On this page

- Prime Minister 1939–41

- Coalition government

- Around the world 1941

- Opposition back bench 1941–43

- Leader of the Opposition 1943–49

- The Menzies era 1949–66

- Communism and espionage

- Parliament and public service

- Trade and international affairs

- The monarchy

- Defence

- Retirement

- Sources

- From the National Archives of Australia collection

Robert Gordon Menzies was in office twice, from 1939 to 1941 and from 1949 to 1966. Despite 7 successive federal election victories, Menzies’ second period as Prime Minister was not secure. In the 1954 and 1961 federal elections, the Labor Party received a greater proportion of first preference votes for House of Representatives seats (50.03% in 1954) than the Liberal and Country parties combined. Menzies was fortunate to come to office in a growing postwar economy. He also benefited from the Labor split in 1955, and skilfully exploited ‘Cold War’ fears and the threat of Communism for electoral gain.

Prime Minister 1939–41

Menzies was 44 years of age when he was sworn in as Prime Minister for the first time on 26 April 1939. He succeeded to the office following the death of Joseph Lyons and headed a minority United Australia Party government. Country Party leader Earle Page was Prime Minister after Lyons’ death, but he refused to serve in a government headed by Menzies, and had withdrawn his party from the coalition.

In his first ministry, Menzies held the Treasury portfolio. There were 9 ministers and four junior ministers: William Hughes (Attorney-General, and Industry), Richard Casey (Supply and Development), Geoffrey Street (Defence), Henry Gullett (External Affairs), Senator George McLeay (Commerce), Senator Hattil Foll (Interior), Eric Harrison (Postmaster-General, and Repatriation), John Lawson (Trade and Customs), Frederick Stewart (Health, and Social Services), James Fairbairn (Civil Aviation and Vice-President of the Executive Council). Ministers without portfolio were John Perkins (administering External Territories), Percy Spender (assisting the Treasurer), Senator Philip McBride (assisting in Commerce), Senator Herbert Collett (administering War Service Homes) and Harold Holt (assisting in Supply and Development).

In a radio broadcast made the night his ministry was sworn in, Menzies spoke of his humble upbringing and how he had made his own way in the world. He pledged his government, which he said ‘means business’, to look to the nation’s defence and ensure justice for all Australians.

The growing threat of war was the dominant political issue throughout 1939. Menzies strongly supported British appeasement policy on Nazi Germany – keep the door open for negotiation, but also prepare for war – and was as surprised as anyone else by the signing of the German–Soviet non-aggression pact. He was also concerned about Japanese intentions in the Pacific and took steps to establish Australian embassies in Tokyo and Washington so Canberra could receive independent advice about developments to Australia’s north.

On 1 September 1939, fears of imminent war were realised when Germany invaded Poland. Britain and France, who had guaranteed Polish sovereignty, issued an ultimatum to Germany that it withdraw its forces. Germany ignored the warning and on 3 September 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany.

Menzies broadcast to the nation that same evening, announcing his:

melancholy duty to inform you officially that, in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war on her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.

Later that week, parliament met and the leaders of the Labor and Country parties both pledged their support. Not a single member questioned the correctness of the assertion that Australia was part of Britain’s declaration of war. Nor did anyone query Menzies’ view that he could appeal for the nation’s support ‘because we are all Australians and British citizens’.

The government immediately put the nation on a war footing. A National Security Act, modelled on the War Precautions Act of 1914, was passed. The recruitment of a volunteer military force for service in Australia and abroad was announced, and almost immediately became known as the 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The citizen militia was called up for local defence. However, Menzies did not immediately offer Australian troops to Britain. He was uneasy about Japan’s intentions in the Pacific and, until that threat became clearer, he was cautious about committing Australian troops overseas. Britain’s ongoing failure to develop Singapore as an adequate Pacific defence added to his concern.

Menzies’ cautious approach was overtaken, however, when the New Zealand government offered troops to assist Britain and RG (Richard) Casey, who had been sent to London to discuss wartime cooperation, promised a matching Australian contribution. Without consulting Canberra, Britain dispatched scarce shipping to carry Australian troops to Egypt for training. Privately Menzies was furious with the British for their ‘quite perceptible disposition to treat Australia as a Colony’. Publicly he had no choice but to support a decision he privately disagreed with – to send Australian troops overseas.

From September 1939, the government’s attention focused on defence issues. A special War Cabinet was created, initially comprising the Prime Minister and 5 senior ministers (Richard Casey, Geoffrey Street, Senator McLeay, Henry Gullet and William Hughes). Even the 1941 Child Endowment Act was, in part, devised to ensure industrial peace while the nation was at war. Menzies also found himself with increased responsibilities. In December 1939, he added the new Department of Defence Co-ordination to his Treasury and prime ministerial duties. Then in February 1940, he took over an additional load when John Lawson was forced to resign the Trade and Customs portfolio over allegations regarding the sale of a racehorse.

Coalition government

To add to Menzies’ burdens, for a nearly a year he headed a minority United Australia Party government that depended for its survival on the support of the Country Party. At the beginning of the war, Earle Page had indicated the Country Party’s willingness to join a composite government. Menzies flatly refused such an alliance, if it meant having Page in the Cabinet. Although the Country Party elected a new leader, Archie Cameron, soon after, negotiations again broke down when Menzies insisted on being able to choose which Country Party members would be admitted to the Cabinet.

In March 1940, Cameron conceded Menzies’ right of veto and a new UAP–Country Party coalition government was formed with Country Party ministers Archie Cameron, Harold Thorby and John McEwen, and junior ministers Arthur Fadden and Horace Nock. The creation of a new ministry allowed Menzies to shed the Treasury and Trade and Customs portfolios.

With the end of the Nazi blitzkrieg on Poland, the period of the ‘phoney war’ meant community fear and apprehension gave way to complacency. To assuage panic at the beginning of the war, Menzies had spoken of ‘Business as Usual’. The phrase would come back to haunt him when, in the spring of 1940, the war took a dramatic turn for the worse. Germany successfully invaded Denmark and Norway, and then began its assault on Belgium, Holland and France. By the end of June 1940, France had fallen and Britain, supported by its dominions, stood alone against Nazi Germany.

Menzies responded to these developments by calling for an ‘all in’ war effort. With the support of John Curtin, leader of the Labor Party, the National Security Act was amended to provide the government with enhanced powers: unlimited power to tax, to acquire property, to control business and the labour force, and to conscript manpower for the defence of Australia. Menzies also made some key appointments to mobilise the nation’s resources, the most important of which was asking Essington Lewis, the head of Broken Hill Proprietary Ltd (BHP), to become Director-General of Munitions Supply.

