On this page

Paul John Keating was Prime Minister from 20 December 1991 until 11 March 1996. He won office in a Labor Caucus ballot and lost it in a federal election.

Keating painted a ‘big picture’ of Australia’s future as a republic of equal citizens bound not by old ties to Britain, but by new alliances and attitudes that would create an economic, strategic and cultural future in its Asia-Pacific neighbourhood. He committed his government to securing economic improvement by expanding regional trade relations and reducing unemployment. His vision of Australia as a republic involved reconciliation through recognition of the land rights of Indigenous people, as well as the achievement of constitutional independence.

Keating achieved 2 of 3 key priorities. His government strengthened the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum and passed Australia’s first national native title legislation. A third priority – to provide employment to those excluded from the labour market – was less successful, and his economic goal of ‘efficiency with equity’ remained a vision rather than a reality.

Economic reform

Keating was sworn in as Prime Minister on 20 December 1991. There was an extensive reshuffle of portfolios, but few changes in personnel. John Dawkins replaced Ralph Willis as Treasurer and Graham Richardson moved from Social Security to Transport and Communications.

Keating hosted the visit of United States President George H Bush in January 1992, 3 weeks after taking office. This provided Keating with the opportunity for discussions to encourage greater US involvement in Pacific trade policies. He saw this as a key to the development of a strong trade region in the Asia-Pacific. The visit of George and Barbara Bush had been planned by former Prime Minister Bob Hawke following Australia’s role in the 1990–91 Gulf War. Hawke had also arranged the state visit of Queen Elizabeth II in February, which Keating also hosted. After these visits, Hawke resigned from parliament, on 20 February 1992.

In his first term, Keating focused on domestic economic problems. He launched his government with an announcement that he would attack unemployment and mend the damaged economy as a basis for implementing programs of economic and social equity. This priority he presented as closely linked to his ‘big picture’ of Australia’s future as a republic of equal citizens no longer bound by old ties to Britain. Instead, the nation would build a future in its Asia-Pacific neighbourhood. This close link between national and international policies characterised the new Prime Minister’s outlook and his time in office.

Keating became Prime Minister when Australia was in a prolonged economic recession, with 8 quarters of declining economic growth. At the end of February 1992, Keating released One Nation, an economic program for the creation of 800,000 jobs by 1996. With the unemployment rate continuing to climb throughout Keating’s first year as Prime Minister, the government’s responses included the Australian National Training Authority Act 1992, establishing an agency to coordinate training opportunities, increase workforce skills and provide for a youth training wage. The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 provided a uniform base for the elimination of employment discrimination against disabled people. The moves to reduce social security spending and turn this expenditure into a productive investment through job support, was used by both the Hawke and the Keating governments to address the escalation of welfare costs from the 1970s.

Prime Minister Paul Keating signs autographs for fans at Manuka Oval in Canberra, during the cricket match between the Prime Minister's XI and the West Indies in 1992. NAA: A6135, K19/11/92/24

Growth figures improved, suggesting the recession was lifting. But unemployment figures also rose, reaching 11.4% at the end of 1992 – the highest since the Depression in the 1930s. With an election due, Keating named 13 March as the date and campaigned on reducing the company tax rate and providing income tax cuts. Determined and effective campaigning against a ‘goods and services’ consumption tax proposed by Leader of the Opposition John Hewson, dominated the campaign launched at Bankstown Town Hall in Keating’s electorate. It was an election most political commentators expected Keating to lose. At the election night celebration at Bankstown Sports Club, he dubbed this the ‘sweetest victory of all’.

In a speech on 21 April 1993 to the Institute of Company Directors in Melbourne, Keating announced wide reforms in industrial relations. The government’s economic performance, or the tense economic times, or both, were leading to a deficit larger than the Hawke government had inherited from the Fraser–Anthony Coalition in 1983. Post-election, it was clear the more expensive promises could not be kept. Keating revised the pre-election tax cuts promise, proposing they be delivered in 2 stages. To achieve this, the government needed to reduce government expenditure on a range of programs. This meant a clash with the 2 parties holding the balance of power in the Senate, the Democrats and the Greens, when their priority programs were targeted.

In May 1994, Keating presented Working Nation to parliament, the government’s 5-year program for expanding employment, particularly for the young unemployed, by creating 2 million jobs. With reduced inflation and good growth in 1994, recovery from the recession seemed to be at hand. By the end of 1994, unemployment dropped to 9.3% and economic growth continued to improve.

