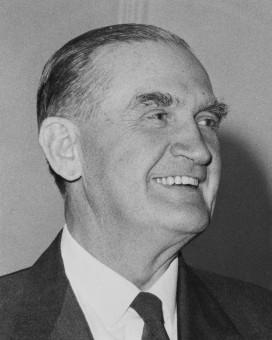

During John Grey Gorton’s term as Prime Minister (10 January 1968 – 10 March 1971), matters of defence were prominent. In domestic matters, the Australian Council for the Arts, the Australian Film Development Corporation and the National Film and Television Training School were established. Rates of pay were standardised between the sexes and Australia’s mining industry grew rapidly during this period. Gorton’s policy of economic centralisation caused friction with the States and inter-party crises threatened to destroy the Liberal–Country Party Coalition.

Delegates to the 1969 Five Power Defence Conference gathered in Kings Hall, Parliament House include (left to right): Prime Minister Holyoake of New Zealand, Minister for Defence Allen Fairhall, Prime Minister John Gorton, British Secretary of State for Defence Denis Healey and Tun Razak of Malaysia. NAA: A1200, L81806

The Cabinet and the ministry

Gorton retained the Holt-McEwen ministry he inherited until after he won the Higgins by-election on 24 February 1968. Even then, he did not make the expected drastic changes in membership. He dropped 2 junior ministers, Peter Howson and Don Chipp, from the outer ministry. 2 other vacancies had been created by Harold Holt’s death and Senator Norman Henty’s retirement. Gorton filled the 4 vacancies by promoting four backbenchers to the outer ministry. Malcolm Scott and Reginald Wright were promoted from the Senate, Phillip Lynch and William Wentworth from the House of Representatives. Gorton made just 2 changes to Cabinet. He promoted Malcolm Fraser from the outer ministry to take over his Education and Science portfolio, and Senator Ken Anderson to be Minister for Supply.

When Paul Hasluck retired from parliament in February 1969 to become Governor-General, Gorton elevated Gordon Freeth to Cabinet as Minister for External Affairs. He also promoted Dudley Erwin, the Chief Government Whip, to be Minister for Air. At the October 1969 election, Allen Fairhall (Minister for Defence) retired and Freeth lost his Western Australian seat.

From this point, Gorton’s ministry began a sequence of changes that continued for the remaining 15 months of his prime ministership. After the 1969 election, Senator Colin McKellar (Country Party) retired, and Malcolm Scott, Dudley Erwin and Charles Kelly were dropped from the ministry. Malcolm Fraser replaced Allen Fairhall as Minister for Defence and Peter Nixon became the fourth Country Party member of Cabinet. Don Chipp, Senator Robert Cotton, Senator Thomas Drake-Brockman (Country Party), Mac Holten (Country Party), Tom Hughes, James Killen and Andrew Peacock were promoted into the ministry. Minister for National Development David Fairbairn announced his refusal to serve in a Gorton Cabinet. Fairbairn and William McMahon, the Treasurer and Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party, unsuccessfully challenged Gorton for the party leadership. McMahon was subsequently moved from Treasury to External Affairs and Leslie Bury became Treasurer. Just before he lost office, Gorton brought Ralph Hunt into the ministry as the Country Party replacement for the retired John McEwen. Doug Anthony, the new Country Party leader, became the deputy Prime Minister.

Gorton took a close personal interest in some subjects, including defence and foreign policy, social welfare, Commonwealth–state relations, the environment and the arts. On the whole, however, he left ministers alone and was prepared to back their judgement. He seemed especially careful to support his Country Party ministers, particularly John McEwen, the deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Trade and Industry. At the same time, he was accused by David Fairbairn and others of making policy on the run, of acting in haste and of being a ‘one-man band’.

There were occasions when Gorton did act ahead of a Cabinet decision. Much to Fairbairn’s annoyance because he was by-passed, Gorton broke an impasse over the fixing of oil prices by negotiating directly with Australian drilling companies to secure a 5-year agreement which, it turned out, delivered lower petrol prices to Australian motorists. Cabinet subsequently endorsed the oil pricing agreement.