A federal election was due to be held towards the end of 1940. In the run up to the election, Menzies and his government were dealt a blow when in August 1940 a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) plane crashed while trying to land at Canberra’s airfield. The Chief of the General Staff and 3 senior ministers, James Fairbairn, Henry Gullet and Geoffrey Street, were among those killed. All 3 ministers were close and loyal friends of Menzies.

A week after the tragedy, Menzies announced the federal election for 21 September 1940. His hopes for a decisive result – a resounding victory or defeat for the government – were dashed when the United Australia Party–Country Party coalition and the combined Labor parties won 36 seats each. Two Independents, Arthur Coles and Alex Wilson, who could be expected to support the coalition, held the balance of power.

Menzies sought to break the impasse by forming an all-party national government, but Labor leader John Curtin resisted. While fully supporting the war effort, Labor had its own objectives. Instead Curtin proposed an Advisory War Council, where the government could inform and consult with the Opposition on any matter to do with the conduct of the war. It was not what Menzies wanted, but he accepted the proposal as a way of achieving some degree of cooperation with the Opposition. Menzies was forced to make other compromises as well. When forming his new ministry, Menzies reluctantly appointed Earle Page Minister for Commerce. There were 2 other new Country Party ministers, Thomas Collins and Hubert Anthony, and one new United Australia Party minister, John Leckie. Country Party leader Arthur Fadden became Treasurer.

Around the world 1941

In late January 1941, Menzies flew to Britain to hold discussions about the weakness of Singapore’s defences. It was Menzies’ first overseas trip as Prime Minister (he had twice travelled overseas while Attorney-General) and the first time an Australian Prime Minister had journeyed overseas by aeroplane. The first stopovers for the Qantas Empire flying boat were at Singapore and Cairo. In Singapore, Menzies was not impressed with the defence preparations he saw, nor with the quality of the British commanders he met. In North Africa, he visited as many Australian servicemen as he could and toured the 6th Division battlefields at Bardia, Tobruk and Benghazi.

Menzies arrived in Britain on 20 February 1941. He met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and was invited to join the British War Cabinet for the duration of his stay. He was there when the proposal to use Australian soldiers in the ill-starred Greek campaign was first raised. He sought a proper military evaluation of the expedition’s chances, fought for promises of full equipment for the troops and insisted on consulting his Cabinet before making a commitment. He remained dubious about the campaign’s rationale and prospects of success, but eventually gave his support.

Menzies’ cautious approach clashed with Churchill’s brisk way of reaching a decision. Menzies further antagonised Churchill by secretly meeting with the President of Irish Free State, Eamon de Valera, in a well-intentioned but naïve attempt to end Irish neutrality in the war.

While in Britain, Menzies experienced first-hand the devastation caused by German air raids. He was deeply moved by what he saw and visited some provincial British cities and war factories to help boost morale. But Menzies was unable to achieve an increased commitment from Britain for Singapore's defence. With the blitz still in progress and the threat of German invasion not yet passed, Churchill promised only to keep Australia's concerns in mind.

In May 1941, Menzies flew back to Australia via Lisbon and the United States. He was accorded an enthusiastic public reception on arrival home. Within the coalition, however, rumblings about his leadership had grown louder during his absence. There was little direct questioning of Menzies’ ability. Rather, he was said to be unpopular in the electorate and (because of his perceived arrogance) unable to maintain coalition solidarity. He was also criticised for his inability to form an all-party national government. When news broke of the disastrous campaigns in Greece and Crete, his critics held him at least partly responsible.

In June, Menzies announced a complete reorganisation of government. Joseph Abbott, Allan McDonald and Eric Spooner joined the ministry when 5 new departments were created. Cabinet was increased to 26 ministers and 15 junior portfolios. The reforms were intended to make government structure more efficient and, by increasing Cabinet numbers, to shore up his position in the party. Menzies also announced the creation of 7 all-party committees to advise the government on matters ranging from manpower and resources to taxation and rural industry.

But Menzies could not deliver the national all-party government that a growing band of coalition and press critics desired. The deteriorating war situation – Germany had invaded the Soviet Union, while Japan’s aggression in Indo-China provoked new fears of war in the Pacific – only added to the government’s unease.

In August, Cabinet decided that Menzies should return to Britain to represent Australia’s interests in the British War Cabinet. With government and Opposition numbers in the House finely balanced, this required the approval of the Labor Party. Labor leader John Curtin considered the matter, but a majority of the Labor Caucus insisted that at a time of crisis it was the Prime Minister’s duty to remain in Australia and provide effective leadership at home.

Faced with the Labor Party’s veto and the constant criticism directed at him from within his own party, Menzies called an emergency Cabinet meeting. He told his colleagues the only feasible course was for him to resign and recommend to the Governor-General that John Curtin be asked to form a government. Cabinet members urged instead that Labor again be approached to form a national government, with equal ministerial representation from both sides of the house. Labor again rejected the offer. A majority of Cabinet then expressed the view that a new leader was needed, and on 29 August 1941 Menzies resigned as Prime Minister.

When Menzies stood down as Prime Minister on 29 August 1941, he also resigned as leader of the United Australia Party. William Hughes replaced him as party leader. The new Prime Minister, Arthur Fadden, asked Menzies to remain as Minister for Defence Co-operation.

The Fadden government lasted barely a month. On 3 October, Coles and Wilson, the two Independents holding the balance of power in the House of Representatives voted with Labor to defeat the coalition government. On 7 October, John Curtin became Prime Minister and Menzies became an Opposition backbencher.

Opposition back bench 1941–43

Showing remarkable resilience, Menzies did not resign from parliament. The sense of public duty that had drawn him into politics had not been extinguished, and in wartime it would have been difficult for Menzies to rebuild his legal practice.

In 1942, Menzies began a series of weekly Friday night radio broadcasts over station 2UE Sydney, which were relayed to stations in Victoria and Queensland. He used these short talks – the best known of which was ‘the forgotten people’ – to refine his political philosophy and present his vision for postwar Australia. 2 themes dominated the talks: that the concept of class war ignored the aspirations of most Australians and that education was the best means of achieving social and economic advancement for all.

The simple, arresting messages had the ring of sincerity because so much of their content was autobiographical. The humble middle-class home Menzies idealised was the home he had grown up in. And the child who received an assured future, not through inherited wealth, but through a sound education, was himself.

Menzies also gradually resumed his activities within United Australia Party organisational bodies. He was present at meetings that established the Council of the Institute of Public Affairs in September 1942. The IPA became the peak non-Labor political fundraising body in Victoria and took over the work of the old National Union and developed into a key research and policy formation unit. Menzies also gained political prominence as leader of the ‘National Service Group’ in parliament. This group of UAP backbenchers sought to convince the Opposition led by Fadden and Hughes to take a harder line with Curtin’s Labor government to secure conscription.

