Edward Gough Whitlam was Prime Minister from 1972 to 1975, the first Labor Prime Minister since 1949. Labor’s reform plan, dubbed ‘the Program’, was immediately put into action by the first ‘duumvirate’ – a ‘ministry of two’.

The government fostered Australian participation in international agreements and became an active player in international organisations. Through ensuring Australia was party to international agreements, the Whitlam government initiated Australia’s first federal legislation on human rights, the environment and heritage. Gough and Margaret Whitlam travelled more widely than any of their predecessors.

The Whitlam government introduced reforms in every field. Some, such as health, housing, education and regional development, had been the preserve of the states but now became part of federal policy-making. The government became involved at every tier of education, including a needs-based aid for public schools program. The government established a Schools Commission and a national employment and training scheme, and abolished university tuition fees.

Implementing ‘the Program’ made parliament a busy place. A record number of Bills were introduced and enacted. By Whitlam’s own estimate, more than half his reform plan was implemented. But the Senate also rejected 93 Bills and triggered the events that led to the dismissal of the Whitlam government on 11 November 1975.

Original Michael Atchison drawing of Gough Whitlam, c.1972. Reproduced courtesy of Michael Atchison and The Advertiser. NAA: M151, 206

The duumvirate – ministry of two

On 5 December 1972, Whitlam became the first Labor Prime Minister since 1949. He and Deputy Prime Minister Lance Barnard were sworn into all portfolios, Whitlam holding 13 and Barnard 14. It was a mini-ministry that was unique in Australian political history. The duumvirate made 40 significant decisions in its brief tenure, including the immediate release of all draft resisters, the removal of troops from Vietnam and the recognition of Communist China.

Although it was a 2-man ministry, it was actually a 3-man government. To ensure there was no breach of propriety all decisions were made by the Federal Executive Council which has a quorum of three, including the Governor-General or their representative. Sir Paul Hasluck as Governor-General attended all meetings of the Federal Executive Council and participated in all decision-making and was thus effectively the third member of the first Whitlam government.

Caucus elected the full Ministry on 18 December and the 27 ministers were sworn in the next day. A wide restructuring revealed some of the new government’s program. There were new departments for Aboriginal Affairs (Gordon Bryant), Education (Kim E Beazley), Environment and Conservation (Moss Cass), Media (Doug McClelland), Minerals and Energy (Rex Connor), Northern Development (Rex Patterson), Social Security (Bill Hayden), and Urban and Regional Development (Tom Uren). Frank Crean was sworn in as Treasurer and Lionel Murphy as Attorney-General. Barnard was Minister for Defence, and Whitlam held the Foreign Affairs portfolio.

The first year 1973

On 15 December 1972, Whitlam and Barnard responded to the failure of the Northern Territory Gove Land Rights Case in 1971 by setting in train a Royal Commission into Aboriginal land rights under Justice Woodward. The findings of the Royal Commission would lead to the drafting of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 and the establishment of an elected National Aboriginal Consultative Committee. In 1972, the government also established the Department of Aboriginal Affairs in response to the 1967 referendum constitutional change that gave the Australian Government responsibility to make laws for Aboriginal people.

Prime ministerial press statement announcing the decision to hold an inquiry into Aboriginal land rights headed by Justice Woodward, 15 December 1972. NAA: M533, 2, p.57

In January 1973, Australia re-opened its embassy in Peking, resuming diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China after 24 years. Gough and Margaret Whitlam set out on a visit to Indonesia in September 1973 and travelled through South-East Asia. On 31 October Whitlam became the first Prime Minister to visit the People’s Republic of China.

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam with Premier Zhou Enlai in China, 1973. NAA: A6135, K15/11/73/20

As well as setting up new government departments in 1973, the Whitlam government amalgamated the various defence departments into a single agency.

On 25 July 1973, the Australian Legal Aid Office was established, with offices in each state capital.

Legislation was passed in August 1973 to establish the National Film and Television School in Sydney. In November, the Prime Minister unveiled a plaque launching the construction of a national gallery in Canberra. The government purchased Blue Poles by US artist Jackson Pollock for the gallery at a cost of $1.3 million. This was the highest price ever paid for a modern painting.

On 19 October, Queen Elizabeth II became Queen of Australia when she signed her assent to the Royal Style and Titles Act 1973. The Act deleted the traditional reference to her role as Head of the Church of England by removing ‘Defender of the Faith’ from her Australian titles.

