Robert Gordon Menzies was born in rural Victoria in 1894. He went to primary school in Ballarat, then to high school at Wesley College in Melbourne. He graduated in law from the University of Melbourne in 1916, and became a barrister in 1918. His appearance before the High Court in the Engineers’ Case in 1920 established his reputation as a barrister.

In 1928, Menzies entered the Victorian parliament and, in 1935, Federal Parliament. He was Attorney-General in the Lyons government, and won the United Australia Party leadership after Lyons’s death in 1939. He became Prime Minister for the the first time on 26 April 1939.

Growing up

Menzies was born at Jeparit, a tiny township in the Wimmera, in north-western Victoria, on 20 December 1894. He was the fourth of 5 children born to James and Kate Menzies. His parents ran a struggling general store in the town, and the family lived in rooms built at the back of the store. With his sister and 3 brothers, Menzies enjoyed the normal pursuits of childhood in a small country town. They played football and hockey, hunted yabbies, and fished and swam in the Wimmera River or nearby Lake Hindmarsh. For their parents, it was a dour struggle for economic survival.

The Menzies children grew up in a pious household. Their father’s sense of duty led him into local politics and community affairs. He was a long-serving member of the Dimboola Shire Council and twice held the office of shire president. He represented the local electorate of Lowan in the Victorian Legislative Assembly between 1911 and 1920.

Formal education for the Menzies children began at the local Jeparit school. They were then sent to Ballarat where they boarded with their grandmother, Elizabeth Menzies, and attended the Humffray Street state school. The school’s upper sixth ‘scholarship’ class had a statewide reputation for excellence.

At the Humffray Street school, Menzies’ academic ability came to the fore. He completed his final 2 years of primary school education and, at the end of 1907, topped the state in the scholarship examination. With publicly funded secondary schools yet to be established in Victoria, winning one of the 40 scholarships on offer to state school students was the only way pupils of limited means could hope to attend one of Victoria’s private secondary schools.

Menzies then went to Grenville College in Ballarat. At the end of his second year, Menzies performed poorly in the public examination for the ‘leaving certificate’. As his father expected to be elected to the Victorian Parliament, the family moved to Melbourne.

In 1910, instead of enrolling at Scotch College as his father instructed, Menzies joined friends enrolling at Wesley College. His contemporaries there recall a tall, gangling boy with ‘intense energy and tremendous self-assurance’ who never stopped talking. He could be scornful, and ‘You’re a dag’ was his usual response to those with whom he disagreed. The nickname ‘Dag Menzies’ stuck with him throughout his schooldays.

Menzies’ academic performance during his first 2 years at Wesley was not outstanding. During his third and final year, however, he gained the top marks in the English and History examinations, and won one of the 25 exhibitions awarded by the state for university study. Menzies credited 2 teachers at Wesley, Harold Stewart and Frank Shann, with helping him achieve the result. His own self-discipline and single-minded determination were also factors in his success.

Law student 1913–18

In 1913, Menzies enrolled in first-year law at the University of Melbourne, where he continued to shine. He won university prizes and exhibitions in history, jurisprudence and law, and the coveted Bowen Prize for an English essay. He also took a leading role in student affairs, serving as president of the Students’ Christian Union, editor of the Melbourne University Magazine and president of the Students’ Representative Council.

For the first time, Menzies’ political views found public expression. He showed himself to be a mainstream liberal-conservative: an empire loyalist, an advocate of wartime conscription, a defender of free speech and a supporter of free enterprise.

In 1916, Menzies graduated with first-class honours in his Bachelor of Laws degree. He was awarded the Master of Laws in 1918.

Menzies’ university years coincided with the First World War. As a prominent undergraduate, he had declared himself a patriotic supporter of the war and an advocate of conscription for overseas service. He had also undertaken compulsory military training, serving 4 years with a part-time militia unit, the Melbourne University Rifles (1915–19). He appears to have enjoyed his taste of military life and was commissioned a lieutenant in the Rifles.