During his period on the back bench, Menzies gained undeserved notoriety over the ‘Brisbane Line’ controversy. In 1942, Minister for Labour and National Service, Eddie Ward, claimed that Menzies, when Prime Minister, had proposed abandoning northern Australia above a ‘Brisbane Line’ to the Japanese in the event of invasion. Menzies vigorously defended his own and his government’s reputation over this accusation, but rumours persisted.

In the lead-up to the 1943 federal election, divisions appeared in Opposition ranks. Menzies publicly rejected Opposition leader Arthur Fadden’s proposal for a scheme of postwar tax credits, saying the country simply could not afford it. On election day, 21 August 1943, the Curtin government was returned with the most comprehensive 2-chamber victory achieved by any party since Federation.

In the recriminations following the decrease of Opposition numbers, the Country Party–United Australia Party alliance was questioned. The lacklustre leadership provided by William Hughes was challenged and on 22 September 1943, Menzies was re-elected leader of the UAP.

Leader of the Opposition 1943–49

Menzies immediately ended the United Australia Party’s alliance with the Country Party. As leader of the largest non-government party in the House of Representatives, he now assumed the role of Leader of the Opposition. Internal reports into the UAP electoral defeat acknowledged that the party, born out of the peculiar political circumstances of the Depression, had long since lost its unity and sense of direction. The number of independent anti-Labor candidates who stood at the 1943 election was a clear indication of this.

The creation of a new anti-Labor party, with a new structure and a new name, was the solution proposed. It was argued that only a new party representing genuine liberalism could unite the dispirited anti-Labor forces and act as an effective alternative to Labor’s socialism.

Menzies took a leading role in the creation of what would eventually become the Liberal Party. He was not its sole inspiration, nor its only leading light. Nor was his position as federal parliamentary leader of the new party completely secure in the early years. Menzies did, however, help produce the first draft of the new party’s constitution. At a conference in Canberra in October 1944, he used a paper entitled ‘Looking forward’, by Charles Kemp, economic adviser to Victoria’s Institute of Public Affairs, to argue the direction the new party should take. At the end of the party’s second convention, held in Albury in December 1944, Menzies was appointed a member of its provisional Federal Council and chairman of its policy committee.

The new party was to have a federal structure, with a permanent secretariat to do research and assist the federal parliamentary party. State organisations would be under the control of elected state councils and the Federal Council would comprise one representative from each state organisation plus the 2 federal parliamentary leaders. Under a deal Menzies arranged with the powerful Australian Women’s National League, women would be guaranteed representation on the state executive.

Most important of all, the new party would raise and control its own funds, distancing itself from the charges constantly laid against the United Australia Party, that it was the party of big business. At the inaugural meeting of the Federal Council held in Sydney in August 1945, the Liberal Party formally came into being.

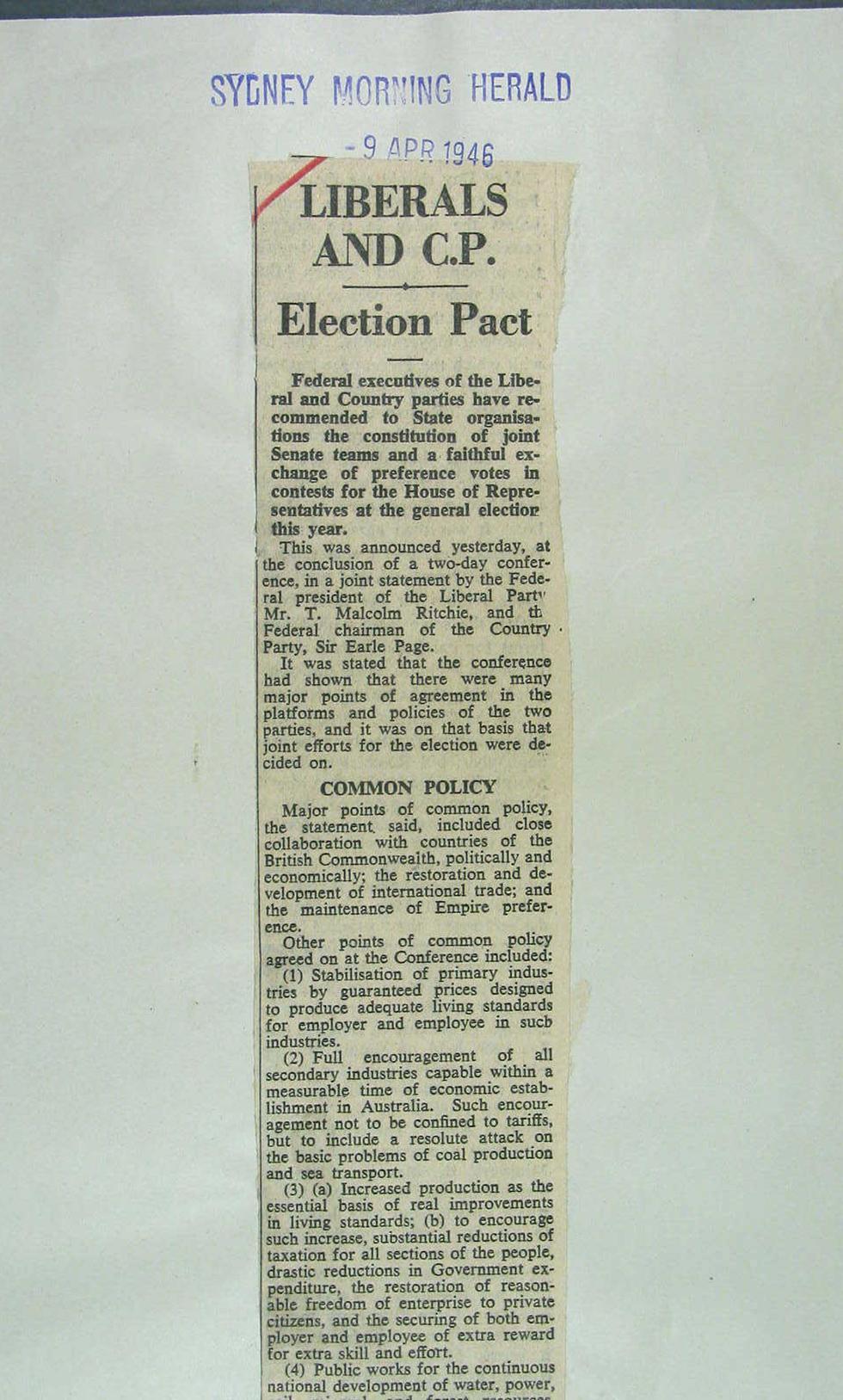

The Liberals had high hopes of doing well in the 1946 federal election. The Labor Party, led by Ben Chifley, seemed less unassailable than it had during the war. The coming of peace had changed the political climate. Many Australians were eager to throw off wartime restrictions and controls. But, on election night 28 September 1946, Labor was returned, with a slightly reduced majority in the House of Representatives and an overwhelming majority in the Senate. It was the first time since Federation that Labor had won successive federal elections. With his leadership of the federal parliamentary party once again under question, Menzies contemplated leaving politics.