The ‘Gorton style’

Political commentators and his Coalition colleagues often referred to the ‘Gorton style’. They noted his friendly and relaxed manner, his approachability, irreverence, random brusqueness and perennial candour, his tendency to speak ‘off the cuff’, to be unorthodox and unpredictable (to those who did not know him), and his careless habits of dress, the cigarette always in his hand and the jaunty grin. Tony Eggleton, his press secretary, described him as a ‘Monday to Friday’ Prime Minister. His ministerial colleagues saw him as someone who could work much faster than Holt, who paid considerable attention to detail and readily comprehended the things that mattered.

Gorton did, however, believe that a Prime Minister should have a life outside his official duties, and could always find time for a swim, tennis, late night parties and conversations with friends. Rumours circulated about his behaviour – sometimes with an element of truth. Concerns about his personal behaviour eventually hurt him politically, particularly after a March 1969 incident involving a late-night visit to the American Embassy with a young woman journalist became public. Earlier in the day, the US Ambassador had invited Gorton to call after the dinner, and the journalist had asked him for a lift home. Although their convivial conversation with the Ambassador went on until 5am, and apparently included matters such as US policy in Vietnam, Gorton was unrepentant.

A mark of the Gorton style was his unwillingness to accept at face value the advice he received from senior public servants. His experience of the VIP affair, which was a factor in his decision to replace John Bunting as Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department, his instinctive distrust of Treasury and External Affairs, and his readiness to consult ‘down the line’, meant that Gorton alienated many public service mandarins. His choice of Lenox Hewitt to take over from Bunting gave him an able ally in his desire to cut through the bureaucratic process, but further harmed his relations with senior public servants. They, and some ministers, were appalled when Gorton replaced prime ministerial private secretary Peter Bailey with Dudley Erwin’s far less experienced staffer, Ainsley Gotto.

Commonwealth–state relations

Gorton believed that the Commonwealth government should assume greater responsibility for national affairs – a position closer to Labor than his own party. He thought the Liberal Party should bring party dogma into line with practice by abandoning its 1948 commitment to ‘the maintenance unimpaired of the federal system’. Gorton refused repeated requests by state Liberal or Coalition governments to allow the states to re-enter the income tax field. He insisted that state governments balance their budgets and stop begging the Commonwealth to meet shortfalls. In 1970, he was thwarted by threats on his own side to cross the floor when he sought to give the Commonwealth sovereignty over Australia’s territorial waters and continental shelf. All the states, including the Labor government of South Australia, objected to what they saw as a diminution of their sovereign rights and a threat to their access to off-shore mining royalties.

It was Gorton’s determined stand over Commonwealth–state relations which did him the most harm within the Liberal Party, especially as the federal Labor Opposition generally supported him.

Defence and foreign policy

During Gorton’s term as Prime Minister, defence was a compelling national issue. The Gorton government inherited Australia’s commitment to the war in South Vietnam and to the defence of Malaysia and Singapore from Communist insurgents. Gorton himself was ambivalent about what was then called ‘forward defence’. He opposed any increase in the size of the Australian contingent in South Vietnam above the 8000 already there. In his view, Australia would be better and less expensively served by building a mobile force based on Australian soil.

Prime Minister John Gorton with Indonesian President Suharto in Djakarta (now Jakarta) during Gorton’s visit in 1968. NAA: A1200, L73540

At the end of 1970, the Gorton government began the Australian withdrawal from South Vietnam when it did not replace the 8th Battalion when it ended its tour of duty. This was by no means a clear decision. With army chiefs hostile to any hint of withdrawal, Cabinet reached the decision reluctantly and against army advice. The army’s Cabinet submission in response was, in the view of one senior official, ‘argumentative, impudent and wilful’.

Gorton also rejected any open-ended commitment to Malaysia and Singapore. He advocated a physical presence in the region to ensure American and British support in the event of further Communist expansion or general instability. The ‘Five Power’ arrangement represented the growing interest of Australia and New Zealand in Malaysia and Singapore, and the receding interest of Britain. It was a delicate situation where Gorton had to balance his preference for an independent policy with the need to maintain a partnership with Australia’s traditional ‘great and powerful friends’. He did not achieve the desired balance, but he did establish a good working relationship with the administration of US President Richard Nixon, and with both a Labour and a Conservative government in Britain.