Unlike many of his male contemporaries and despite his support for conscription, Menzies did not enlist in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) for overseas service. He never explained the reasons for not enlisting, although in later life it hurt him politically. His 2 elder brothers, Les and Frank, had enlisted in the AIF. The family might have thought that sending 2 of the 3 eligible Menzies brothers to the front was an adequate contribution (Syd, the youngest, was still at school). Perhaps Kate Menzies was determined that her brilliant son should not be risked – on the enlistment issue, she never wavered.

Barrister 1918–28

In May 1918, after completing the required 12 months’ articles of clerkship with a solicitor, Menzies was admitted to the Victorian Bar. He found rooms in Selborne Chambers and obtained the prized position as a pupil to leading barrister Owen Dixon. Menzies quickly built up a solid practice, specialising in constitutional law.

Menzies made his first appearance before the High Court in 1919. A senior counsel had fallen ill and Menzies, although a junior, was offered the brief and won the case. As Menzies’ reputation grew, he appeared more and more often before the High Court, sometimes as Dixon’s junior – they made a formidable combination – but also on his own.

In 1920, Menzies was approached to appear as sole advocate for the Amalgamated Society of Engineers before the High Court. The union sought the right to seek a Commonwealth industrial award for state government employees. The case went to the heart of the issue of Commonwealth versus state rights. The states, with the exception of Labor-governed Queensland, briefed counsel to fight the Engineers. In a series of brilliant moves, over 6 days of argument, Menzies challenged the doctrine of the Immunity of Instrumentalities that limited Commonwealth powers by focusing the Court’s attention on the actual words of the Australian Constitution. The judges, with one dissenting, were persuaded by Menzies’ argument. It was a landmark ruling that had the potential to greatly expand the scope of Commonwealth powers.

The Engineers’ case established Menzies, still a junior counsel, as one of Australia’s leading constitutional lawyers. He later claimed that he ‘got married on the strength of it’. Robert Gordon Menzies and Pattie Maie Leckie married at the Presbyterian Church in Kew on 17 September 1920. Their 4 children were born during the 1920s, the third dying at birth.

Menzies brought to his growing legal practice the same dedication and work ethic that he had displayed as a student. In later years, he was impatient with the claim that his achievements at the bar were due to his innate intellectual gifts. He pointed to hours of hard work studying the brief and detailed preparation of legal argument as the basis of his success. The Melbourne courts might only have sat for 4 to 5 hours a day, but Menzies regularly worked at his desk long into the night – 80-hour weeks were not unknown. In 1929, he took silk and became the youngest King’s Counsel in Australia.

Menzies’ success in the Engineers’ case brought offers of briefs in the area of industrial law. He was involved in much of the litigation surrounding the ongoing maritime and waterfront disputes of the 1920s. In 1926, in an attempt to end the industrial unrest in this key industry, Nationalist Prime Minister Stanley Bruce proposed a constitutional referendum that would give the Commonwealth Arbitration Court power to deal with all industrial disputes, regardless of whether they were interstate or not. Menzies’ knowledge of industrial relations law and his experiences before the Arbitration Court convinced him the proposal would increase rather than end industrial unrest. Although the Engineers’ case had done so much to extend Commonwealth powers, Menzies believed there was an important states’ rights issue to be defended here.

Menzies was persuaded to join with other like-minded conservatives in forming a Federal Union to oppose Prime Minister Bruce’s proposals and campaign for a ‘No’ vote in the referendum. He was among a handful of speakers deployed around the state to address meetings on the issue. It was Menzies’ first taste of political speechmaking. He quickly learned that a politician’s task was very different from that of the barrister. Both had to present a case, but the politician had to take care to speak simply, introduce a little humour and, most important of all, keep repeating the point he wanted to make. He also discovered he was quite good at it and enjoyed the experience.

Politics was in Menzies’ blood. His father and one of his uncles had been members of the Victorian parliament, while another uncle had represented Wimmera in the House of Representatives. Pattie Menzies was also from a strong political background – her father, John Leckie, had held seats in both the Victorian and federal parliaments.