The threat of bank nationalisation gave Menzies a renewed determination to stay on as Liberal leader. In 1945, the Chifley government had legislated to reform the banking sector and bring it under tighter government control. The government-owned Commonwealth Bank became the nation’s central bank. The bank’s board was replaced with a single governor directly responsible to the federal treasurer. The bank also retained its wartime powers to set interest rates and control the flow of money. The Banking Act also contained provisions requiring federal, state and local governments, and their instrumentalities, to use government-owned banks.

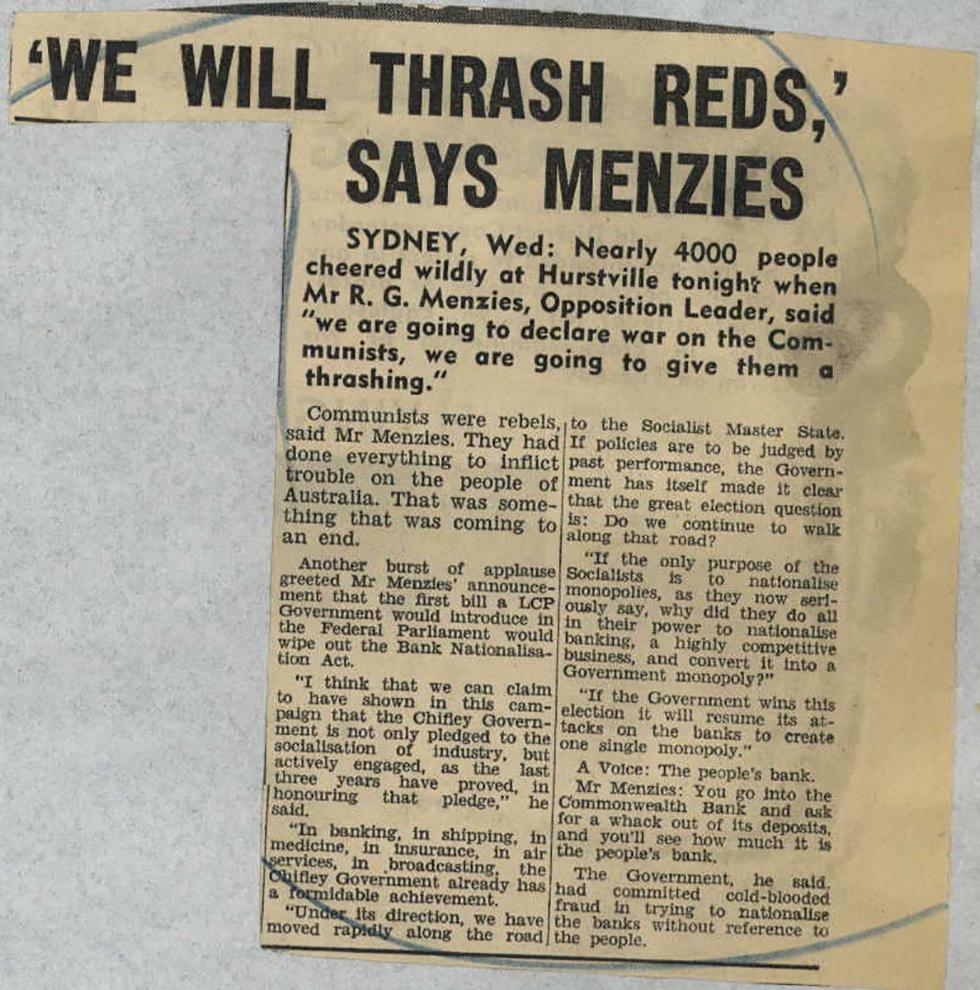

In May 1947, the High Court ruled this last provision unconstitutional. Fearing that all its banking legislation was now under threat, Labor proposed to nationalise Australia’s private banks. In an atmosphere of mounting crisis, legislation providing for bank nationalisation was passed, then immediately challenged before the High Court. The Liberal Party and the United Bank Officers Association organised a series of protest meetings at which Menzies declared ‘war’ on Labor’s socialist agenda.

In 1948, the High Court ruled that nationalisation was beyond the powers of the federal government, a view confirmed on appeal a year later by the Privy Council in London. The vigorous and ultimately successful fight Menzies put up against bank nationalisation cemented his position as federal parliamentary leader of the Liberal Party.

In the lead-up to the 1949 federal election, Menzies campaigned on the portrayal of the Labor Party as out of touch with Australia’s postwar aspirations. He was helped by Chifley’s determination to contain union wage demands and control inflation. Particularly damaging for Labor was a Communist-led coal strike in New South Wales, and the government’s use of troops to restore essential supplies. Menzies went to the electorate with the promise to control Communism, extend child endowment, counter inflation and end wartime petrol rationing. Chifley simply said Labor would stand on its 8-year record.

An electoral redistribution before the election increased the number of seats in the House of Representatives from 74 to 121, and Senate representation increased from 36 to 60. The Opposition was able to take full advantage of the absence of sitting members in these new seats. It was a close-fought campaign, but on election day 10 December 1949, Menzies and the Liberal Party emerged victorious.

In the Liberal Party's first election campaign, Robert Menzies set out an enduring coalition with the Country Party. NAA: A5954, 2340/4, p.4

The Menzies era 1949–66

On 19 December 1949, Menzies was sworn in as Australia’s Prime Minister for the second time. He celebrated his 55th birthday the following day. In light of the humiliations he had suffered in 1941, his re-election to the office marked one of the most astonishing comebacks in Australian political history. Rejected by his own party, Menzies had been forced to resign as Prime Minister and leader of the United Australia Party in 1941. He had used his years out of office to refine his political philosophy and help build a new political party, the Liberal Party.

In 1949, Robert Menzies' Liberal-Country Party Coalition won government, championing the anti-Communist cause. NAA: A5954, 2315/13, p.15

The 1949 federal election supplied Menzies with a substantial majority of 27 seats in the newly expanded House of Representatives, but the Labor Party controlled the Senate. Menzies had learned from his first period as Prime Minister. This time he tempered his arrogance and restrained his overbearing manner with colleagues. At the same time, he was determined to maintain a firm hand with internal Liberal Party dissidents and do whatever was necessary to ensure unity with the Liberals’ minority coalition partner, the Country Party.

