Edward Gough Whitlam’s early years were spent in Melbourne, Sydney and then Canberra, where he finished school – several times. His law studies at the University of Sydney and newly married life with Margaret (nee Dovey) were interrupted by war, when he served in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) from 1942 to 1945.

Whitlam joined the Australian Labor Party in 1945. In 1952, aged 36, he became Member of the House of Representatives for the seat of Werriwa in Sydney. When Werriwa was divided in 1955, the Whitlams and their young children moved from Cronulla to Cabramatta.

In 1960, Whitlam was elected Deputy Leader and in 1967, Leader of the parliamentary Labor Party. He visited Vietnam in 1966, and the People’s Republic of China in 1971.

In 1972, 20 years after he had entered parliament, he became Prime Minister.

Growing up 1916–40

Whitlam was born in the Melbourne suburb of Kew on 11 July 1916. He was the elder of 2 children of Martha (Maddocks) and Frederick Whitlam. When the government of Andrew Fisher set up the Federal Land Tax Office in 1911, Frederick Whitlam joined the Commonwealth Public Service and worked at the tax office. In 1913, he was promoted to work in the office of the Crown Solicitor in the Attorney-General’s Department, headed by Robert Garran. William Morris Hughes was the Attorney-General in the Fisher government.

In 1921, Frederick Whitlam became Deputy Crown Solicitor for the Commonwealth. The family moved to Sydney, where they lived in the north shore suburbs of Mosman and then Turramurra. Whitlam went to school at Mowbray House and then Knox Grammar School.

Whitlam was 10 years old when, in 1926, his father was transferred to the new federal capital of Canberra. In 1927, he went to Telopea Park Intermediate High School, where he edited the school magazine, the Telopea. He completed the leaving certificate in 1931. Aged only 15, he was considered too young to go to university. He went to Canberra Grammar School to further his grounding in the classics by studying Ancient Greek. Whitlam sat the leaving certificate exam 3 more times between 1932 and 1934, and edited the school magazine, The Canberran.

The Whitlam family lived in a large house in the Canberra suburb of Forrest, next door to the family of Health Department head, JHL (John Howard Lidgett) Cumpston. In 1936, Frederick Whitlam became Commonwealth Crown Solicitor in the Attorney-General’s Department, when Robert Menzies was Attorney-General in the government of Joseph Lyons.

Whitlam enrolled at the University of Sydney in 1935. He completed an arts degree and began a law degree. His sport was rowing, and he was heavily involved in debating and the St Paul’s College Revues. He edited his college journal, The Pauline, from 1938 to 1941 and the student magazine, Hermes, from 1939 to 1941. His first appearance as prime minister was in 1940, when he played the British leader Neville Chamberlain in the St Paul’s College Revue.

