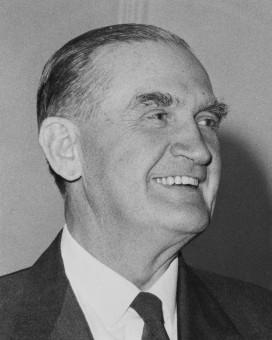

Before entering politics, John Grey Gorton served as a pilot in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) during the 1939–45 war. Twice forced to crash-land his aeroplane, first at Singapore and then in New Guinea, he also survived the sinking of his rescue ship when it was torpedoed.

Gorton won a Victorian Senate seat in 1949 and held it until 1968. He was a minister in the governments of Robert Menzies, Harold Holt and John McEwen. During the long prime ministership of Robert Menzies, Gorton held the portfolios of the Navy (1958–63), CSIRO (1962–63), Interior (1963–64) and Works (1963–66). In the Holt and then McEwen governments, he was Minister for Works (1966–67) and Minister for Education and Science (1966–68).

John Gorton’s Royal Australian Air Force enlistment papers, dated 8 November 1940, when he was 29 years old. NAA: A9300, GORTON J G, p.12

Growing up

Gorton was probably born on 9 September 1911, the second child of John Rose Gorton and Alice Sinn. No birth certificate has been located, but a Victorian birth registry lists a John Alga Gordon, born in Prahran on 9 September 1911. This record also wrongly gives his father’s name as ‘John Robert Gordon’. Also false was the belief that his older sister Ruth had died in infancy. In fact, she was living in South Africa, aged 93, when Gorton died on 19 May 2002.

To add to the uncertainty of these records, Gorton’s father told him some time before 1932 that his birthplace was actually Wellington, New Zealand. Gorton therefore gave his place of birth as Wellington when applying for a pilot’s licence in the United Kingdom, when he enrolled at Brasenose College, Oxford, and when he enlisted in the RAAF. The revised facts of his life, including that his parents never married, did not become public knowledge until he related them for a biography published in 1968 while he was Prime Minister.

Gorton’s early years were spent with his mother’s parents in Port Melbourne, as his parents made frequent business trips to Sydney, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. They finally settled in Sydney in 1916, where 5-year-old John was enrolled at Edgecliff Preparatory School. In 1920, his mother died of tuberculosis and his father took John to live with his wife, Kathleen, and John’s 12-year-old sister Ruth. John had known that he had a sister called Ruth, but had been told that she had died as an infant.

Kathleen Gorton and the two small children settled in Killara in Sydney. For the next 7 years, Kathleen Gorton looked after her husband’s son, while her husband lived in Melbourne and ran properties in northern Victoria. John Gorton attended Headfort College in Killara, and then boarded at Shore, the Sydney Church of England Grammar School. In 1927, Kathleen and Ruth moved to London. Gorton, aged 16, spent some time on his father’s orchard ‘Mystic Park’, Lake Kangaroo, near Kerang, in Victoria. He finished school as a boarder at Geelong Grammar, remembering these 2 years as the most productive and happiest of his school years. He was a prefect, and represented the school in rowing, football and athletics. Encouraged by the new headmaster, James Darling, Gorton visited the homes of the unemployed in Geelong. There he learnt a lesson he later took into politics – that society had a duty to care for those unable to control their own circumstances.

James Darling persuaded Gorton’s father to raise a mortgage and send his son to Oxford University. Gorton was admitted to Brasenose College in October 1932. He later claimed that he had ‘majored in rowing’, but he left Oxford in 1935 with a good upper second degree and a strong grounding in history, politics and economics. Visiting Spain in 1934, shortly before the outbreak of civil war, Gorton met 18-year-old Bettina Brown, an American language student at the Sorbonne in Paris. They married in 1935 and settled in Australia. Instead of pursuing his intended career in journalism, Gorton went to Lake Kangaroo with Bettina and took over his father’s orchard, ‘Mystic Park’.