The new ministry comprised 13 Liberal and 5 Country Party ministers. The Liberal ministers were Eric Harrison (Defence, and Post-war Reconstruction), Harold Holt (Labour and National Service, and Immigration), Percy Spender (External Affairs, and External Territories), Richard Casey (Works and Housing, and Supply and Development), Philip McBride (Interior), Senator Neil O’Sullivan (Trade and Customs), Senator George McLeay (Shipping and Fuel), Thomas White (Air, and Civil Aviation), Josiah Francis (Army, and Navy), Senator John Spicer (Attorney-General), Enid Lyons (Vice-President of the Executive Council), Senator William Spooner (Social Services) and Oliver Beale (Information, Transport, and Supply). The 5 Country Party ministers were Arthur Fadden (Treasurer), John McEwen (Commerce and Agriculture), Earle Page (Health), Hubert Anthony (Postmaster-General) and Senator Walter Cooper (Repatriation).

Barely 6 months after Menzies returned to office, Australia was at war in Korea. After units of the North Korean People’s Army crossed the 38th parallel and invaded the Republic of Korea on 25 June 1950, President Harry S Truman ordered United States military forces to assist the Republic of Korea. The United Nations Security Council passed a resolution urging UN members to give military support to South Korea.

Within a month, Australian ground troops had been committed to the conflict. In the privacy of Cabinet, Menzies conceded that while the electorate was being told Australian troops were being sent to assist the United Nations, in fact they had been committed to secure Australia’s relationship with the United States. Eventually 3 infantry battalions, 1 RAAF fighter squadron, 1 aircraft carrier, 4 destroyers and 4 frigates served in Korea, although not all at the same time.

Menzies had the good fortune to gain office just as the previous Chifley government’s postwar economic reforms were beginning to bear fruit. His government also benefited from the economic stimulus provided by the Korean War and the postwar mass migration program, a scheme the Menzies government warmly embraced. Annual factory production in Australia rose from £489 million in 1949 to £1843 million in 1959. This, combined with generally strong commodity prices and high export earnings, was the foundation for the ‘long boom’ of the Menzies years.

But there were problems. One of the Liberal Party’s promises at the December 1949 election had been to ‘put value back into the pound’. The new government proved reluctant to confront inflation. The 2 measures economists at the time recommended – a tax on wool sales (wool prices soared during the Korean War) and an appreciation of the Australian pound (then worth 16 shillings sterling) – were unacceptable to Menzies’ Country Party coalition partners. It was not until late 1951 that action was finally taken – a ‘horror budget’ with a 10% income tax increase and increases also in company tax, sales tax and customs and excise.

An unwillingness to respond quickly to adverse economic developments and ‘stop–go’ management of the economy characterised Menzies’ second term as Prime Minister. The government faced a rapidly growing economy, with consequent inflationary pressures. For ministers and economic advisers who had previously only experienced depression and war, coping with a booming economy must have appeared a welcome difficulty. Certainly Menzies’ own instinct was not to interfere with economic growth. Unfortunately, when the economy threatened to overheat, the delayed government intervention was necessarily sudden and sharp. The ‘long boom’ of the Menzies’ years was thus punctuated with ‘horror budgets’ in 1951 and 1956, and a severe ‘credit squeeze’ in 1960.

The use of monetary policy, which allowed fine-tuning of the economy, eventually became the Menzies government’s preferred means for exercising economic control. To do this, the banking system had to be reformed and an independent central bank created. This was a long drawn out process. Coalition infighting and Labor opposition, both aimed at protecting the Commonwealth Bank, delayed matters for most of the 1950s. Menzies was reluctant to press the issue, so various proposals were considered and a succession of bills introduced. It was not until 1959 that the Reserve Bank of Australia was established.

Communism and espionage

During the 1949 federal election campaign, the Liberals had promised to outlaw the Communist Party of Australia. The Communist Party Dissolution Bill, introduced into the House of Representatives on 27 April 1950 was one of the most contentious pieces of legislation ever placed before an Australian parliament. Its main provisions made the Australian Communist Party and associated organisations unlawful and appointed a receiver to dispose of their property. Members of the Communist Party were to be ‘declared’, making them ineligible for Commonwealth employment, holding office in a trade union, or working in a defence-related industry. Although a ‘declared’ person could appeal to the High Court, the onus of proof was reversed, making it necessary for them to prove they were not communists.

Unease amongst civil libertarians increased when Menzies later admitted to errors in the names of some of the 53 Communist Party members he read out to parliament during his speech introducing the Bill. The Bill passed the House of Representatives, but ran into trouble in the Labor-controlled Senate. Labor senators agreed that the Communist Party should be dissolved, but were determined to force amendments connected with ‘declaring’ and the onus of proof. The Federal Executive of the Labor Party eventually intervened and directed the party in the Senate to withdraw its opposition to the legislation. The Bill was eventually passed without amendment on 19 October 1950.

The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 was immediately the subject of legal challenge. In March 1951 the High Court, by a majority of 6 to 1, declared the Act unconstitutional and therefore invalid. Menzies’ response was a double dissolution election to give the government control of the Senate, with a referendum to alter the Constitution to follow. The Banking Bill, already rejected once by the Labor-controlled Senate, provided the trigger for a double dissolution.

The double election was set for 28 April 1951. In his campaign speeches, Menzies identified the Korean War and the Communist threat as the key election issues. Labor leader Ben Chifley chose to campaign on the government’s failure to deal with inflation. There were a few noisy meetings – the Brisbane Town Hall gave Menzies his usual rowdy reception – but most journalists thought voter apathy, mixed with unease, best characterised the election. The coalition was returned with a slightly reduced majority of 17 seats in the House of Representatives, but with control of the Senate.

The referendum campaign over the Communist Party Dissolution Act got underway in late August 1951. The Federal Executive of the Labor Party decided to throw its weight behind a ‘No’ vote. The new Opposition leader, HV (Bert) Evatt, campaigned vigorously. He warned voters that Menzies wished to establish a police state in Australia. Menzies himself encountered some of the rowdiest and most violent meetings in federal campaign history. It did not help that his presentation of the ‘Yes’ case was not clear. He had particular difficulty explaining how denying the civil liberties of otherwise law-abiding citizens simply because they held different political beliefs protected the basic freedom of all. That some Liberal Party members and conservative Anglican churchmen openly challenged the government’s proposals did not help his case either.

The referendum, held on 22 September 1951, failed. The states split down the middle (3 ‘Yes’ and 3 ‘No’). Out of the 4.7 million votes cast, the ‘No’ case obtained a narrow 58,000 vote majority. The margin was less than the 66,500 informal votes cast. Faced with a proposal for constitutional change, a majority of the electorate decided to continue the status quo and vote ‘No’. What is significant about the result is that, despite the controversial and extreme nature of the proposals, the vote was so close.