Keating’s emphasis, as Treasurer and as Prime Minister, was on improving the competitiveness of Australian industry in a global market. The focus was on a general lowering of tariff levels within the Asia-Pacific region, and tying Australia to the economic strength of China, Japan and the United States. There was by no means universal support for these moves, not even within the government. Opposition within the Labor Party continued from those who saw increased protection as necessary for a stronger manufacturing sector and thus more jobs. When unemployment rose, Keating’s plan lost support both within the party and within the electorate.

International relations

Keating’s first overseas trip as Prime Minister was to Indonesia in April 1992. It was the first official visit there since Bob Hawke’s visit in 1983. Australia’s relationship with Indonesia had grown with the trade and investment opportunities fostered in these nine years. Under President Suharto’s ‘new order’, economic, diplomatic and cultural relations had grown, but Indonesia’s repression of the East Timorese independence movement and ongoing human rights abuses complicated cooperation. Despite the violent suppression of demonstrators in Dili in February 1992, Keating was as convinced as his predecessors that Australia’s geopolitical realities demanded a fostering of cooperation with Indonesia often at the expense of East Timor. At the April 1992 meeting with President Suharto, Keating secured support for his proposal to develop the role of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC), established in 1989 as an informal discussion group. Keating was a driving force in getting agreement to regular meetings of the heads of government of member countries – a key to building APEC into a body guiding the overall development of free trade and practical economic cooperation in the region.

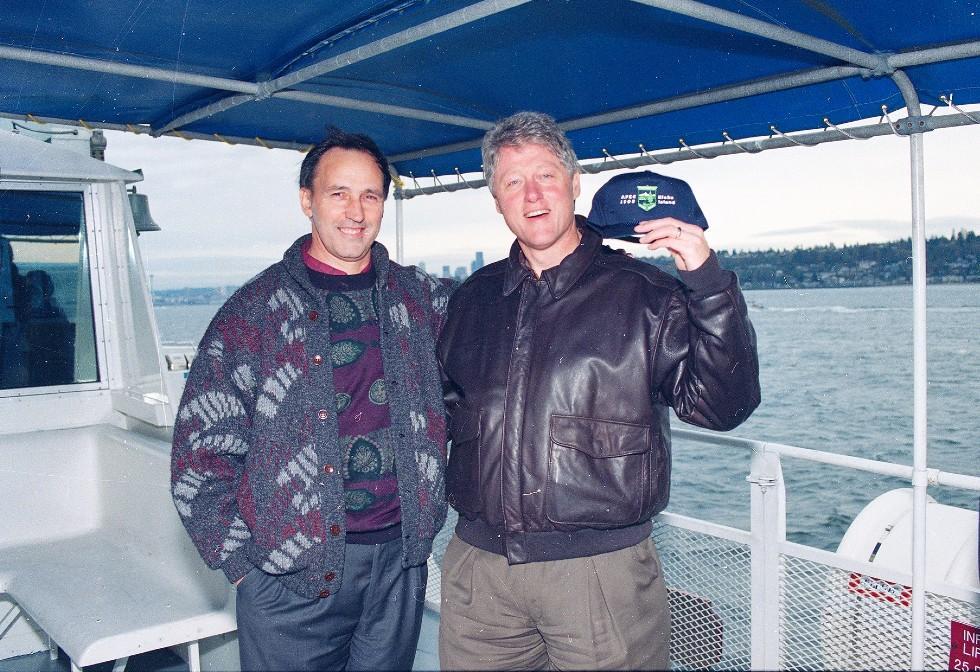

In September–October 1992, Keating had top-level meetings in Japan, Cambodia and Singapore. All had the issue of strengthening APEC on the agenda. The focus on such visits during his term in office is a measure of the importance Keating placed on a strong regional trade group for Australia’s economic stability. In 1993, he sent 2 of his closest advisers as ambassadors to Washington and Japan, and visited both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Korea to campaign for the APEC plans. After Bill Clinton became US president in November 1992, the door was open for US agreement to the plan and a year later President Clinton hosted the APEC meeting in Blake Island, Seattle. This meeting was a triumph for Keating’s APEC aims, although he had not been able to win Prime Minister of Malaysia Dr Mahathir to his cause and Malaysia was not represented at this key meeting.

