Cabinet

Stanley Melbourne Bruce was 39 years old when he was sworn in as prime minister on 9 February 1923, Australia’s second youngest prime minister, after Chris Watson. With the new Country Party unwilling to serve under William Hughes, Bruce established a coalition with Country Party leader Earle Page as the deputy prime minister. While generous in the allocation of portfolios to coalition ministers, Bruce was a firm and focused leader. He saw his role as head of government as requiring strong leadership, firm planning, and sound and efficient economic management.

Bruce's ‘National Objectives’ speech, delivered on 23 September 1924, was printed for distribution. NAA: A1491, 1, p.1

In his first speech to the parliament in March 1923, the new Prime Minister laid out a policy map for Australia in the 1920s, including:

- economic development through ‘men, markets, and money’

- Australian participation in shaping the British empire's foreign policy

- more effective Commonwealth–State financial arrangements

- the establishment of the national capital

- increasing federal powers in industrial relations.

One of Bruce’s first actions was to implement the reform of Cabinet meetings he had earlier tried to make under a recalcitrant Hughes. His new system required ministers to prepare papers on agenda topics and to consult with him before Cabinet meetings. He reformed meeting procedures, following agenda items in turn and appointing an ‘honorary minister’ to take minutes. In 1925, this position became Cabinet Secretary and, from 1928, the Cabinet Secretary and the Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department prepared the Cabinet agenda in consultation.

Economic development

Among the key topics Bruce covered in his first speech to parliament as prime minister was Empire trade – the ‘men, money and markets’ theme. To Bruce, strict business principles provided a sound and rational approach to government, cutting through party interest, political deal-making and inefficient practices. Bruce took every opportunity to press his arguments for an ‘Empire agriculture’ system that would ensure Australian-grown produce took pride of place on British plates, while Australia found employment for British investment and for British workers, both men and women. He saw his visit to Britain for the 1923 Imperial Conference as an opportunity to address not only government officials at Whitehall, but his familiar circle of finance and trade – and even the ‘lions’ den’ itself, the British National Farmers Union.

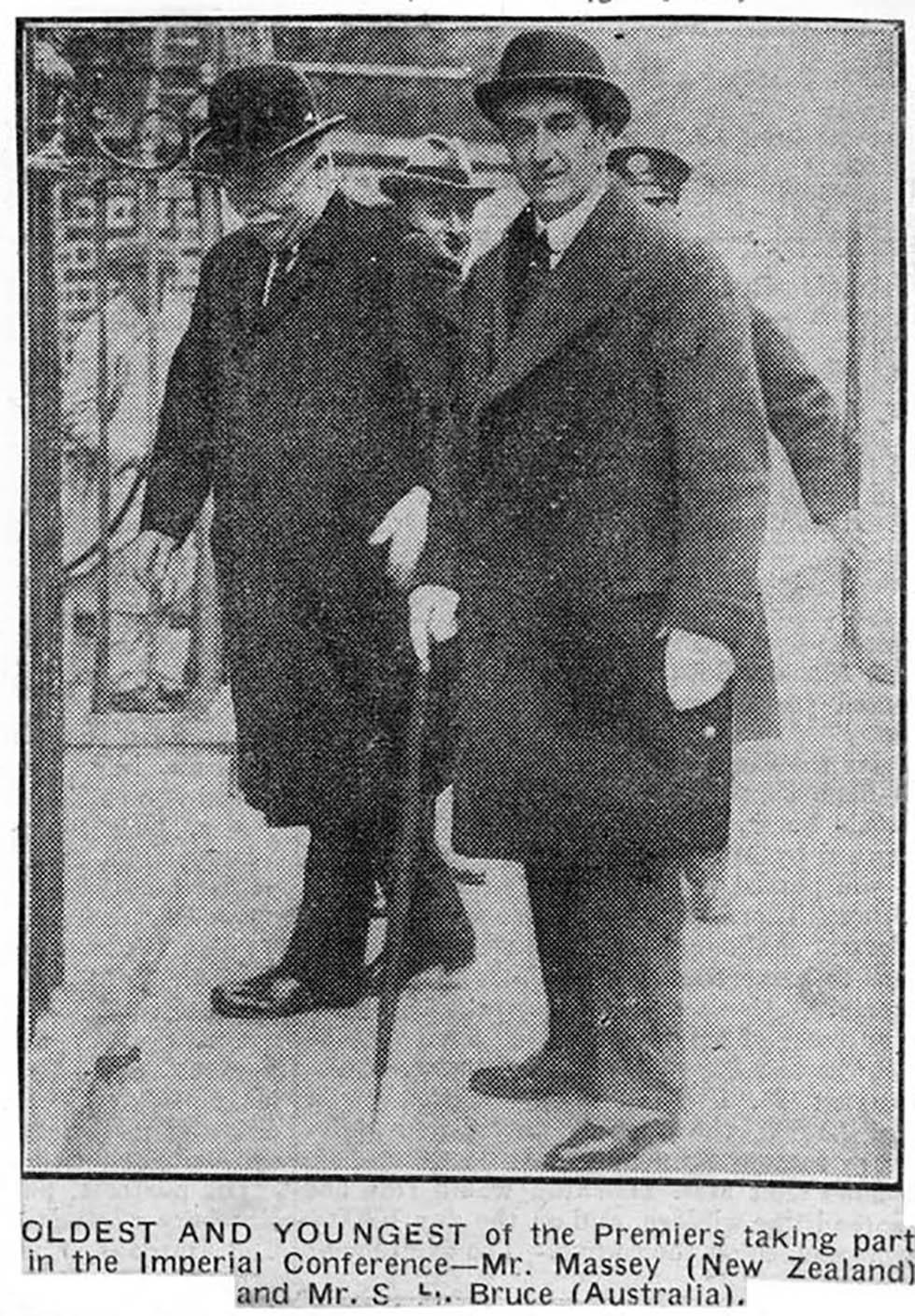

The Bruces’ 4-month visit was well-received in Britain, with ample and mostly appreciative press coverage. The youngest of the British dominion prime ministers always seemed to be at the centre of things. Equally, the new Prime Minister’s wife took up her public role with aplomb. She participated in Royal banquets, parliamentary occasions and other official events. She even became the embodiment of the Australian appeal for women domestic workers – she was an assurance to potential recruits that homes of elegance and civility existed even in the antipodes.