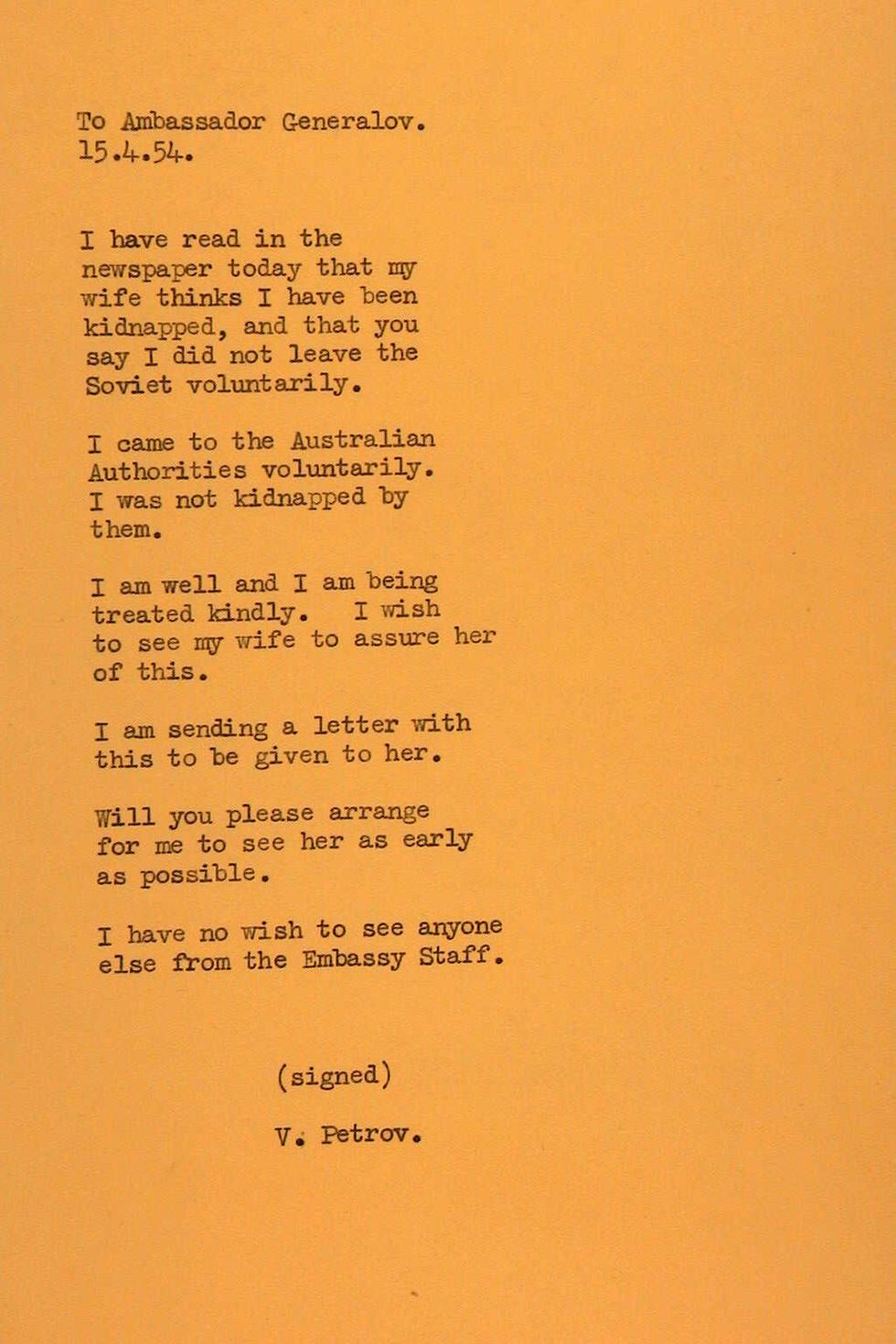

The intense response to the attempt to outlaw the Communist Party surfaced again in 1954. On the eve of a federal election, Menzies was informed that Vladimir Petrov, a Soviet Embassy official and self-confessed spy, had defected, bringing with him evidence of a ‘spy ring’ in Australia. It was an electoral gift to the government. Despite the euphoria of the Queen’s visit at the beginning of 1954, the coalition expected to struggle at the polls. Menzies was careful not to overplay his hand, but his coalition partners were not nearly so scrupulous, dropping hints about Labor involvement in the ‘spy ring’. Despite most voters favouring the Labor Party on a 2-party preferred basis, the government was returned with a narrow 7-seat majority in the election on 29 May 1954.

When Soviet Embassy officials Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov defected to Australia in April 1954, a Royal Commission investigated Soviet espionage in Australia. NAA: A6227, p.66

In the wake of the defection of both Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, Menzies established a Royal Commission to investigate espionage in Australia. The commission did not produce any evidence that warranted bringing charges, but it did succeed in damaging the reputations of a succession of journalists, trade unionists, Communists and Labor Party members who were called before it to give evidence. Opposition leader HV ‘Doc’ Evatt and some Labor supporters came to believe that the whole affair amounted to a conspiracy aimed at tarnishing his reputation and keeping Labor out of office.

Evatt insisted on representing two of his staff members who were named in evidence before the Royal Commission. His increasingly erratic behaviour and inability to distance himself personally from the proceedings, led to the commissioners eventually banning him from further appearances.

The pressure of events took its toll. On 19 October 1955, Evatt opened debate in the House of Representatives on the Petrov Royal Commission’s final report. He announced that he had written to the Soviet Foreign Minister, VM Molotov, who had assured him that the Petrov documents were false. The reaction of Labor members was stunned silence, while the government benches exploded in derisive laughter.

Menzies’ reply a week later was devastating. In prime radio time, he ruthlessly and scornfully destroyed Evatt’s argument and credibility over the issue. The personal hatred that the two men felt towards one another was apparent to all. As the debate wound up, Menzies announced an early federal election for 10 December 1955. To no one’s surprise, the government was returned with an increased 28-seat majority. Evatt remained leader of the Opposition until 1960, but was never again a serious challenge to Menzies.

The Petrov affair was the final catalyst for a split in Labor Party ranks. Evatt’s appearance before the Petrov Royal Commission outraged many Labor anti-Communists, while other party members accused the mainly Catholic anti-Communist faction of being disloyal, and being directed by outside organisations. After months of accusation and counter-accusation, the right-wing anti-Communists, dubbed the ‘Groupers’, were expelled from the Labor Party in March 1955. In following years, the split spread to the State Labor parties in New South Wales and Queensland. This outcome also reflected the influence of BA Santamaria's 'The Movement', later the National Civic Council.

The various breakaway groups later joined to form the Democratic Labor Party. The DLP’s fierce anti-Communist stance and bitterness towards the Labor Party helped keep Labor out of federal office for the next decade and a half.