At war 1941–45

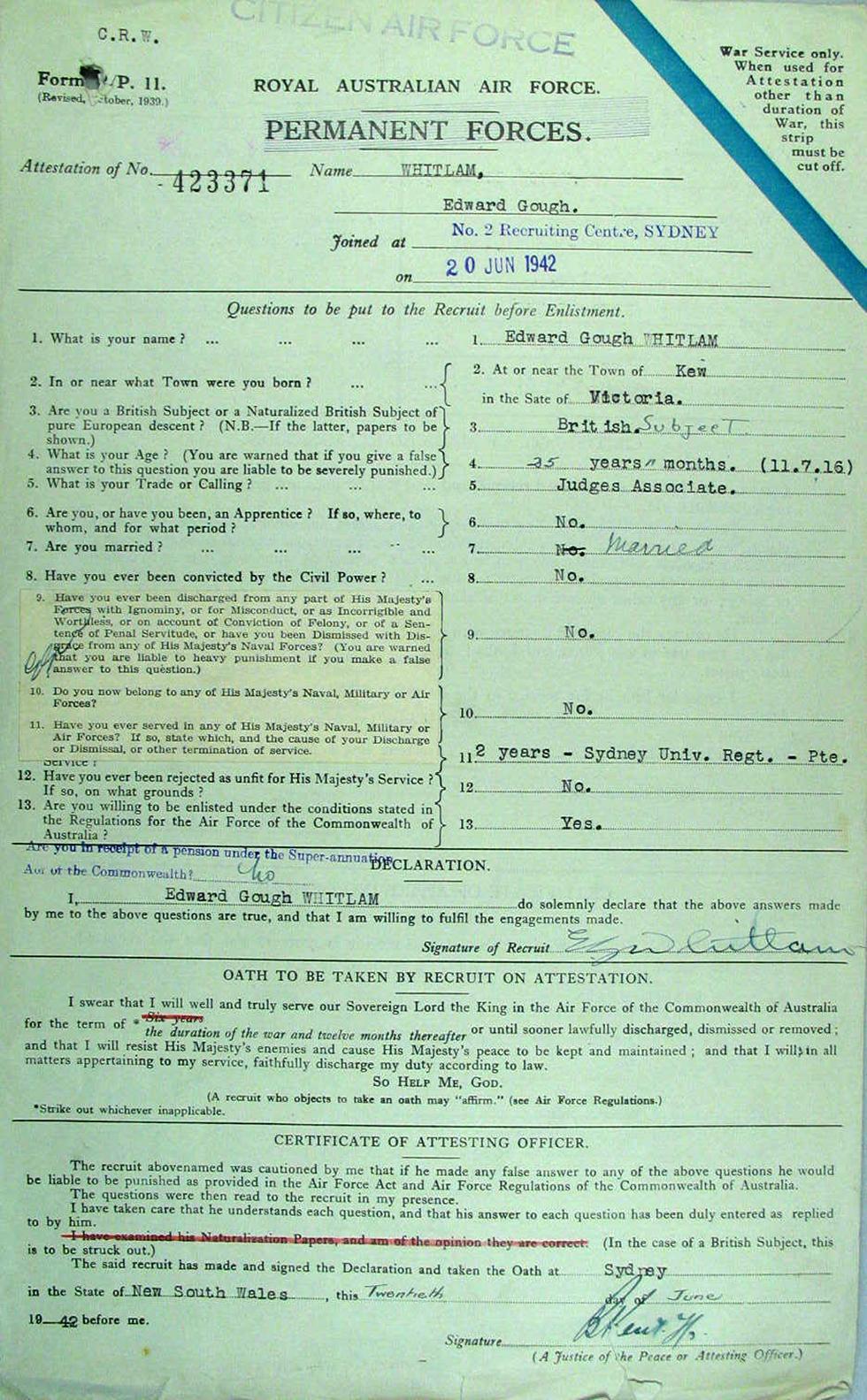

On 8 December 1941, the day Japanese aeroplanes attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, Whitlam registered with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). He was not called up until June 1942, 6 weeks after he and Margaret Dovey were married in Sydney on 22 April. Whitlam served as a navigator and was stationed for much of the war at Gove, on the eastern Arnhem Land coast of the Northern Territory. His squadron protected convoys off northern Australia, and later moved further north to undertake bombing raids on enemy supply camps in the islands and the Philippines. By the end of the war, Whitlam was navigator on the only Empire aircraft assigned to the RAAF Pacific Echelon at General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters at Leyte and Manila, flying members of MacArthur’s staff between the Philippines and Australia.

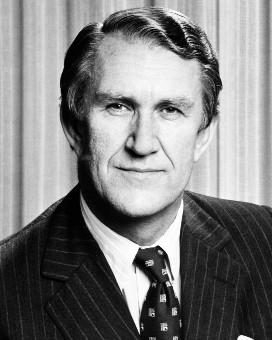

Photograph of Gough Whitlam from his RAAF officer personnel file. NAA: A9300, Whitlam E G, p.11

Gough Whitlam’s attestation paper from his RAAF officer personnel file. NAA: A9300, Whitlam E G, p.20

Whitlam’s sons, Antony and Nicholas, were born during his period of service in 1944 and 1945, respectively.