Like his father, Menzies had a strong sense of public duty. What was not inevitable though, is that Menzies’ politics would be conservative. He had a conservative upbringing, but he was no silvertail. Menzies had been a scholarship boy who had risen to prominence in his profession through his own talents. While a schoolboy at Ballarat, he had been regularly exposed to socialist doctrine during visits to his maternal grandfather, John Sampson, a pioneering unionist and Labor man. He would later refer to their long conversations as his earliest political education. Menzies might have been drawn to the anti-Labor side of politics, but he was no arch-conservative. He had a social conscience and a reformist bent.

In 1927, Menzies began to involve himself in the affairs of the Nationalist Party. The Nationalists had been born out of the Labor split and conscription campaigns of World War I. The party was an amalgam of Empire loyalist Labor men, like William Hughes, and representatives of Alfred Deakin’s Liberal Party, the liberal-conservative champions of free enterprise. By the mid-1920s, the party was riven with ideological factions and class division. A shadowy clique of big business interests, the National Union, controlled the party’s funds and tried to dictate policy. Menzies joined with the aim of reforming and revitalising the Nationalist Party.

Victorian parliamentarian 1928–34

In October 1928, Menzies entered the Victorian Legislative Council, having won a by-election for the seat of East Yarra. Within weeks, he was made minister without portfolio in a new minority Nationalist State government, formed when the Labor government had lost the support of the cross-bench Country Progressives.

To ensure the support of the Country Progressives, the incoming Nationalist government agreed to underwrite a bank guarantee for a rural freezing works that had already lost the state over half a million pounds. Menzies and 2 other new ministers resigned in protest. At the December 1929 Victorian State election, Menzies moved to the lower House, successfully contesting the Legislative Assembly seat of Nunawading.