Parliament and public service

Although Menzies’ dominance of Australian politics in the 1950s and early 1960s benefited from the misfortunes that befell the Labor Party and his good luck in coming to power as the economy began to pick up, Menzies also had considerable skill as a politician. He was one of the first federal party leaders who actively targeted women’s votes. Identifying women as usually more conservative in their voting habits than men, Menzies was always careful to emphasise how issues like industrial relations and defence were of concern to women.

Menzies’ deployment of the ‘Communist bogey’ was masterful. He genuinely believed that Communism posed a real threat to Australian society, both at home and abroad. He raised the threat of Communism before each election, provoked Opposition disarray and scared the more impressionable voters back to supporting the coalition. Menzies was helped in this tactic by the fact that many recent immigrants were refugees from Eastern Europe who harboured deep fears of Communism.

The early poll was another tactic that Menzies used to great advantage. 3 of the 7 federal elections he called during his second period as Prime Minister were held at least 12 months ahead of time. In 1951, an early double dissolution election enabled the coalition to gain control of the Senate. In 1955, an early election was called to take advantage of HV Evatt’s embarrassing blunders over Petrov and the disarray that the ‘split’ had caused in Labor ranks. And in 1963, an early election enabled the government to use good economic news to repair the damage it had suffered at the previous election.

On the floor of the House, in the big parliamentary debates and in Prime Minister’s question time, Menzies dominated proceedings. He was a forceful speaker and a talented parliamentary debater. He displayed, in fact, many of the characteristics of the leading barrister that he had once been: a ready wit, a clear analytical mind and a superb command of language. He spoke with a clear, strong baritone voice. Menzies also had a commanding physical presence. He was tall, large-framed, with a handsome face, a full head of white hair and bristling black eyebrows. Clyde Cameron, a Labor opponent, said of him: ‘He looked like a PM, he behaved like a PM and he had the presence of a PM’. Of the many political opponents Menzies faced during more than 30 years in Federal Parliament, it was said that only John Curtin and Gough Whitlam seemed ever to match him in debate.

Menzies was the last Prime Minister of Australia to hold office in an era when the public meeting and the radio broadcast were the primary means of communicating with the electorate. In public, he was not a charismatic orator in the mould of Britain’s Winston Churchill, or a fiery demagogue like New South Wales Labor leader Jack Lang. He was a forceful and effective public speaker nonetheless. For campaign meetings, Menzies’ usual tactic was not to prepare a set speech, but speak to a few points he would note down in pencil beforehand. Parliament and major campaign meetings were broadcast live. For the radio audience at home, Menzies’ strong, measured voice, with the clamour of hecklers around him, had the effect of drawing the listeners to him, evoking both sympathy and intimacy.

He was often at his best before a hostile audience. His quick wit and dry humour helped him respond to interjections. Menzies’ response to being counted out by unionists at Brisbane Town Hall in 1951 was: ‘they get marks – [spelling out] M A R X – for this in Moscow you know’. And his rejoinder to ‘I wouldn’t vote for you if you were the Archangel Gabriel’ yelled by a heckler at Williamstown, Melbourne in 1954 was just as memorable: ‘If I were the Archangel Gabriel, I’m afraid you wouldn’t be in my constituency’.

Following the Liberals’ 1955 federal election victory, Menzies announced a significant change in ministerial arrangements. He increased the number of ministers from 20 to 22. He created a division between the 12 senior ministers who sat in Cabinet and the junior ministers who did not sit in Cabinet. Included in the ‘inner’ ministry were Paul Hasluck (Territories) and William McMahon (Primary Industry, and Social Security). In the outer ministry were Archie Cameron, Charles Davidson, Frederick Osborne, Norman Henty and Allen Fairhall. The changes were partly to fulfil backbench ambitions, but also to improve efficiency in government. This was not the first time Menzies had introduced reforms aimed at improving Cabinet efficiency. In 1951 he had streamlined the way Cabinet submissions were presented and dealt with. In 1954, he had unsuccessfully experimented with the division of Cabinet into 2 teams, those ministers concerned with policy and those concerned with administration.

Achieving efficiency was also behind Menzies’ move to accelerate the relocation of public servants and their departments to Canberra. Depression and war had stifled the development of Australia’s national capital. Under Menzies, Canberra’s growth was accelerated. A National Capital Development Commission was created in 1957, and by 1958, the first public servants were beginning to arrive in Canberra from Melbourne (the Department of Defence was the first of the big departments to move). The city’s population grew from 28,000 in 1954 to 93,000 by the time Menzies retired in 1966. Menzies also completed some elements of the original plan for the national capital, most notably the construction of Lake Burley Griffin, completed in 1964.

The benefit society and the individual derived from a sound education was one of the cornerstones of Menzies’ self-belief and political philosophy. In the late 1950s, he began to take an active interest in the ailing state of Australia’s universities. He commissioned Keith Murray, a distinguished British scholar and higher education administrator, to inquire into the state of Australia’s universities. The 1957, Murray Report provided the blueprint for wide-ranging reform of the university system. There was an increase in recurrent grant funding to universities, and Commonwealth funds were made available for capital expenditure. Then in 1964, the Martin Report recommended the creation of a ‘binary’ system of higher education with universities and colleges of advanced education providing for separate educational needs in the community. Nor did Menzies ignore primary and secondary education needs. His government made a Commonwealth commitment to provide state aid to non-government schools in 1963.

Trade and international affairs

In January 1956, Menzies announced the creation of a new Department of Trade. Deputy leader of the Country Party, John McEwen, was given charge of the portfolio. Over the following years, and with Menzies’ strong support, McEwen negotiated key bilateral trade agreements (starting with the United Kingdom and Japan in 1956) to boost Australia’s export earnings. Such trade agreements characterised trade policy in the later years of the Menzies government.

In 1961, the British government announced plans to apply to join the European Economic Community. Duncan Sandys, British Minister for Commonwealth Relations, visited Australia as part of the consultative process with Commonwealth nations. Menzies was concerned about the British proposal. There were adverse trade implications, as Australia benefited from a system of imperial trade preferences with the United Kingdom. He also thought the move would weaken the Commonwealth. At the September 1962 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in London, Menzies and old and new Commonwealth leaders, made clear their disappointment, to no avail. However, France vetoed Britain’s application and Britain was not admitted to the common market until 1973. By then, Australia was no longer dependent on Britain as a market for its goods.

Menzies was the first Australian Prime Minister since William Hughes to achieve a significant presence on the world stage. His many overseas trips, combined with his long tenure in office, meant that he was well known to many world leaders. Menzies’ easy charm also helped him forge close relationships and he was friends with British prime ministers Winston Churchill (the prickly relationship of the early war years forgotten) and Harold Macmillan. Menzies was also respected by both Republicans and Democrats in Washington, where he was admired for his anti-Communism, firm advocacy of democratic values and consistent support of the United States.