In 1943, when Whitlam was on leave in Sydney, he and Margaret Whitlam went to a Labor Party election meeting addressed by one of Prime Minister John Curtin’s ministers, Eddie Ward, and Minister for Information, Arthur Calwell. Back at Gove, Whitlam handed out Labor material to his squadron. The Curtin government was returned and the following year began campaigning for a referendum to give the Commonwealth wider post-war reconstruction powers. Again, Whitlam campaigned for the Labor government, firmly supporting the cause of expanding Commonwealth power. The referendum on 19 August 1944 was unsuccessful, although the vote from those serving in the defence forces was overwhelmingly in favour. Whitlam joined the Darlinghurst branch of the Labor Party on 8 August 1945, shortly after the death of John Curtin, while on his final period of leave from the RAAF.

Whitlam ended his service with the rank of Flight Lieutenant Navigator on 17 October 1945. He resumed his studies and completed his law degree at the University of Sydney, and was admitted to the New South Wales and federal courts as a barrister in 1947.

By 1947, the Whitlams had 2 small sons and, with the help of a war service housing loan, built a house in Wangi Street, Cronulla – a beachside suburb in Sydney’s south. Whitlam stood for the local government election for the Sutherland Shire Council in 1948, and for the Sutherland seat in the New South Wales parliament in 1950. The family did not own a car, and most of Whitlam’s campaigning was door-to-door along unfinished streets in the rapidly growing southern suburbs. He was not elected to either seat, but the campaigns made him a well-known local figure.

Whitlam was energetically involved in everything – the suburban progress association, his children’s school parents and friends association, and the Returned Servicemen’s League. He also became a radio celebrity, winning successive rounds of the Australian National Quiz Championship in 1948 and 1949, and was runner-up in 1950. The quiz was arranged to promote popular interest in the Chifley government’s security loans for post-war reconstruction. Broadcast live by the ABC, the quiz was avidly followed by many, including Prime Minister Ben Chifley. The prizes for championship winners were security bonds. Whitlam’s winnings totalled £1000, and the family used the money to buy the block of land next to their house.

Poster advertising the Australian National Quiz Championship of 1948. Gough Whitlam won this quiz in 1948 and 1949, and was runner-up in 1950. NAA: C934, 50

Whitlam was noticed by the Labor Party for his work during the New South Wales Liquor Royal Commission in 1951–52. Very different from the traditional Labor candidate with a trade union background, Whitlam had to overcome the disadvantage of perceptions that he was a ‘silvertail’ – someone whose privileged background would prevent him from representing typical Labor constituents. His capable performance during the Royal Commission, particularly when he stood in for his father-in-law, Justice Wilfred Dovey, was as useful as his consistent involvement in local affairs.

Member for Werriwa 1952

Whitlam stood for the federal seat of Werriwa at a by-election in November 1952, after the retirement of HP Lazzarini. Werriwa (or Weereewaa) is the Aboriginal name for Lake George. In 1901, the electorate centred on the rural city of Goulburn but 50 years later, it covered the rapidly growing south-east and south-west Sydney suburbs and extended to Wollongong. Whitlam won the seat with a record majority of 66% of the vote, and celebrated by buying the family’s first car and a hat – then essential to the politician’s outfit.

On 17 February 1953, Whitlam became a member of Australia’s 20th parliament. His first speech was scheduled for 19 March, but by then he had already spoken 3 times. He first rose on the motion of condolence on the death of his school friend Brian Green, son of the Clerk of the Parliament Frank Green. In Question Time, he had addressed questions to Minister for Labour and National Service Harold Holt and Minister for Commerce and Agriculture John McEwen. It was parliamentary convention for a maiden speech to be heard in silence, but Whitlam’s incisive criticisms had McEwen interjecting and earning the Speaker’s reprimand.

Whitlam was among the parliament’s most articulate members. In 1953, he attacked French policies in Indo-China, arguing for self-determination for the Vietminh. Just before Prime Minister Robert Menzies called the election in May 1954, the defection of Soviet Embassy officials Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov brought espionage activities and the threat of Communism to the front pages. In parliament on 12 August, Whitlam argued for the recognition of China and its admission to the United Nations. This was in line with the position taken by both Labor Party policy and Ben Chifley, but with the Cold War intensifying, it was a radical stance for an ambitious party member.