Stanley Bruce, the youngest prime minister attending the Imperial Conference, October 1923. NAA: A1486, 1, p.13

At home the following year, Bruce continued to explain and promote the Empire trade policy, a topic of inexhaustible interest to him. His government implemented British immigration programs, focusing on agricultural and domestic workers, and on child migration.

Foreign policy

In his first speech to the parliament, the new Prime Minister argued for an Australian defence policy in cooperation with Britain. In London at the 1923 Imperial Conference, he was equally clear that this meant Australia should participate in shaping the Empire’s foreign policy. Bruce recalled that, when he questioned the British Foreign Affairs Secretary on policy matters:

Curzon, who was a somewhat superior person, was obviously annoyed and we had a fairly crisp exchange. However, two or three days later he made a further statement in which he gave some indications of the views of the Government. I left no doubts that we expected to be fully informed on foreign policy, and had every intention of expressing our views.

To implement this, Bruce secured the agreement of the British Prime Minister (Stanley Baldwin, and then Ramsay Macdonald) to establish an Australian liaison officer in the British Foreign Office. Bruce appointed Richard Casey to the post, which was even more usefully located in the British Cabinet Office. Bruce made full use of Casey, who remained the Australian liaison officer until 1931. When the post was abolished in Scullin government cutbacks, ‘without saying anything to anyone’, Bruce, then in London, established Frederick Shedden in the British Cabinet Office to fill the role. When the position was restored in 1932, Bruce was influential in the appointment of the next 2 Australian liaison officers, Keith Officer and then Alfred Stirling.

The 1926 Imperial Conference continued the work of the 1923 Conference in responding to the demands of South Africa and Canada for a clearly defined status of the British dominions in their relations to Britain. To Bruce, this was of less importance for Australia than the sound economic ties he sought. He remained as opposed to the ‘codification’ of this relationship as his Attorney-General, John Latham – an opposition that ensured Australia delayed ratification of Britain’s 1931 Statute of Westminster for over 10 years.

Commonwealth–State financial arrangements

As announced in his March 1923 speech, Bruce held Commonwealth–State talks in June 1923. The Commonwealth proposal to replace per capita distribution with annual payments to the states was high on the agenda. The government also introduced tied grants to the states under Section 96 of the Constitution, such as the Commonwealth Aid for Roads program, the foundation of Australia’s highway system.

The adjustment of federal financial relations sought by the Bruce–Page coalition required an amendment to the Australian Constitution which, in turn, meant a national referendum. Held on 17 November 1928, the successful referendum was implemented with the insertion of Section 105A into the Constitution. The new section provided for financial agreements between the Commonwealth and the states relating to the public debts of the states, and set up a Loan Council.

However, by this time, the slump which led to economic depression had begun. The following year, the more pressing problems of serious industrial conflict dominated federal politics.

National capital

The Bruce–Page government also completed the ‘unfinished business’ of establishing the national capital, which was suspended soon after its foundation in 1913 while Australia was at war from 1914 to 1918. Building the city and transferring the seat of government from Melbourne to Canberra in 1927 was a major task of the Bruce–Page government.

Opening of Federal Parliament in Canberra, May 1927. NAA: A6180, 20/5/74/42

Industrial relations

Industrial relations was the third area of the ‘unfinished business’ of the Constitution addressed by the Bruce–Page government. Commonwealth and state responsibilities in conciliation and arbitration had unseated and unsettled governments since Federation.

In the Engineers Case, a landmark judgment in 1920, the High Court had ruled that state governments must obey the rulings of the Commonwealth Arbitration Court. This was the argument put by the barrister representing the Engineers’ Union, Robert Menzies. To the union movement, this made pursuing uniform wage and working standards more effective. The influence of John Latham, Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the Bruce–Page government at this time, brought the government into conflict with the Labor Party and the trade unions.

The Bruce–Page government met industrial action with severe penalties, such as the 1926 amendment to the Crimes Act and the 1928 Transport Workers Act. This heightened the tensions of industrial conflict. Strikes of sugar mill workers in 1927, waterside workers in 1928, then of transport workers, timber industry workers and coal miners erupted in riots and lockouts in New South Wales in 1929. Bruce responded with a Maritime Industries Bill that was designed to do away with the Conciliation and Arbitration Court and return arbitration powers to the states.

On 10 September 1929, William Hughes and 5 other Nationalist members joined Labor in voting against the Bill. The ballot was lost 34 votes to 35 when Littleton Groom, the Speaker, abstained, bringing down the Bruce–Page government.

Sources

- Brett, Judith, 'Stanley Melbourne Bruce' in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland, Sydney, 2000, pp. 126–38.

- Cumpston, IM, Lord Bruce of Melbourne, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1989.

- Edwards, Cecil, Bruce of Melbourne: A Man of Two Worlds, Heinemann, London, 1965.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Volume of press cuttings ... Imperial Conferences, 1923–24, NAA: A1486, 1

- Correspondence between SM Bruce and RG Casey, 1925, NAA: A1420, 2

- Big Brother Scheme, 1924–28, NAA: A436, 1945/5/2217