Paul Keating with United States President Bill Clinton during the Prime Minister's trip to Seattle for the 1993 APEC conference. NAA: A8746, KN30/11/93/116

In 1994, Keating continued his regular meetings in APEC countries, visiting Laos, Thailand and Vietnam in April, and Indonesia in June. He saw these countries as strategically significant to Australia – a security buffer to the vast and powerful People’s Republic of China. He also visited Japan and the United States, the major trading nations of the region and vital to the success of a strong APEC presence in a world divided into economic regions. The Bogor treaty, finalised when APEC met in that Indonesian city in November 1994, was a peak achievement in this aim. The Bogor agreement linked APEC members in a proposal to achieve free trade by the year 2010 for industrialised countries, and by 2020 for all member countries.

On a visit to Japan in May 1995, Keating was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws by Tokyo’s Keio University for his work in the Asia-Pacific region. At the end of 1995, Keating launched the Australia–Malaysia Society at Parliament House in Canberra. In January 1996, he made the first official visit to Malaysia in a decade, healing the rift that had meant Prime Minister Mahathir did not attend APEC leaders’ meetings.

Of all the elements of Australia’s international relations between 1991 and 1995, the building of these Asia-Pacific relationships was the most significant. Other important areas included ratification of international instruments for environmental protection such as the Antarctic (Environmental Protection) Legislative Amendment Act 1992, which provided for Australia’s obligations in Antarctica under the Madrid Protocol. In 1995, there was a particular focus on Australia’s role in the South Pacific Forum, with Australia chairing the 15-member forum when France announced new nuclear testing in the Pacific. In an article published in Le Monde on 28 June 1995, Keating outlined the objections to any such move, saying that for the 15 countries in the region, ‘the Pacific Ocean is our Europe’.

In April 1993, Paul Keating appointed a Republic Advisory Committee to examine options for Australia’s development as a republic. This was part of a national ‘big picture’ – a shared commitment to shaping the nation as an independent republic, with progress towards social justice as its foundation. This involved not only constitutional change, but also furthering the movement for reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation was established by the Keating government in February 1992, under the Hawke government’s Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Act 1991. Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Robert Tickner presented the Commonwealth’s response to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody on 24 June 1992, outlining a program and expenditure to implement the recommendations of the Royal Commission’s report.

The High Court’s historic decision in the Mabo case in June 1992 raised the question of how to give legislative effect across Australia to this recognition of Indigenous title to land. Some 6 months after the decision, Paul Keating launched Australia’s program for the International Year for the World’s Indigenous People at Redfern Park in Sydney on 10 December 1992. He delivered a speech that announced the government’s intention to succeed ‘in the test which so far we have always failed’, and followed this speech with a year of negotiations to achieve the enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 and the Land Fund Act 1994. This provided the first national recognition of Indigenous occupation and title to land in Australian legislation. The Land Fund and Indigenous Land Corporation (ATSIC Amendment) Act 1995 amended the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989 to establish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Fund and Indigenous Land Corporation.

Keating saw economic development as the essential foundation for social development, and the achievements of his government were thus conditional on turning around the economic problems. By the time he called his second election for 2 March 1996, although unemployment was less than in 1993 and interest rates were lower than in 1990, foreign debt was mounting.

Although Keating had pursued his grand vision towards recognition of the rights of Indigenous people and towards an Australian republic after he won the 1993 election, his second term was marred with problems in his ministry, as well as the ongoing ‘fallout’ of the process of deregulating the economy. In his second term, Keating lost 4 senior Cabinet ministers. John Dawkins resigned as Treasurer in December 1993, then came the involuntary resignations in March 1994 of Graham Richardson and Ros Kelly. A public controversy continued to preoccupy Carmen Lawrence.

Labor was defeated and a Liberal–National Party coalition led by John Howard won office with a 40-seat majority in the House of Representatives.

Sources

- Blewett, Neal, A Cabinet Diary: A Personal Record of the First Keating Government, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 1999.

- Catley, Bob, Globalising Australian Capitalism, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1996.

- Day, David, ‘Paul John Keating’ in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland Publishers, Sydney, 2000.

- Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, Melbourne, 1996.

- Gordon, Michael, A True Believer: Paul Keating, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1996.

- Watson, Don, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: A Portrait of Paul Keating PM, Knopf, Sydney, 2002.