In 1955, the Labor Party split, the dissident anti-Communist faction later becoming the Democratic Labor Party. Whitlam was among those considered left wing and an ‘Evatt man’, but he also suffered a rumour campaign that he was at heart a Liberal whose Labor credentials were superficial. He retained his constituents’ support though, and was considered a ‘good bloke’ by those he represented.

Also in 1955, Whitlam’s electorate – the most populous in New South Wales – was divided. The south-eastern section was renamed Hughes after William Hughes, who had died in 1952 after 50 years in federal parliament. The western section, covering the Sydney suburbs of Liverpool, Cabramatta and Fairfield, retained the name Werriwa and became Whitlam’s new electorate.

The family, now with 4 young children, moved from their much-loved Cronulla house to make their home in Cabramatta, within Whitlam’s electorate. The Whitlams again began the hard work of getting to know people, and getting known, in the new neighbourhood.

The Menzies government set up a joint committee on constitutional review in 1956. Whitlam was one of the Labor Party members on the committee, which produced its first report in 1959. The experience on the joint committee demonstrated the possibilities, as well as the limitations, of constitutional reform and transformed Whitlam’s approach to Labor Party policy. He later described his membership of the committee as one of the great influences of his political life. Whitlam also served on the joint select committee on a new parliament house from 1965 to 1970, and on the House of Representatives Standing Orders Committee from 1960 to 1974.

Herald report on Communist plans to unite with the Australian Labor Party, taken from an ASIO file, May 1953. NAA: A6122, 447, p.38

Deputy party leader 1960–67

In 1959, Whitlam was elected to the Caucus executive, and was thus a member of HV (Bert) Evatt’s Shadow Cabinet. After Evatt resigned on 15 February 1960 to become Chief Justice of the New South Wales Supreme Court, Arthur Calwell was elected leader of the federal parliamentary Labor Party on 7 March. Whitlam won a tight ballot for the deputy leadership against Eddie Ward.

As Deputy Leader, Whitlam was able to hire staff and John Menadue, a young Treasury official, became his private secretary. Whitlam set about developing a more workable structure for a party looking forward to its next term of government, not back to its last more than a decade ago. At the election in December 1961, Labor lost by only 1 seat as the Menzies government held on to the seat of Moreton with the help of Communist Party voters’ second preferences. In August 1962, as Acting Leader of the Opposition during Calwell’s illness, Whitlam had another major clash with Deputy Prime Minister John McEwen. Describing the government’s responses to Britain’s move into the European Common Market as ‘shabby’, Whitlam said ‘a more global and less selfish attitude’ would have provided a better long-term outcome for Australia. That year, Whitlam was appointed Queen’s Counsel.

In March 1963, when the Labor Party’s decision-making body – the Federal Conference – met at Canberra’s Hotel Kingston, Whitlam and Arthur Calwell were involved in an inadvertent demonstration of the need for party reform. The 2 men walked over to the hotel late one evening to hear the decision reached by the 36 delegates regarding party policy on the government’s plan to allow the United States to build a communications base at North West Cape in Western Australia. The meeting had not finished and, as the party leaders were not members of the conference, they waited outside the hotel. Among the journalists also gathered there was Alan Reid, who quickly sent for a photographer and produced the telling image of the leaders of the party’s parliamentary wing waiting for the party’s organisational delegates – the ‘36 faceless men’ – to give them a policy.

When Robert Menzies called a snap election in November 1963, he made much of Labor’s difficulty in forming a policy on the US base and of the ‘36 faceless men’ caricature. After Labor lost ground in the election, Whitlam launched a stinging attack on his party’s ‘failure to devise modern, relevant and acceptable methods of formulating and publicising policy’ and demanded reforms to the machinery and processes. Moves to include the leaders of the federal parliamentary party on the federal executive were initiated, and a compromise arrangement was achieved at the party’s conference in Adelaide in 1967.

