After voters removed him from office in 1929, Stanley Melbourne Bruce regained his seat in the House of Representatives in 1931. He served as a minister in the government of Joseph Lyons, first as Assistant Treasurer and then as Special Minister in London. In 1932, he led the Australian delegation to the Ottawa Conference where new Empire trade agreements were negotiated. In 1933, he resigned his seat to become Australia’s High Commissioner in London. He held this post until 1945, building a reputation as a sound and steady statesman in international affairs, and serving on the British War Cabinet.

High Commissioner

Bruce was Australia’s High Commissioner to Britain for 12 years from 1933 to 1945. He served both United Australia Party and Labor governments during this period of international tension. This critical period saw the rise of fascism and Nazism in Europe and Japanese aggression in Asia, mounting international tensions leading to World War II, and the re-establishment of peace. He was respected by the British ‘Establishment’, and was widely consulted by leading Conservative Party figures.

In the New Year Honours list of 1947, Bruce was raised to the peerage as the Viscount Bruce of Melbourne. He was the only Australian prime minister to become a British peer.

League of Nations

Bruce had been appointed by William Hughes as Australian delegate to the first General Assembly of the League of Nations in 1921. In the 1930s, he had a distinguished career at the League. As High Commissioner to Britain, he was a member of the Australian delegation to the General Assembly from 1932.

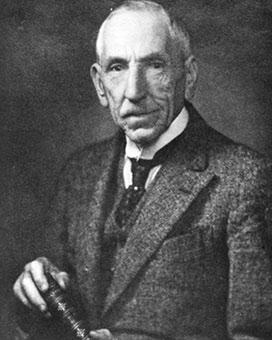

Stanley Bruce chairing a League of Nations conference in Montreux, Switzerland, in 1936. NAA: M112, 1, p. 17

Bruce served as President of the League Council in 1936 during the Ethiopian crisis. During this year, he presided over the conference in June and July that resulted in the Convention of Montreux, an international agreement that successfully and permanently regulated passage of warships through the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits. A memento of this achievement – a cigarette case presented to him by Turkish leader Kemal Ataturk – was a favourite item, well-used over the next 30 years.

When the League entered its final years at the end of the 1930s, Bruce remained one of the most stoic and determined of international statesmen. In 1939, Bruce chaired the League’s special committee on the development of international cooperation in economic affairs.

Commemorative gavel presented to Stanley Bruce after the Food and Agriculture Organisation Preparatory Commission. NAA: M4254, 33

The Bruce Report, produced in 1939 and overtaken by the outbreak of war, anticipated the role later taken by the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations after 1945. Bruce’s commitment to systematic agricultural marketing as a key to sound economic development bore fruit in his work on international nutrition with Frank McDougall.

From 1946 to 1951, he chaired the Preparatory Commission and then the World Food Council of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations.

In 1951, Bruce became the foundation chancellor of the Australian National University, serving until 1961. Of all his honours, however, Bruce’s fondest achievements were his Cambridge Rowing Blue, his fellowship of the Royal Society, awarded in 1944, and his captaincy of the home of golf, the ‘Royal and Ancient’ St Andrews Club in Scotland.

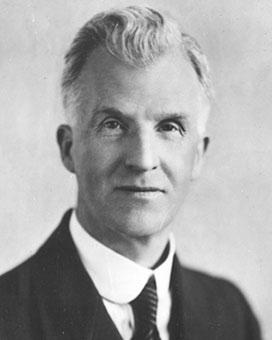

Stanley Bruce, first chancellor of the Australian National University, with Earle Page, first chancellor of the University of New England. NAA: A1200, L25029

Death

Bruce died where he had lived for almost half of his life – in London. He ordered that he be cremated, and provided in his Will that his ashes be returned to his native land and scattered over the national capital. Canberra, the city he had helped create, remains a monument to this Prime Minister.

The last Will of the Right Honourable Stanley Melbourne Viscount Bruce was signed by him in London on 4 August 1963, 4 years before his death. Ethel Bruce died in March 1967, a few months before Bruce’s death on 25 August 1967. Without heirs, the private beneficiaries of his substantial estate were his brother’s wife, her children and grandchildren, and two staff members, Emily Tindall and Nora Roberts.

Bequests were made to his old school, Melbourne Grammar, and to Trinity Hall Cambridge. He also provided for the establishment of a fund to promote ‘research relating to the application of science to industry in Australia’ at the Australian National University. He left bequests to Lincoln’s Inn, the Royal Society, and Trinity Hall for the purchase of ‘a piece of plate’ in memory of his association with each. England’s Lucifer Golfing Society was also provided the handsome sum of 1000 pounds to establish an annual Overseas Empire Golfers competition.

The final clause of the Will states:

I desire that my body may be cremated and that my ashes shall unless there be some law to the contrary be scattered over Canberra Australian Capital Territory ...

This rather unusual request was carried out and the remains of this soldier and statesman returned to his native land – not to Melbourne, where he was born, but to the capital of the nation. His ashes were scattered over the heart of the city, across the new Lake Burley Griffin planned by Walter and Marion Griffin in 1911, but not created until 50 years later when the Menzies government implemented the plan.

Bruce also willed a gift to the people of Australia – the collection most important to him, containing 100s of items ranging from gifts received as Prime Minister and in other official capacities to memorabilia of his sporting prowess.

Sources

- Edwards, Cecil, Bruce of Melbourne: A Man of Two Worlds, Heinemann, London, 1965.

- Hudson, WJ, Australia and the League of Nations, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1980.

- Radi, Heather, ‘Stanley Melbourne Bruce’, New Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oxford, (forthcoming) 2004.

- Stirling, Alfred, Lord Bruce: The London Years, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1970.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Photograph album of the Montreux Conference, 1936, NAA: M112, 1