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and Margaret Whitlam with Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip at The Lodge, 19 October 1973. NAA: A8746, KN30/10/73/62

In December 1973, the government established the Australian Development Assistance Agency to manage overseas aid programs, and the Schools Commission to implement a needs-based program of financial aid to government schools. The government also passed a Bill lowering the voting age to 18.

The second year 1974

The reform program for regional development produced results through direct grants to local government bodies around Australia. Grant programs included flood mitigation, urban renewal, leisure and tourist facilities, and building sewerage systems in unserviced urban areas. Under the Department of Urban and Regional Development, the Albury–Wodonga Development Corporation was established on 21 May 1974. It was intended to be a model for similar schemes elsewhere.

Gough Whitlam, Rupert Hamer, Robert Askin and Tom Uren arriving in Albury to sign the Albury–Wodonga Agreement, 1973. NAA: A6180, 24/10/73/77

Regional funding programs provided direct funding for community health centres and regional-based hospitals. By specifying the purpose of financial grants to the states, the government financed a national highway system and a standard-gauge railway line linking Perth, Adelaide, Sydney and Alice Springs. Brisbane’s city railway system was extended and electrified.

The Opposition majority in the Senate was a major obstacle to government Bills. The Senate’s rejection of 6 Bills provided the trigger for a double dissolution election in May 1974, when 18-year-olds voted for the first time. Labor was returned with 49.3% of the vote and a reduced majority in the House of Representatives. Although its Senate vote increased by 5%, the government was still without a majority in that House. On 5 August, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory were each granted 2 Senate seats.

