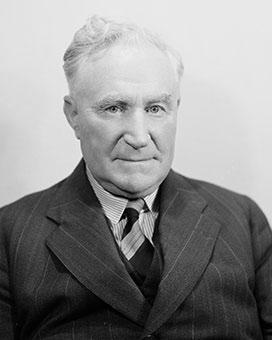

Pattie Menzies and Robert Menzies at their farewell in 1966, with John McEwen (left) and Harold Holt (right). NAA: M2576, 46, p.34

Pattie Menzies served the longest term as prime ministerial spouse, from 1939 to 1941 and from 1949 to 1966. She was a widely respected public figure, and was made Dame Grand Cross of the British Empire in 1954.

Pattie Maie Leckie came from a political family. Her father, John Leckie, was a Deakinite Liberal who was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly seat of Benambra in 1913 when she was 14 years old. He won the seat of Indi in the federal parliament in 1917 for the new Nationalist Party. Pattie often accompanied her father on tours of his electorate, until he was defeated in the 1919 federal election. In 1935, John Leckie became a United Australia Party Senator for Victoria. He served 2 terms in the Senate, and in 1941 was Minister for Aircraft Production in Robert Menzies’ wartime Cabinet.

Pattie Leckie first saw Robert Menzies when she was at school. It was not until 1919 that they were formally introduced and Menzies became a regular visitor at the Leckie home. The couple were married on 27 September 1920, at the Presbyterian Church in Kew. Their first home was a rented apartment in Kew. A series of other rented homes followed before they purchased the house in Howard Street, Kew, that was their family home for the next 25 years.

In 1929, the Menzies bought ‘Illira’, a modest house in the Macedon Ranges, north-west of Melbourne. ‘Illira’ was the family’s holiday retreat until it was destroyed by fire in November 1941, 3 months after Menzies lost the prime ministership to Arthur Fadden.

Mrs Menzies was a strong support in Menzies’ political career from the first. He was reluctant when invited to stand as United Australia Party candidate for the House of Representatives seat of Kooyong in 1934. Mrs Menzies convinced him to change his mind, arguing he could best serve the nation in Federal Parliament.

In 1935, the Menzies made the first of their many overseas trips, as part of the official Australian delegation to King George V’s silver jubilee celebrations in London. They were away from Australia for nearly 8 months. A highlight of the trip for both of them was meeting the British Royal family – the King’s granddaughter, Princess Elizabeth, was the same age as their own daughter Heather. At a dinner at Buckingham Palace, Queen Mary asked Mrs Menzies what had impressed her most during her visit. She replied: ‘You, your Majesty’.

Once their 3 children were in boarding school, Mrs Menzies began to spend more time in Canberra. When Earle Page made his bitter personal attack on Menzies in April 1939, she was in the public gallery of Parliament House. She walked out during the speech and never acknowledged Page again.

At The Lodge 1939–41

When Menzies became Prime Minister in 1939, the family moved into The Lodge in Canberra. Mrs Menzies undertook a thorough makeover of the residence. First, the makeshift children’s bedrooms on the front balcony, built for the large Lyons family, were removed. Worn carpets and furnishings were replaced and kerosene heaters installed. The kitchen also needed an overhaul and this was started.

One of Mrs Menzies’ duties during the Menzies’ next lengthy visit to London was to consult with the Duchess of Kent on her preferences for a redecoration of Government House in Canberra because the Duke of Kent was proposed as Governor-General when Lord Gowrie retired. On her return to Canberra, Mrs Menzies obtained the services of Myer consultant Dolly Guy Smith to direct the work at Government House. Mrs Menzies also had Guy Smith take charge of a redecoration of The Lodge, changing its 1920s ‘Ideal Home’ look to a more modern one with wall-to-wall carpets, pastel curtains and soft chintzes.

Mrs Menzies enjoyed life at The Lodge in Menzies’ first period in office. The Prime Minister came home for lunch, and after lunch and in the evenings the couple relaxed by playing snooker in The Lodge’s well appointed billiards room. She would usually go to Parliament House to listen to Prime Minister’s question time, and took a keen interest in political matters. She was a good judge of character, with a ‘nose’ for honesty and deception. She warned Menzies, when he was planning to leave for London in January 1941 that, if he went, internal party intrigue would cost him the prime ministership. She was proved correct. Although she always rejected suggestions that she exercised any political influence over the Prime Minister, Mrs Menzies was his closest political confidante.