War service 1940–45

After war broke out in 1939, Gorton joined the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Reserve. He formally enlisted in 1940. He trained at Essendon, Victoria, and Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, and then sailed for England where he completed training at Hendon. His squadron was to be sent to the Middle East, but the British government sent them instead to Singapore. The troopship arrived on 13 January 1942, 4 weeks before the Japanese army occupied the island. On the morning of 21 January, Gorton was forced to crash land his Hurricane on Bintan Island near Palembang, Sumatra. His harness was not fully tightened, and his face was seriously injured on the gunsight of the plane. Eventually rescued, he left Singapore on an ammunition ship that was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. He spent 24 hours on a crowded life raft before HMAS Ballarat rescued the survivors.

When he had recovered, Gorton joined No 77 Squadron and was posted to Darwin. Here, a mistake nearly cost him his life, but he executed an ‘extremely successful’ crash landing on a beach after inadvertently cutting the fuel supply. In February, the squadron was sent to Milne Bay in New Guinea to assist with the ‘mopping-up’ operations as US forces pushed the Japanese from the islands they had occupied for a year. At Milne Bay on 8 March 1943, Gorton had a third flying accident – he miraculously escaped when his Kittyhawk stalled and flipped over at take-off.

The following month, Gorton was posted back to Australia to the RAAF operational training unit at Mildura, Victoria. In 1944, Flight Lieutenant Gorton went to Heidelberg hospital for surgery, which could not fully repair his facial injuries. A conventionally handsome man, he had become an instantly recognisable one – an invaluable quality for a future politician.

After the war, Gorton returned to the orchard which Bettina Gorton had been running while raising their 3 young children, Johanna, Michael and Robin (born in 1937, 1938 and 1941 respectively). On 3 April 1946, at a welcome home for returned service men and women from the district, he made a speech that set out the credo of his future political career:

I believe that the returned serviceman wishes us to secure for all men that economic freedom which we have never had, and to which all who are willing to work are surely entitled. We must remove from the minds of men the fear of poverty as the result of illness, or accident, or old age. We must turn our schools into institutions which will produce young men and women avid for further education and increased knowledge. We must raise the material standard of living so that all children can grow up with sufficient space and light and proper nourishment; so that women may be freed from domestic drudgery; and so that those scientific inventions which are conducive to a more gracious life may be brought within the means of all. We must raise the spiritual standard of living so that we may get a spirit of service to the community and so that we may live together without hate, even though we differ on the best road to reach our objectives. And we must do all this without losing that political freedom which has cost us so dearly, and without which these tasks cannot be accomplished.

Encouraged to stand for the Kerang Shire Council, Gorton was returned unopposed in 1946 and remained on the council until 1952. He served as shire president in 1949–50.

Senator for Victoria 1949–68

A member of the Country Party, Gorton’s involvement in national politics began in 1947 when the Labor government of Ben Chifley decided to nationalise the private banks. Considering socialism to be the real enemy, Gorton supported moves in 1949 to unite the Liberal and Country parties. He was selected to stand for the new Liberal and Country Party (LCP) in the Victorian Legislative Council Northern Province. He lost to the well-known sitting Country Party member by just 300 votes in a poll of 15,000. Gorton was a member of the state executive of the LCP, and was placed third on the joint ticket with the Country Party for the 1949 Senate election.

The Liberal–Country Coalition led by Robert Menzies easily defeated the Chifley government in the enlarged House of Representatives. In the Senate though, the system of proportional representation had been introduced, and the Coalition did not fare as well. Gorton was a successful candidate, however, and was sworn in as a Senator for Victoria on 22 February 1950.

Gorton soon established a reputation as a ‘Cold War warrior’ and tough anti-Communist who, in his own party room, was apt to ask awkward questions of Menzies’ ministers. His major interests were defence and foreign policy, and he became the chairman of the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs. He spoke often of the need for Australians to have their own foreign policy (and their own nuclear weapons). He firmly advocated resisting totalitarianism in all its forms so there would be no repeat of World War II. On domestic matters, he defended or promoted what he saw as Victoria’s interests against those of other states. But he was equally concerned to advance the Commonwealth’s role in national affairs.