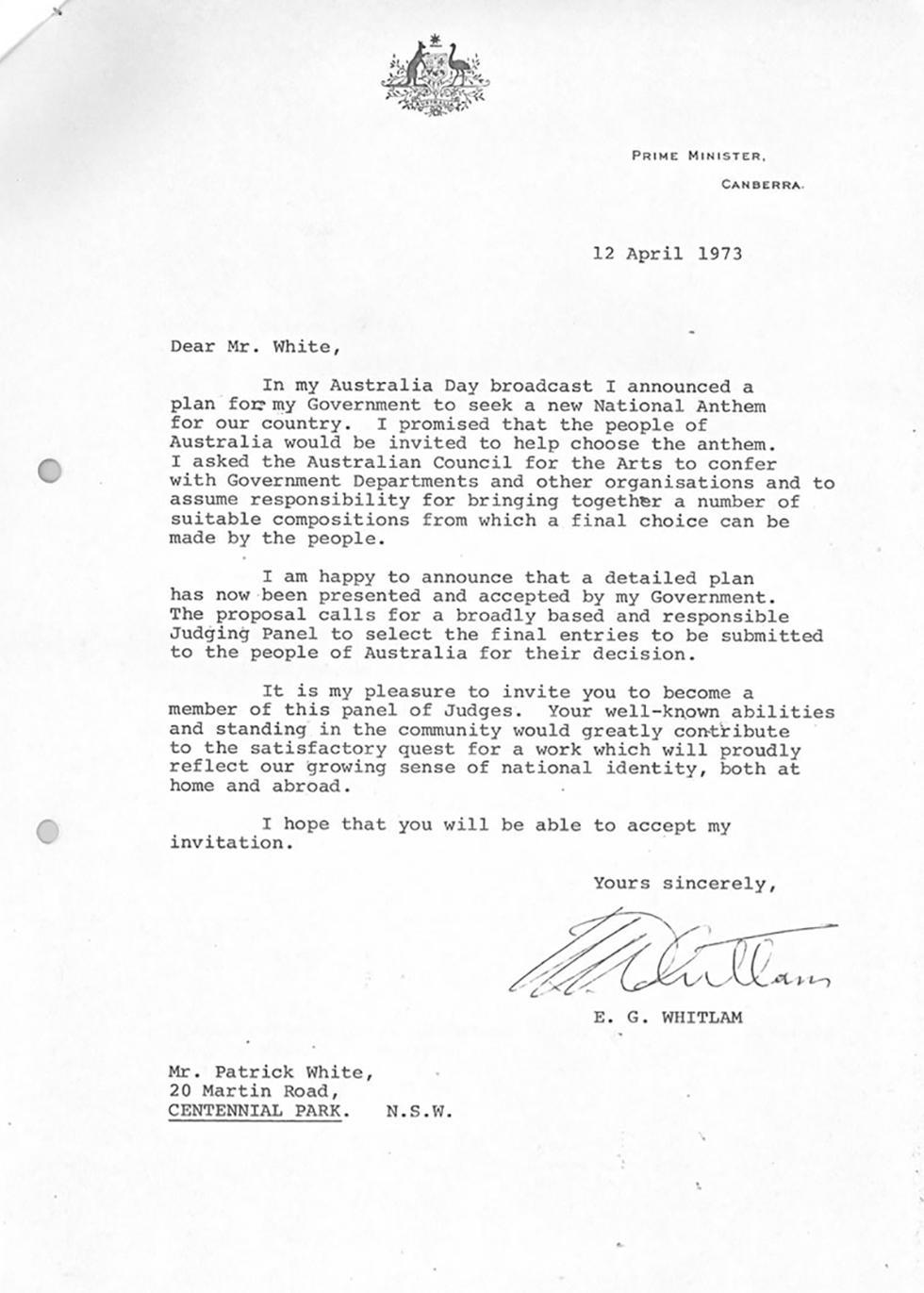

After national polling, on 8 April 1974 ‘Advance Australia Fair’ replaced ‘God Save the Queen’ as Australia’s national anthem. In June, the government appointed a national advisory committee for the United Nations’ proposed International Women’s Year in 1975. Margaret Whitlam chaired the committee and Elizabeth Reid, the Prime Minister’s adviser on women, headed the committee’s secretariat.

Letters from Gough Whitlam to Patrick White, Kath Walker, Manning Clark and David Williamson asking them to help choose the new national anthem, April 1973. NAA: M501, 3

Two Royal Commissions were announced in August 1974: one into human relationships and the other into intelligence and security. The Trade Practices Commission was established on 1 October, and the Australian Law Reform Commission was formally established on 1 January 1975.

The Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service was established in 1974 as part of the Department of Environment and Conservation.

After Cyclone Tracy destroyed much of Darwin on Christmas Eve 1974, Whitlam returned from a trip to Europe and inspected the devastation – hear the Prime Minister’s message to the cyclone victims.

Gough Whitlam with journalists at a press conference in the wake of Cyclone Tracy, Darwin, 1974. NAA: A6180, 31/12/74/65

The last year 1975

The Whitlam government continued its rapid pace of change. An Order of Australia replacing the British honours system was announced on Australia Day (26 January) 1975. In March, the Australian Film Commission and the Australia Council were established, and in April, a Consumer Affairs Commission commenced operation. In July, the Australian Heritage Commission was established.

In May, when a Technical and Further Education Commission was set up, the Whitlam government was able to introduce reforms at every tier of education, including a national employment and training scheme and the abolition of university tuition fees.

Attorney-General Senator Lionel Murphy was appointed to the High Court of Australia in February 1975. Keppel Enderby, Member for the Australian Capital Territory, replaced him as Attorney-General.

In June, the Family Law Act 1975 was enacted, creating the first no fault divorce procedure in the world and providing for a national Family Court (established in 1976). In June, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 also became law, ratifying a United Nations convention that, although signed by Australia, had remained unratified for 9 years. At the United Nations, Australia gave support to non-racial voting at the General Assembly, changing Australia’s voting on South Africa. Australia also banned South African sporting teams while that country remained under an apartheid regime.

Al Grassby, the first Commissioner for Community Relations, with Gough Whitlam at the proclamation of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. NAA: A6180, 4/11/75/23

Whitlam’s overseas travel in 1975 included a visit to Indonesia in April for meetings with President Suharto.

Gough Whitlam and President Suharto lunching al fresco with Australian and Indonesian officials, Indonesia, April 1975. NAA: A6180, 11/4/75/105

One of the most sweeping of the Whitlam government’s domestic reforms during 1975 was the establishment of Medibank, enabled by the Health Insurance Act 1973, which was passed at the 1974 joint sitting of parliament. The national health care scheme began operating on 1 July 1975 and incorporated many of the recommendations of the 1968 Nimmo Report. Comprehensive changes were also made in social welfare areas – a supporting mother’s benefit and a welfare payment for homeless people were introduced.