The Menzies government oversaw significant regional developments in its early days: the Colombo Plan in 1950, the ANZUS Treaty in 1951, and membership of the South East Asian Treaty Organisation in 1954. Then in the mid-1950s, with his political ascendancy at home secure much to the annoyance of Richard Casey, Menzies began to take a more active interest in international affairs. In 1960–61 following Casey's retirement as Foreign Minister, he was both Prime Minister and Minister for External Affairs.

Not all Menzies’ initiatives on the world stage were successful. During the 1956 Suez crisis, for instance, he was asked by the British to lead an international delegation to persuade Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser not to proceed with nationalisation of the Suez Canal. Menzies’ legalistic approach to the issue, and his inability to appreciate Egyptian interests and outlook, contributed to the failure of the talks. When Britain and France invaded Egypt 2 months later in a disastrous attempt to seize back control of the canal, Menzies (who had been kept in the dark about the plan) called it a ‘proper’ response. Critics were quick to accuse him of supporting British ‘gunboat diplomacy’. This was all a great embarrassment to the Menzies.

Robert Menzies chaired the Suez Canal Committee to present a case for United Nations control of the Canal, to the Egyptian government. NAA: A1209, 1957/4055, p.7

In 1960, Menzies addressed a special meeting of the General Assembly of the United Nations. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had called the meeting following his breaking off of disarmament talks with the West. Menzies’ political opponents unfairly claimed that his appearance at the UN was a ‘humiliation’ for Australia, saying he was insensitive to third-world opinion and diplomatically inept. In fact, it was Menzies, in a private meeting with the Soviet Premier, who was able to convince Khrushchev that Britain and the US wished for an accommodation with the USSR, and that disarmament talks should resume.

More than any Australian Prime Minister before or since, Menzies championed the 'Old' Commonwealth. He attended all 10 Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings held during his years in office. By the 1960s, he was the Commonwealth’s unchallenged elder statesman. Privately Menzies questioned the ability of newly independent members of the Commonwealth to be the equal of the old white self-governing dominions where British stock and British values prevailed. He never embraced ‘the winds of change’ that British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan recognised were blowing through the former colonies of Africa.

When South Africa’s apartheid policies threatened to split the Commonwealth in the early 1960s, Menzies advocated ‘non-interference’ on the grounds that it was an internal matter. His position was undermined when Britain suddenly abandoned ‘non-interference’ and supported a 1961 United Nations resolution condemning South Africa’s racial policies. For Menzies, it was yet another example of Britain’s eagerness to placate the ‘new’ Commonwealth countries at the cost of its older friends. It was also an indication that Menzies' views were increasingly old fashioned.

Although critics were fond of portraying Menzies as an extreme Anglophile, ‘British to his bootstraps’, he was never an uncritical supporter of Britain. He was also enough of an Australian nationalist to be sometimes deeply offended by British high-handedness. Menzies told family and friends that ‘You’ve got to be firm with the English. If you allow yourself to be used as a doormat they will trample all over you’.

The monarchy

Some of Menzies’ ‘Britishness’ centred around his admiration of the British monarchy, and in particular his deep personal regard for Queen Elizabeth II. Menzies had first met the young Princess before World War II, and their paths crossed many times in subsequent years. Both shared a passion for home movie making, and the earliest footage of Princess Elizabeth was taken by Menzies. After the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, both formal and informal meetings between the 2 were a regular event. Their relationship was cemented during the young Queen’s long tour of Australia in 1954.

The Queen’s regard for Menzies was revealed when she conferred a personal knighthood on him during her visit to Australia in March 1963. Unlike other Royal titles, the awarding of which is recommended by a head of government, membership of the ‘Most Noble Order of the Thistle’, second only to the Order of the Garter, was given in recognition of the personal esteem of the reigning monarch and has only 16 members. Menzies, who was on record as saying that it would be improper for a serving Prime Minister to accept a knighthood, was not consulted before the announcement and had no choice but to accept the Queen’s gift. Menzies was further honoured in 1965, when he was awarded an even rarer ceremonial title, Constable of Dover Castle and Warden of the Cinque Ports.

Defence

Despite Menzies’ concern about the Communist threat abroad and at home, military spending was given a low priority. Annual defence expenditure declined from 4.9% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1953, the last year of the Korean War, to 2.5% of GDP in 1964. A national service scheme was introduced in 1951 whereby all 18-year-old males underwent 3 to 6 months of military training. This was abandoned in 1959, on the grounds that modern warfare no longer required large numbers of partially trained soldiers.

Throughout the Menzies years, the government pursued a policy of forging strong defence links with Britain and the United States. Menzies agreed in 1950 that Britain could test nuclear weapons in Australia, and use the Woomera rocket range in South Australia to develop its Blue Streak missile. Beginning in 1950, Australia committed troops to assist the British in Malaya and later cooperated in establishing ANZAM, a joint command structure in the area. As Britain gradually withdrew west of Suez, however, the Menzies government increasingly focused its defence thinking on its ANZUS partner, the United States. Menzies supported the American commitment of troops to Indochina and, beginning with North-West Cape in 1963, allowed US communications and satellite control bases to be built in Australia.

In 1962, Australia sent its first Special Forces military advisers to South Vietnam to assist in the training of South Vietnamese government troops. On 10 November 1964, Menzies announced the introduction of a new scheme for peacetime conscription by which 20-year-old males were chosen by a ballot of birth dates to serve for 2 years in the Australian Army. This included overseas service, and at the time seemed to herald a possibility of substantial commitment of troops to assist the United States in Vietnam.

The Menzies government announced its intention to send military advisers to South Vietnam in May 1962 and the first training team arrived in August 1962. NAA: A1209, 1962/708, p.2

6 months later, on 29 April 1965, Menzies announced that a battalion of Australian combat troops were to be sent to South Vietnam in response to a request from the South Vietnamese government. What Menzies did not say was that his government had approached the United States requesting such an invitation. There had been no prior invitation from the South Vietnamese government. The size of the Australian commitment reached a peak of 8000 in 1967.

Retirement

On 20 January 1966, Menzies announced his resignation as Prime Minister of Australia. He was 71 years of age. Over 2 periods, Menzies had served as Prime Minister for a total of 18 years 5 months and 10 days. He is still Australia’s longest-serving Prime Minister. On 26 January 1966, he handed the reins to Harold Holt, deputy leader of the Liberal Party – the man Menzies still called ‘Young Harold’ after his 30 years in parliament.

Sources

- Hughes, CA, Mr Prime Minister: Australian Prime Ministers, 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1976.

- Martin, Allen, ‘Sir Robert Menzies’ in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australia’s Prime Ministers, New Holland Press, Sydney, 2001.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Cables to and from Mr Menzies during visit to London, 1941, NAA: CP290/9/1, 15

- Prime Minister’s Office file on Royal Commission on Espionage, 1954–55, NAA: A6227