When Menzies resigned in August 1941, Mrs Menzies was unhappy to leave The Lodge, since her redecoration was only recently completed. The move back to Melbourne was a reluctant one, but the role of political wife during the war years was busy there too. From 1941 to 1949, Mrs Menzies was a member of the board of management of the Women’s Hospital. She also followed Pattie Deakin’s footsteps and became involved in the Free Kindergarten movement. She served as president of some Women’s Hospital Auxiliaries in suburban Melbourne and nearby country towns.

In undertaking this charity work, Mrs Menzies lost her fear of public speaking. She discovered she could speak animatedly and at length about her own experiences, and hold the attention of her audience. She began to make notes of interesting events and file them for future needs.

At The Lodge 1949–66

In December 1949, Menzies again became Prime Minister following the Liberal Party’s success in the federal election. With some prescience, the couple sold their Melbourne house, and The Lodge became their family home for the next 16 years.

Mrs Menzies immediately set up further renovation and improvement at The Lodge, this time focusing on the kitchen. She often cooked for the family, and also for the Prime Minister’s Sunday night dinners for colleagues. A new Aga stove was installed, and the kitchen extended. A postwar shortage of domestic workers meant that Mrs Menzies was forced to choose between a cook and a housekeeper, but she often did the housework herself. On one occasion, an official calling at The Lodge was astonished to encounter the Prime Minister’s wife scrubbing the floor. John Bunting commented Mrs Menzies ‘had a domestic punch to match the political and departmental staff who often looked at her with a wary eye’.

Informality characterised the Menzies’ style of entertaining. A tennis match followed by a Sunday dinner would include parliamentary, party or departmental colleagues. In the Lodge’s small dining room, guests appreciated the intimacy, the simple food and the lively conversation. Even on more formal occasions, Mrs Menzies could often be found helping out in the kitchen, if not cooking the meal herself. She became adept at disappearing up the back staircase to her bedroom, only to reappear soon after at the front staircase dressed to receive the guests.

During Menzies’ second term as Prime Minister, Mrs Menzies accompanied him on almost all domestic and overseas tours. She undertook many public engagements, her friendly manner and quiet sense of humour winning her many admirers. One observer referred to her as ‘Menzies’ secret weapon’. She found it necessary to devote part of each day to answering a voluminous correspondence, using The Lodge’s snooker table as her makeshift desk. With no secretarial help, she personally answered every letter. She was closely involved in the development of Canberra, with the minister in charge, Doug Anthony, revealing he ‘kept a line to Dame Pattie and her ideas as much as the Prime Minister’.

In recognition of Mrs Menzies’ public work, Queen Elizabeth conferred on her the honour, Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, during the 1954 Royal visit.

When Menzies resigned as Prime Minister in 1966, the couple retired to a new home in Melbourne, bought for them by wealthy friends and supporters in recognition of their contribution to the nation. They spent part of each year in the United Kingdom, staying at Walmer Castle in Kent, which Menzies was entitled to use as Warden of the Cinque Ports.

After Menzies’ death in 1978, Dame Pattie continued to support a range of organisations and causes. She was regularly called on for Liberal Party events, including election campaigns and the party’s 50th anniversary in 1994.

In 1992, Dame Pattie moved back to Canberra to live with her daughter. She died in Canberra on 30 August 1995.

Sources

- Bunting, John, ‘A life of public grace’ [obituary], Australian, 31 August 1995.

- Langmore, Diane, Prime Ministers’ Wives: The Public and Private Lives of Ten Australian Women, McPhee Gribble, Ringwood, Victoria, 1992.

- Menzies, Robert, The Measure of the Years: Prime Minister of Australia, 1939–41 and 1949–66, Cassell, London, 1970.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Prime Minister’s Lodge Staff, Part 1, 1926–50, NAA: A461/704/1/12

- Prime Minister’s Lodge — repairs, maintenance, replacements and additions, 1952–60, NAA: A463, 611958/51, Parts 1 & 2