each of the founding prime ministers. Reid, for instance, was called on to work out the matter of accommodation for the Governor-General in both Sydney and Melbourne once the interim arrangements for Lord Hopetoun and Lord Tennyson had lapsed. Just as the Victorian parliament had made way for the Commonwealth to occupy their Parliament House, so the Victorian Government House on St Kilda Road was made available for the Governor-General. Reid and the third Governor-General, Lord Northcote, set out what both regarded as an historic agreement on 24 March 1905. The arrangements for the occupancy of Sydney’s Macquarie Street Government House and the Melbourne Government House were a tacit recognition of twin temporary seats of Commonwealth government.

A letter confirming agreement between the Prime Minister and the Governor-General on the occupancy of the Government Houses in Sydney and Melbourne, 1905. NAA: A1, 1905/2828, p.11

Of the other preoccupations of the Prime Minister, one in particular reveals the passion of ‘Drydog’ Reid for imperial loyalty – his role in the establishment of Empire Day in Australia. Queen Victoria’s birthday on 24 May had been a long-established day of celebration in Britain and the Empire. After her death, a proposal to continue the observance was adopted in the other dominions and in many British colonies in 1903, though not in Britain until 1916.

Though some state governments had raised the idea, no Prime Minister had taken it up until Reid advanced a plan at the premiers’ conference early in 1905. The first Commonwealth observance of the day was 24 May 1905, 6 weeks before Reid lost the prime ministership, but for more than 50 years Australians celebrated Empire Day, until the late 1950s.

The High Court strike

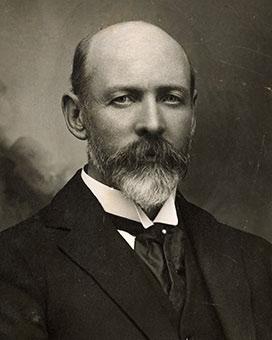

As well as challenges in the parliament, Reid’s term was marked by an extraordinary conflict in the High Court. The issue was ignited and inflamed by Attorney-General Josiah Symon and the Chief Justice of the High Court, Samuel Griffith, who was backed by the other members of the Court, Edmund Barton and Richard O'Connor.

Josiah Symon, a South Australian Senator and ‘possibly one of the best haters in Australia’ was Reid’s Attorney-General. A hard-working federationist, he had been personally affronted by an amendment the British parliament made to the Australian Constitution in 1900. This amendment enabled appeals from Australian courts to the Privy Council in London. Symon blamed the change on Samuel Griffith, who had been appointed in 1903 as Chief Justice of the High Court.

For the Court’s first year, Griffith made the 2-day train journey from Brisbane to Melbourne for sittings, with Barton and O’Connor making a 1-day rail trip from Sydney. In November 1904, Griffith moved to Sydney and requested that shelving for his law library be installed in the Darlinghurst Court House, where the Court frequently sat.

Instead of requesting his department to install the shelving, Symon charged the Court with ignoring the provisions of the Act passed by parliament in 1903 by deciding to sit outside Melbourne. In what amounted to a 6-month vendetta, Symon queried the judges’ travel expenses, delayed their reimbursement and refused the request for bookshelves.

This extraordinary situation developed not only because of the irascibility of the Chief Justice and the Attorney-General, but because the Prime Minister did not rein in his minister. Reid was aware of the conflict – and Symon’s capacity for escalating it – and took time off on his summer fishing holiday at Sorrento to write to Symon. Reid offered the rationalisation that the Court should not be centralised in Melbourne, where the parliament ‘was separately provided for’ and that, until the national capital was established in New South Wales, Sydney was the ‘true seat of government’. This unusual interpretation of the 1903 Act did nothing to quell the rising drama.

In April, Griffith announced the postponement of the Melbourne sitting scheduled for the following month until all the matters of travel expenses had been sorted out. Industrial action by the Court was an extraordinary notion, but even this did not end the matter. Instead, it died with the fall of Reid’s government on 5 July 1905. Within weeks of taking office as Attorney-General in the second Deakin government, Isaac Isaacs had addressed the problems, but the voluminous record of Symon’s campaign remains.

‘Without a whine’

While this tale unfolded during the long parliamentary recess in 1905, Chris Watson lobbied Deakin with a promise of Labor support to hold the line on protection. Deakin laid down this protection alliance challenge to Reid 4 days before parliament resumed, in a speech in his Ballaarat electorate.

In response, Reid withdrew the speech the Governor-General would give at the opening of parliament, outlining the government's program. Instead, before the parliament on Wednesday, 28 June 1905, Lord Northcote had to read the 6 sentences in which Reid returned Deakin’s serve by proffering an electoral redistribution.

All that remained was for Deakin and Watson that night to decide on the strategy to bring about a vote in the House. This was effected on the Friday. The following Wednesday, Reid was at Government House, where Lord Northcote again refused a dissolution, and sent for Deakin to form a government.

David Syme's Melbourne Punch wrote of Reid's ‘shrewd and bold challenge’ in using the Governor-General's formal speech to counter Deakin, and hailed Reid’s own speech ‘a masterpiece’. Londoners read Arthur Jose’s report in The Times that the Australian Prime Minister had ‘fallen on his sword’. Perhaps the greatest balm for Reid would have been the Punch observation that he ‘went out promptly and without a whine’.

Sources

- Australasian, 10 September 1904

- Crisp, LF, George Houstoun Reid: Federation Father, Federal Failure?, Australian National University, Canberra, 1979.

- French, Maurice, ‘One People, One Destiny – a question of loyalty: the origins of Empire Day in New South Wales 1900–1905’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 61, 1975, pp. 236–48

- McMinn, WG, ‘The High Court imbroglio and the fall of the Reid–McLean government’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol. 64, June 1978

- McMinn, WG, George Reid, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1989.

- Pegrum, Roger, The Bush Capital: How Australia Chose Canberra as its Federal City, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1983.

- Punch (Melbourne), 6 July 1905

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Governor-General’s Office – Inauguration of Empire Day, 1905, NAA: A6662, 470

- Agreement between Prime Minister and Governor-General re Government Houses, 1905, NAA: A1, 1905/2828

- Commonwealth Ministry, ministerial oaths, 1904, NAA: A5447, 7