On 1 July 1975, 2 new communications agencies – Telecom and Australia Post – replaced one of the first departments established at Federation, the Postmaster-General’s Department.

Three major inquiries were appointed in 1975: a Royal Commission on Norfolk Island in May, an environmental inquiry into Fraser Island, and the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry in July.

On 16 August 1975, the Prime Minister formally handed the Gurindji people at Wattie Creek in the Northern Territory title deeds to part of their traditional lands. This was the culmination of a decade of struggle since the Gurindji first walked off Wave Hill Station to claim their traditional lands at Daguragu. A month later, Papua New Guinea celebrated independence from Australian administration.

Lowering the Australian flag for the last time at Papua New Guinea Independence Day ceremonies, 15 September 1975. Gough and Margaret Whitlam were among the dignitaries who attended the celebrations. NAA: A6180, 22/9/75/20

Implementing ‘the Program’ made parliament a busy place in the three years of the Whitlam government. A record number of Bills were introduced and enacted. By Whitlam’s own estimate, more than half his reform plan was implemented. But during these 3 years, the Senate rejected 93 Bills. This was more than the total number rejected during the previous 71 years of parliament, some 68 Bills.

Rivalry among ministers, including Whitlam and his Attorney-General, Lionel Murphy, exacerbated the government’s difficulties. Crisis came in the Loans Affair. In 1974–75, the government considered by-passing the Loans Council to raise US$4 billion in foreign loans. Although the plan was abandoned, Minister Rex Connor continued secret negotiations through an international broker, and Treasurer Jim Cairns misled parliament over the affair. Although Whitlam sacked both ministers, the Loans Affair enabled new Liberal Party leader Malcolm Fraser to justify refusing to vote on the budget Bills in the Senate. The aim was to force the government to an election while its electoral fortunes were in decline.

The New South Wales and Queensland premiers further reduced government numbers in the Senate when they broke with convention and made non-Labor appointments to 2 seats vacated by Labor senators. Cleaver Bunton replaced New South Wales Senator Murphy, who resigned on 10 February 1975 to become a Justice of the High Court. Then, when Queensland Labor Senator Bert Milliner died in June 1975, the government of Joh Bjelke-Petersen nominated Albert Field to the vacancy.

The dismissal

Whitlam decided against calling another double dissolution, and from October to November 1975 the parliament was in its worst political deadlock. The Opposition used its majority in the Senate to defer passage of the Budget, and the government was without a Supply vote to continue operating.

On 11 November, Governor-General Sir John Kerr broke the deadlock in an unprecedented move. When Whitlam visited Kerr to call for a half-Senate election, the Governor-General withdrew his commission as Prime Minister and replaced him with Malcolm Fraser as caretaker Prime Minister until an election could be held. The Senate passed the Budget on the same day. On 12 November, the Opposition, with a minority in the House of Representatives, replaced the government.

Gough Whitlam on the steps of Parliament House as the proclamation dissolving both houses of parliament is read, 11 November 1975. NAA: A6180, 13/11/75/33

The ‘dismissal’ sparked fierce public debate. Whitlam contended that the 1975 Budget had been stalled, not rejected, and, as some Liberal senators later confirmed, they would have soon voted to end the Senate deadlock. He argued that the crisis was political not constitutional, that it could have been resolved by political means and, if not for Sir John Kerr’s action, it would have been resolved in his government’s favour.

But a month later, the Fraser government was returned in its own right at the double dissolution election.

Sources

- Freudenberg, Graham, A Certain Grandeur: Gough Whitlam in Politics, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1977.

- Hocking, Jenny, Gough Whitlam: A Moment in History, Melbourne University Publishing, Carlton, 2008.

- Hocking, Jenny, ‘History by numbers’, introduction to Sybil Nolan (ed.), The Dismissal: Where were You on November 11, 1975?, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2005, pp. 1–14.

- Lloyd, Clem, ‘Edward Gough Whitlam’, in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland, Sydney, 2000.

- Lloyd, Clem and Gordon Reid, Out of the Wilderness: The Return of Labor, Cassell Australia, Melbourne, 1974.

- Oakes, Laurie, Whitlam PM: A Biography, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1973.

- Reid, Alan, The Whitlam Venture, Hill of Content, Melbourne, 1976.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament: A Narrative History of the Senate and House of Representatives, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

- Walter, James, The Leader: A Political Biography of Gough Whitlam, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1980.