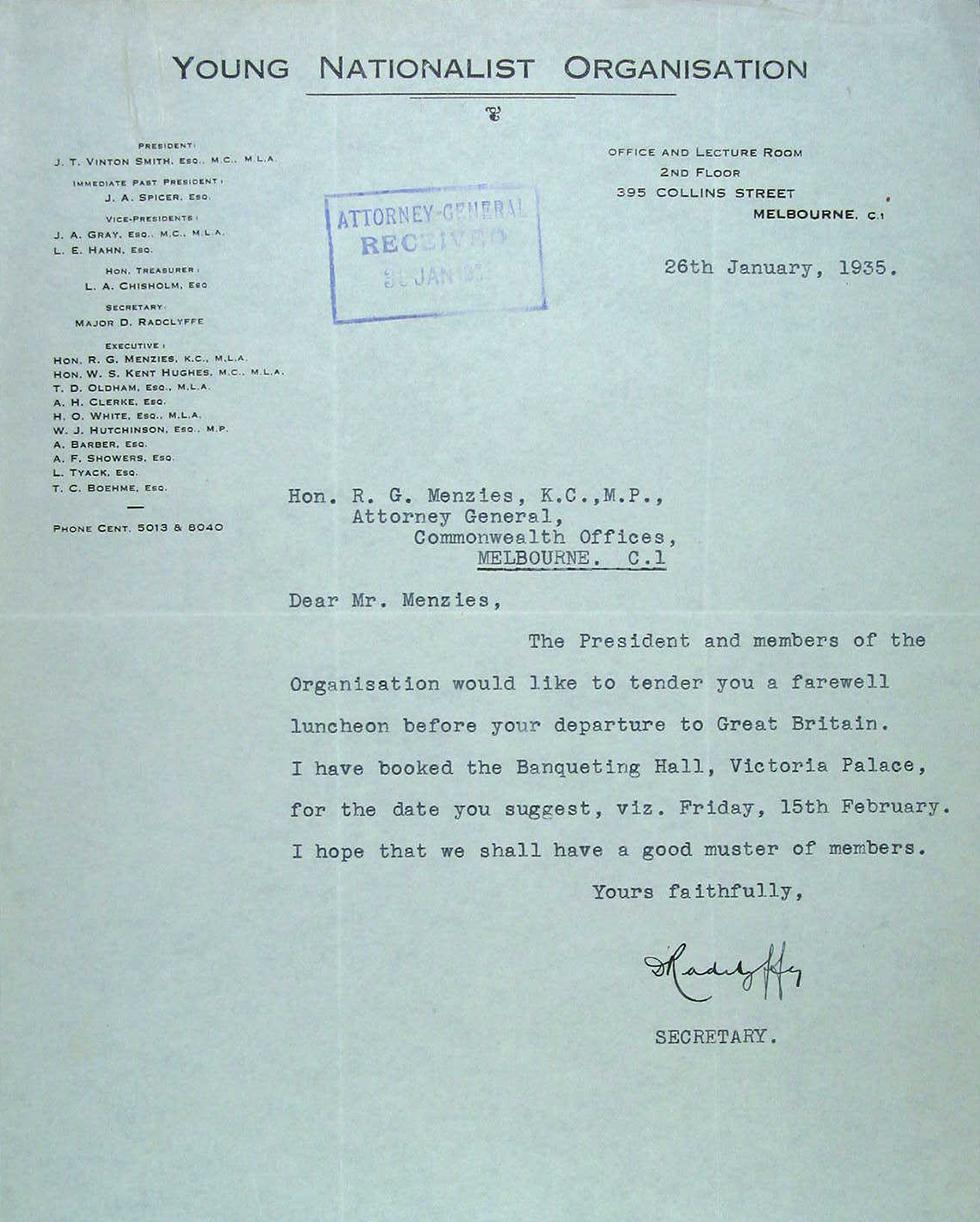

The Young Nationalists farewelled Robert Menzies when he went to London in 1935. With Wilfrid Kent Hughes, Menzies had set up the group to encourage the development of able young speakers in the Nationalist Party. NAA: CP450/7, 74, p.46

Throughout his early years in the Victorian parliament, Menzies was actively involved in internal Nationalist Party matters. In late 1929, he helped establish the ‘Young Nationalists’, a group which sought to revitalise the party by attracting younger men into politics. The party organisation welcomed the move, and Menzies was invited to join the central executive of the National Federation. In what amounted to a ‘Young Nats’ takeover of the State Nationalist Party apparatus, Menzies won the presidency of the Victorian National Federation in September 1931.

Menzies was also drawn into federal political issues. With the onset of the depression of the 1930s, Menzies revealed himself as a firm supporter of economic austerity. In late 1930, he supported Joseph Lyons, acting Treasurer in the Scullin federal Labor government, in his determination to defy the Labor Caucus and meet overseas loan repayments by means of a conversion loan. Menzies was a member of the ‘Group of Six’, mainly Melbourne financiers and businessmen, who organised the successful conversion campaign. In 1931, Menzies and the ‘Group’ were also involved in negotiations that helped Lyons, who had earlier crossed the floor to vote against Labor, become Leader of the Opposition. The Nationalist Party became the United Australia Party with Lyons as its federal parliamentary leader.

In May 1932, the United Australia Party (UAP) won government in the Victorian state election, and Menzies became Victoria’s Attorney-General and Minister for Railways. He was elected deputy parliamentary leader of the Victorian UAP a few weeks later. The railways represented half the state’s public debt, and Menzies was determined they would pay their way. It brought him into conflict with country interests, which sought a reduction in freight rates, and the new road transport industry, which he would seek to regulate and control. Menzies’ years as a Victorian minister were characterised by barely suppressed hostility between the Country Party and himself.

Menzies was appointed acting Premier of Victoria for 3 months in early 1934 when the Premier, Stanley Argyle, was ill. He represented Victoria at the 1934 Premiers’ Conference, greatly impressing Lyons and the other UAP leaders with his easy manner and obvious intelligence. A 2-hour presentation he made about the threat to federalism implicit in the steady increase in the Commonwealth’s financial powers dazzled all who were present. The Melbourne Argus called it a ‘striking analysis’. Everyone agreed that Menzies was destined for greater things.