Nationalism

Gorton considered himself to be ‘Australian to the boot heels’, and wanted to make Australians proud of their country. He supported the Australian film and television industry, promoted the peaceful use of nuclear energy (using Australian uranium), and acted in September 1968 to prevent the foreign takeover of a major Australian company, the Mutual Life and Citizen’s Assurance Co Ltd (MLC). He helped establish the Australian Industry Development Corporation in 1970 to enable Australian companies to develop the country’s natural resources, and to prevent overseas control over those resources. This was a favourite project of Country Party leader John McEwen.

Prime Minister John Gorton at the tracking station at Honeysuckle Creek in the Australian Capital Territory during the Apollo II moon landing on 21 July 1969. NAA: A1200, L82037

Health, social welfare and education

Over 3 annual budgets, the Gorton government provided free health care for 250,000 poorer families, increased the allowances for the aged, invalids, widows, war pensioners and incapacitated ex-servicemen, liberalised the means test and made greater concessional allowances. His government provided more capital grants for educational institutions, scholarships for secondary and tertiary level students and aid to non-government primary schools. A key feature of the 1970–71 budget was the tapered reduction of personal income tax.

Aboriginal affairs

While Gorton strongly supported Commonwealth intervention in Aboriginal affairs in the area of education, health and housing, his government re-affirmed the orthodoxy of assimilation of Aboriginal people into the dominant culture. Gorton strongly opposed the notion of Aboriginal land rights on the ground that its implementation would promote separatism. He applied the same reasoning that lay behind his support for the existing immigration policy of restricting the entry of non-Europeans – that only those who could be fully assimilated should be accepted.

Prime Minister John Gorton with officials at Gove in 1968, during Gorton’s visit to the Yirrkala area in western Arnhem Land. NAA: A1200, L77441

Gorton visited the Northern Territory in 1968, and included on his itinerary Gove, on the Gulf of Carpentaria. This area was the subject of the Yolngu people’s petitions to the Parliament in 1963, when the Commonwealth leased areas for bauxite mining to Comalco without consultation. Gorton’s trip coincided with the start of the Gove land rights case, Millirrpum v Nabalco, in the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory – the first attempt at judicial recognition of traditional occupation in Australia.

Destruction and self-destruction

While Gorton had the capacity to attract and hold the affection of ‘ordinary Australians’, he built up a formidable list of enemies on his own side of politics. By March 1971, they included the Liberal state premiers, many Liberal state parliamentarians, leading members in the state party organisations, members of the Melbourne Club, discontented and ambitious federal backbenchers and a few members or former members of the ministry.

These groups objected to all or some of what they saw as Gorton’s attitudes towards the states, his assault on party principles, his alleged Labor sympathies, his defence and foreign policies, and his personal style and behaviour. Their hostility was further aroused by the severe reversals suffered by the government in the House of Representatives election of October 1969 (an anti-Coalition swing of 7%) and the half-Senate election of November 1970 (a 5% drop in the Coalition vote). In a 1972 interview, Gorton blamed the party’s conservatives who opposed ‘ideas in advance of their time’, like his emphasis on controlling overseas investment, or expanding Commonwealth powers in relation to the states. He also blamed the campaign team for having his policy speech recorded in a studio rather than delivered in public, thus making it ‘lifeless’. But others blamed Gorton himself for the election reversals in 1969 and 1970. By the beginning of 1971, anti-Gortonites in the party room were looking for an opportunity to remove him.

Malcolm Fraser, the Minister for Defence, provided the occasion. Stories circulating in the media from mid-February 1971 appeared to highlight a division between the Department of Defence and the army over the objectives and progress of civic action in South Vietnam. Gorton assured Lieutenant-General (Sir) Thomas Daly that he would support the Army. Questioned by journalist Alan Ramsey, Gorton refused to comment on whether Daly had complained to him about Fraser’s disloyalty to the Army and its minister Andrew Peacock. Fraser, in turn, complained that Gorton had been disloyal to a senior minister. He resigned on 8 March 1971, and accused Gorton in parliament the next day of not being ‘fit to hold the great office of Prime Minister’.