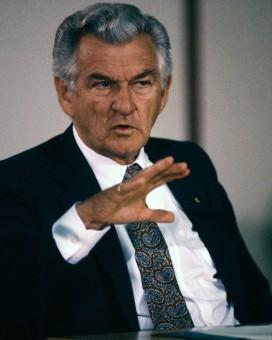

Gough Whitlam and Arthur Calwell in 1960, the year they took over as Leader and Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party. NAA: M155, B2

In January 1966, Robert Menzies retired and Harold Holt succeeded him as Prime Minister. The main issue at the federal election in November 1966 was the war in Vietnam, with demonstrations against Australia’s involvement plaguing the Coalition campaign. The month before the election, Whitlam visited Vietnam and toured the 1st Australian Task Force area in Phuoc Tuy Province.

Gough Whitlam with Lieutenant White and Major Rowe in Hoa Long village, Vietnam, August 1966. NAA: M155, B8

Leader of the Opposition 1967–72

Arthur Calwell retired on 8 February 1967 after the Labor Party’s poor result in the 1966 election. In April, Whitlam was elected party leader, with Lance Barnard winning the position of Deputy Leader. Whitlam was now in the right place to complete the reforms he had begun. His grasp of policy and the need for reform had developed over a decade. He referred to his long-planned changes to the party machinery, and modernising of the platform, as ‘the Program’. John Menadue coined the mantra ‘party, policy, people’ – ‘This year the party; next year the policy; 1969 the people.’

Gough Whitlam as Leader of the Opposition with his deputy, Lance Barnard, at Parliament House, 1969. NAA: A1200, L83519

Whitlam was the initiator and driving force behind this systematic revision of Labor policy, directed towards his grand vision of a post-Menzies era. His commitment led to major battles within the party. With Labor’s first full-time national secretary, Cyril Wyndham, Whitlam devised reforms targeting both the structure and policy-making processes of the party. Key goals included representation of the parliamentary party leadership on the federal executive, direct representation for ordinary members and reducing the power of paid officials. Despite the opposition of Victoria’s party executive and die-hard party traditionalists, major changes were effected.

Leader of the Opposition, Gough Whitlam, with British parliamentarian, Elwyn Jones, and South Australian Premier, Don Dunstan, 1968. NAA: A1200, L56423

In the overhaul of policies to create a new and topical platform, the emphasis was on urban development, international relations, housing and education. But foreign affairs – the independence of Papua New Guinea, and relations with China, Vietnam and Indonesia – health, defence and an end to the White Australia Policy were also included. In 1968, the Opposition forced through the Senate the appointment of a select committee on health costs. The government’s partial measures in response to the Nimmo Report, and doctors’ opposition to its recommendations, made Labor’s Alternative National Health Program attractive to electors.

Original transcript of Gough Whitlam’s speech for the Higgins by-election given at the Malvern Town Hall, February 1968. NAA: M170, 68/5, p.1

John Gorton became Prime Minister in January 1968, after the disappearance of Harold Holt in December 1967. Whitlam toured Vietnam again that year, and in 1969 went to Papua New Guinea.

In the 1969 federal election, Whitlam brought the Labor Party within 4 seats of victory, gaining 17 seats for Labor.

In 1971, when William McMahon had replaced Gorton, Whitlam led a Labor Party delegation to China. This was before the United States announced the proposed visit of US President Richard Nixon, and while the McMahon government was still refusing to open diplomatic relations with China.

Campaigning for the 1972 election with an ‘It’s time’ slogan, Whitlam declared:

Men and women of Australia! The decision we will make for our country on the second of December is a choice between the past and the future, between the habits of the past and the demands and opportunities of the future.

At the election on 2 December, enough voters responded to this declaration to elect a Labor government, with Whitlam as Prime Minister.

Gough Whitlam delivering a Labor Party policy speech, Blacktown, 1972. NAA: A6180, 5/12/72/5

Sources

- Freudenberg, Graham, A Certain Grandeur: Gough Whitlam in Politics, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1977.

- Hocking, Jenny, Gough Whitlam: A Moment in History, Melbourne University Publishing, Carlton, 2008.

- Oakes, Laurie, Whitlam PM: A Biography, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1973.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament: A Narrative History of the Senate and House of Representatives, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

- Walter, James, The Leader: A Political Biography of Gough Whitlam, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1980.