Commonwealth Attorney-General 1934–39

In 1934, Menzies was approached to stand for the federal seat of Kooyong. The sitting member, Commonwealth Attorney-General John Latham, had announced his intention not to contest the next federal election. After consideration – his family and legal practice would be severely disrupted by a move to Canberra – Menzies reluctantly agreed to stand.

Lyons was eager for Menzies to transfer to Canberra. Among the inducements offered were the position of Attorney-General and a promise that the ailing Lyons would step down before the following election, enabling Menzies to succeed him as Prime Minister. At the federal election, Menzies took the blue-ribbon seat of Kooyong easily, while the Lyons government was returned to office with a reduced majority. After intense negotiations, the United Australia Party and Country Party agreed to form a coalition government.

When the new federal Cabinet was announced, Menzies was named Attorney-General and Minister of Industry. He was almost immediately thrown into the furore surrounding the Egon Kisch affair. Kisch, a European peace activist, had been invited to speak at an All-Australian Congress against War and Fascism in Melbourne in 1934. Believing that he had Communist sympathies, the government had declared him an undesirable immigrant and denied him entry to Australia. To the government, the issue was one of national security. To Kisch’s growing band of supporters, it was about the right to free speech.

A series of sensational developments kept the case in the public eye. Kisch broke his leg while jumping from his ship in Melbourne, and the High Court ruled that the government’s ban had not satisfied the requirements of the Immigration Act. To satisfy such requirements, Kisch was given a dictation test in Scottish Gaelic, which he failed. In turn, the High Court found that Scottish Gaelic was not a European language in the meaning of the Immigration Act. During the Court’s deliberations, Kisch was free on bail and able to speak at public meetings, so the exercise was pointless. In the end, the Commonwealth government was forced into a backdown – it agreed to drop all further legal action and pay all Kisch’s court costs, if he left the country.

Menzies was not involved in the original decision, nor did he have ministerial responsibilities for immigration matters, which lay with the Country Party Minister for the Interior, Thomas Paterson. But throughout the affair, Menzies found himself in the position of being the main defender of government policy. As Attorney-General, the government’s main legal spokesman, it embarrassed Menzies that successive High Court rulings went against the government. The long-term legacy of the affair was that his political opponents could attack Menzies as an opponent of free speech.