A party room meeting on 10 March proceeded to debate and vote on a motion of confidence in Gorton as leader. With the result a 33–33 tie, Gorton stated ‘that is not a vote of confidence’ and stepped down. In the election for a replacement, William McMahon, who had long been aiming at the prime ministership, was subsequently elected to succeed him. In a surprise move, Gorton nominated for, and was elected to, the deputy leadership.

2 views have emerged about the reasons for Gorton’s fall. One was that Gorton destroyed himself by being too much his own man. Another was that conservative Liberals brought him down because they were unable to accept necessary change, and were helped by a virulent press campaign against the Prime Minister. Throughout his life, Gorton had always ‘done it his way’, and he continued to do so. Without being sufficiently ‘political’, he pursued a self-destructive path within his own party.

Typically, Gorton shrugged off the defeat he had not anticipated. But he remained bitter about one aspect of it. In Gorton’s view, Malcolm Fraser, the presumed loyalist, had struck him without warning and this was something he would neither forgive nor forget.

The achievement

Gorton believed that ‘a good Prime Minister should have intelligence and integrity’, ‘a good constitution to keep going’, ‘stamina’ and ‘a deep love of this country’. Above all, a Prime Minister had to avoid the ‘tendency’, in circumstances where the hold on power was uncertain, ‘to avoid conflict, not to stir up anything, to govern in a low risk political environment’. Prime ministers should ‘recognise and grasp opportunities’, and be prepared to take a risk ‘regardless of the short term cost’.

Gorton certainly met his own criteria, with predictably mixed results. He took on battles against the Liberal grain, and against the states, such as his decision to legislate for Commonwealth control over sea borders. In areas of free health care for poorer families, a greatly expanded social service system, increased benefits and more Commonwealth money for education, the Prime Minister himself led the advance.

Gorton’s ‘my way’ approach produced a mix of gains and losses, for him personally and for his prime ministership. There were practical achievements, such as the establishment of the Australian Industry Development Commission and of a national Film and Television School. While it might have been Gorton’s ministers who pushed harder than their Prime Minister for environmental policies like the protection of the Great Barrier Reef, or in Aboriginal affairs for entitlement to land or the fulfilment of the new responsibilities gained in 1967, these remain achievements of his term as head of government.

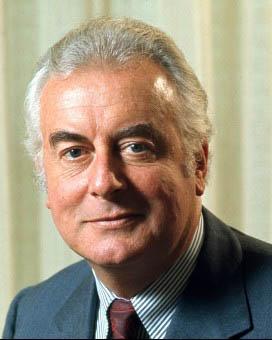

Other achievements, such as the difficult beginning of the end of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, were the result of external and electoral factors. In a top secret Cabinet submission, Defence Minister Malcolm Fraser warned of escalating public pressure for troop reduction once US President Richard Nixon’s decision to scale back US forces in Vietnam was announced. Similarly, the push towards eventual independence for Papua New Guinea should be seen in the light of Opposition pressure, given Gough Whitlam’s announcement of Labor’s goals for the Territory on his 1969 visit. But Gorton initiated key moves, such as the process of extricating Australia from overseas defence commitments, and obliging the states to accept that the Commonwealth would control financial relations and others areas of national interest.

Sources

- Hancock, Ian, John Gorton: He Did It His Way, Hodder, Sydney, 2002.

- Henderson, Gerard, ‘Sir John Grey Gorton’, in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland, Sydney, 2000.

- Hughes, Colin A, Mr Prime Minister: Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1976.

- Reid, Alan, The Gorton Experiment: The Fall of John Grey Gorton, Shakespeare Head Press, Sydney, 1971.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Visit of Prime Minister to Vietnam 1968, NAA: A1209, 1968/8176

- British Military presence in SE Asia discussions between PM Gorton and PM Wilson Secretary of State for Defence Mr Healey London, 1968–1969, NAA: A1209, 1969/7186

- David Fairbairn resignation from Gorton Ministry 1969, NAA: M3787, 48

- Malcolm Fraser resignation as Minister for Defence, press cuttings, 1971, NAA: A5954, 1201/34