Minister for the Navy 1958–63

In 1958, Gorton was involved in a lawsuit over family share transactions that threatened his political career, but that October, the case was decided in his favour. The following month, Gorton retained his Senate seat at the 22 November federal election. After 9 years on the back bench, Menzies promoted Gorton to the Cabinet. Gorton proved to be an outstanding Minister for the Navy – he stopped the Navy’s postwar decline, modernised the fleet, prepared it for an expanded role in regional security, and improved the effectiveness of naval administration. His debating talents also helped him become a commanding figure on the Senate front bench, where he was spokesman for ministers in the House of Representatives. Gorton piloted the Menzies’ government’s Matrimonial Causes Bill through the Senate in 1959. Had this law applied 50 years earlier, it would have allowed his mother and father to marry.

Minister for Works 1963–67 and Education 1963–68

After the 1963 election, Robert Menzies moved Gorton to the Works portfolio. More importantly, he made him ‘Minister assisting the Prime Minister in Commonwealth activities relating to research and education which fall within the Prime Minister’s Department’. Gorton retained this position when Harold Holt replaced Menzies in January 1966. After the federal election in November 1966, Holt appointed Gorton the Minister for Education and Science.

In his 5 years as Education Minister, Gorton presided over the major foray of the Commonwealth into education areas which had been the business of the states. Controversially, Gorton promoted state aid to non-government schools. Less contentious measures included the creation of colleges of advanced education, the provision of more funds for academic and technical scholarships, more funds for the universities, and improved salaries for staff in tertiary education.

The new Department of Education and Science outlined, with the announcement of John Gorton as the first minister. NAA: AA1969/212, 36, p.36

Gorton was a hardworking and ‘hands on’ minister who consulted ‘down the line’, made up his own mind, was always forceful and did not respect protocol. Sitting in Holt’s Cabinet, however, he rarely paid attention to matters outside his immediate concern. As he did not hold a major domestic portfolio, he was hardly known outside his own area or even in Parliament House, outside the Senate wing.

Then, in October 1967, Gorton came to public prominence in the so-called ‘VIP affair’. The Labor Opposition had mounted a damaging challenge to the government over the use of the VIP government planes. When requested in the House, Holt failed to reveal the names of passengers who flew on VIP flights. This was seen as a denial that the information could be obtained. Repeated stonewalling and obfuscation by senior public servants, and the failure of Peter Howson, the Minister for Air, to resolve the matter, caused the Holt government growing embarrassment as the 1967 Senate election approached. Recently promoted to leader of the government in the Senate, Gorton discovered the information did exist, and obtained and tabled in the Senate the passenger manifests from the Department of Air. Overnight, he had saved the government.

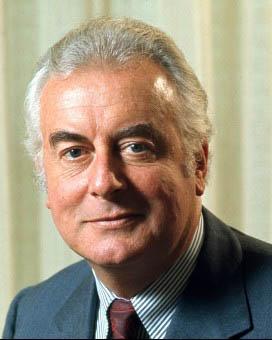

It was a crucial moment. Gorton’s new-found popularity among worried government backbenchers helped his bid for the party leadership after Holt disappeared off Cheviot Beach, Portsea, on 17 December 1967. Paul Hasluck, the Minister for External Affairs, emerged as Gorton’s greatest rival. John McEwen, leader of the Country Party, had been sworn in as caretaker Prime Minister until a new Liberal leader was elected. McEwen had ruled out further participation in the Coalition if William McMahon, the deputy Liberal leader, became Prime Minister. Leslie Bury, Minister for Labour and National Service, and Billy Snedden, Minister for Immigration, also nominated but were clearly outsiders.

Gorton won the ballot of 81 Liberal Party parliamentarians on 9 January 1968, probably by a small margin of 3 to 5 votes. He enjoyed strong support among the Senators, and some ministers and younger backbenchers in the House believed he would have the necessary popular appeal. Importantly, he seemed the best person to deal with Gough Whitlam, the Leader of the Opposition. As a senator, however, Gorton first had to resign and win a seat in the House of Representatives. This was achieved when he won Holt’s former seat of Higgins on 24 February 1968, and was sworn in to the House of Representatives on 1 March.

Sources

- Hancock, Ian, John Gorton: He Did It His Way, Hodder, Sydney, 2002.

- Trengove, Alan, John Grey Gorton: An Informal Biography, Cassell Australia, Melbourne, 1969.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Pilot Officer John Grey Gorton – Casualty file, Department of Air, 1942–43, NAA: A705, 163/34/154

- John McEwen and William McMahon rift, 1967–1968, NAA: M3787, 32