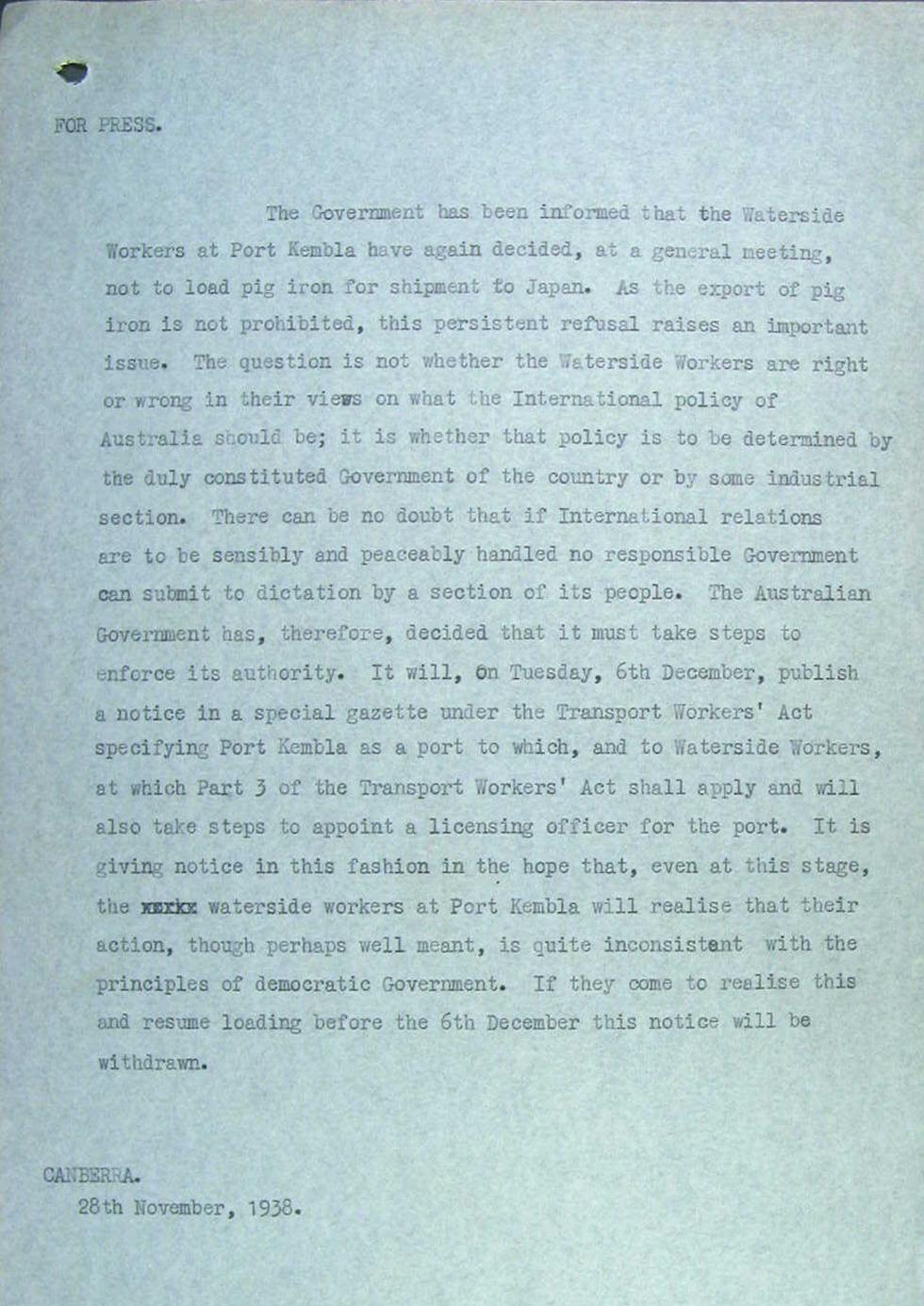

In late 1938, Menzies was again cast into the public spotlight when waterside workers at Port Kembla, New South Wales, refused to load a ship with pig-iron bound for Japan. The unionists stated their actions were political – a protest at Japan’s brutal aggression in China and concern that Australia could become the next target of Japanese militarism. As Attorney-General and Minister for Industry, Menzies was the responsible minister.

Cabinet, deciding the ban must end, threatened the workers involved with the much-hated ‘dog-collar act’ – the Transport Workers’ Act 1929 that facilitated the hiring of strikebreakers on the wharves. Menzies tried to explain the government’s position by stressing that the issue was not whether the strikers were right or wrong in their views, but that only a duly elected government could determine policy. He was not helped by inconsistencies in government policy. It had earlier banned the export of iron ore to Japan on the grounds that Australia barely had enough for its own needs.

Attorney-General and Minister for Industry Robert Menzies earned the nickname 'pig-iron Bob' with his firm stand against the waterside workers who refused to load scrap iron heading for Japan in 1938. NAA: A432, 1938/1301, p.218

The dispute escalated, and by January 1939, some 7000 men were out of work. Menzies accepted an invitation to visit Port Kembla and confer with the union officials involved. He showed courage in coping with the organised mass demonstration that greeted him. In the end, the Port Kembla wharfies were forced to accept the government’s terms, and the ship was loaded with its cargo of pig-iron. The dispute cemented Menzies’ reputation with the labour movement as ultra-conservative, and for others that he was short-sighted on foreign policy issues.

Federal politics did not provide the high-flying Menzies with the easy path to the prime ministership that many expected. Some of the problems were of his own making. Despite possessing great personal charm, he could be arrogant and impatient with those he considered fools. In the hothouse atmosphere of Parliament House in Canberra, his haughtiness and cutting wit occasionally offended political opponents and Cabinet colleagues alike. As well, Lyons did not retire and allow Menzies to succeed to the office of Prime Minister.

By early 1939, the United Australia Party’s organisational leaders thought the government was ‘done for’. New blood was needed, but Menzies no longer seemed the logical successor. There was talk of drafting New South Wales Premier, BS (Bertram) Stevens, into the federal Cabinet and even of luring former Prime Minister Stanley Bruce back from his position as Australian High Commissioner in London. What brought matters to a head, however, was not the leadership issue, but a broken election promise.

At the 1937 federal election, the United Australia Party had promised to introduce a system of national insurance that would provide medical cover and pensions for working people. The scheme was to be funded by contributions from government, employers and employees. Menzies, who had helped draft the policy, was an enthusiastic supporter of the scheme. For him, it constituted good social policy and, once adequate superannuation funds had been accumulated, promised to relieve taxpayers of what was likely to become an intolerable burden in the future.

Unfortunately, the United Australia Party’s coalition partners were not nearly so keen about the proposal. Although a National Insurance Bill was passed, Country Party ministers continued to resist its implementation, arguing that the money was needed elsewhere, particularly to provide for ‘adequate defence’. After a series of stormy meetings, Cabinet succumbed to Country Party threats and decided to repeal the pension provisions of the Bill. Menzies immediately resigned from the ministry.

Although some within the party questioned Menzies’ decision, he was widely supported by the party rank and file and by the press. Menzies was thus a backbencher when less than 1 month later, on 7 April 1939, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons suddenly died.

Page government 7–20 April 1939

Because Menzies had resigned, the United Australia Party did not have a deputy leader at the time of Lyons’ death. Governor-General Lord Gowrie took the advice of Menzies’ successor as Attorney-General, William Hughes, and the deputy Prime Minister and Country Party leader, Earle Page, to commission Page to form a government. Page accepted on the understanding he would resign as soon as his senior coalition partners, the UAP, had chosen a leader. However, Page stipulated that if the UAP chose Menzies, he would not serve in the Cabinet.

In the lead-up to the party room meeting on 18 April 1939, 3 names emerged as likely contenders for leadership of the United Australia Party: William Hughes, Stanley Bruce and Robert Menzies. That 2 former prime ministers (one in his late 70s, the other not even a member of federal parliament) would be given serious consideration was an indication of Menzies’ low standing within some sections of the UAP. In the end, Bruce chose not to stand. On the day of the ballot, 4 candidates were nominated for the position of leader: Menzies, Hughes, Richard Casey and Tom White. Menzies won by 4 votes. His closest challenger was William Hughes.

Page was due to meet with the Governor-General and tender his resignation on the afternoon of 20 April 1939. That morning in the House of Representatives, Page launched one of the most extraordinary personal attacks ever seen in the Australian parliament. The years of political hostility and personal bitterness between the country doctor and the big-city barrister boiled over. Page said the Country Party could not serve in a coalition government headed by Menzies. He claimed Menzies had been disloyal to Lyons, had contributed to his death and was unfit to be Prime Minister. Furthermore, with war threatening, he claimed that Menzies was particularly unsuited to leading the nation. Page implied that Menzies was a shirker and a coward, asserting that in the First World War, he had resigned his commission to avoid overseas service. Such a person, Page claimed, would ‘not be able to get the maximum effort out of the people in the event of war’. The speech was greeted with cries of ‘shame’ from both UAP and Labor benches. Menzies’ dignified reply was listened to in silence.

On 26 April 1939, Menzies was sworn in as Prime Minister of a new United Australia Party government.

Sources

- Martin, Allen, Robert Menzies – A Life, Vol. 1, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1993.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Personal papers of Menzies as Attorney-General, 1934–38, NAA: CP450/7