After he resigned as Prime Minister in 1923, Hughes was a backbencher in the government of Prime Minister Stanley Bruce. Hughes precipitated the fall of the Bruce government in 1929 and was expelled from the Nationalist Party. When Joseph Lyons defected from James Scullin’s Labor government in 1931, Hughes joined him in forming a new United Australia Party.

After Lyons became Prime Minister in 1932, Hughes was at various times Minister for Repatriation, Minister for Health, Minister for External Affairs and Minister for Territories. He was also Attorney-General in Robert Menzies’ first government (1939–41), and held the Industry and Navy portfolios.

Hughes led the United Australia Party from 1941 to 1944, but was expelled for continuing to serve in the Labor government’s Advisory War Council against a party directive. A member of Robert Menzies’ Liberal Party from 1945 and of his government from 1949, Hughes remained a backbencher until his death in 1952 at the age of 90.

Government backbencher 1923–29

When Hughes resigned as Prime Minister, he remained a backbencher in the Coalition government led by Stanley Bruce and Country Party leader Earle Page. In the lead-up to the 1925 federal election, Hughes’ eldest daughter forced him to make better financial provision for the 5 children of his first family. After she threatened to reveal their story to the press, a secret agreement drawn up by Hughes’ solicitor ensured the matter remained out of the public eye.

After the 1925 election, Hughes became an increasingly sharp critic of the government, particularly of Bruce’s industrial relations policy. Bruce was convinced that increasing wages would stall the economic growth of the early 1920s and responded to industrial action with heavy penalties. He was also determined to return the conciliation and arbitration power to the States. In 1929 he introduced a Maritime Industries Bill designed to dismantle the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Court.

Hughes organised a small group of like-minded Nationalists and, on 10 September 1929, the group voted with the Labor Opposition against the Bill. The ballot was lost 34 votes to 35 when Littleton Groom, the Speaker, abstained. With this demonstration of the loss of majority support in the House of Representatives, Bruce was forced to an election in October 1929 and a Labor government was returned. Hughes was promptly expelled from the Nationalist Party he had founded in 1916.

Bruce lost his seat at the 1929 election, but Hughes was comfortably returned for North Sydney as an ‘Independent Nationalist’. In that role he provided some support for the government of James Scullin. Hughes then joined forces with Labor dissident Joseph Lyons and aligned with the Nationalist Opposition. By the 1931 election, the Labor Party had split and Hughes contested his seat for the new United Australia Party formed by Lyons.

The Lyons government 1932–39

For the election of 1931, the Labor Party’s catastrophic three-way split led to a political realignment. This enabled Hughes to join the United Australia Party government led by Joseph Lyons.

In 1932, Lyons appointed Hughes to Australia’s delegation to the General Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva. Hughes held no ministerial portfolio until October 1934, when he became Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Health and Repatriation. In the Health portfolio he is chiefly remembered for a speech in February 1935 in which he argued that ‘Australia must ... populate or perish’.

Hughes’ return to the ministry was short-lived. When his 1934 book The Price of Peace was republished in October 1935 as Australia and the War Today it included a reference to sanctions as ‘either an empty gesture, or war’. Lyons withdrew Hughes’ portfolio the following month. Cabinet had moved to support the League of Nations policy of sanctions after Italy had invaded Abyssinia, and Hughes’ views contradicted government policy. But the suspension did not last long. In February 1936 Hughes returned to Cabinet as Minister for Health and Repatriation until 1937, when he became Minister for External Affairs.

In 1937, the Hughes’ only child, Helen, died in London, 2 days before her 22nd birthday. Her parents both doted on her, and neither was aware of the pregnancy that caused her death. The tragedy was public, and hundreds of people attended the Sydney funeral, including Prime Minister Joseph Lyons and Enid Lyons and the Hughes’ vast network of political associates, friend and foe.

Menzies and Fadden governments 1939–41

Joseph Lyons died in April 1939, and Hughes was narrowly defeated by Robert Menzies for the leadership of the United Australia Party. Once more he became deputy leader. He also served as Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the Menzies government from 1939 to 1941. With the outbreak of the Second World War, Hughes became a member of the War Cabinet.

When Menzies resigned the prime ministership in August 1941, Hughes became leader of the United Australia Party, and Attorney-General and Minister for the Navy in the government of Arthur Fadden.

In Opposition 1941–49

The Fadden government was defeated in parliament on 7 October and John Curtin formed a Labor government. Hughes became deputy Leader of the Opposition under Fadden. Despite hostility from Menzies and a group of dissatisfied followers, Hughes led the United Australia Party in the elections of August 1943.

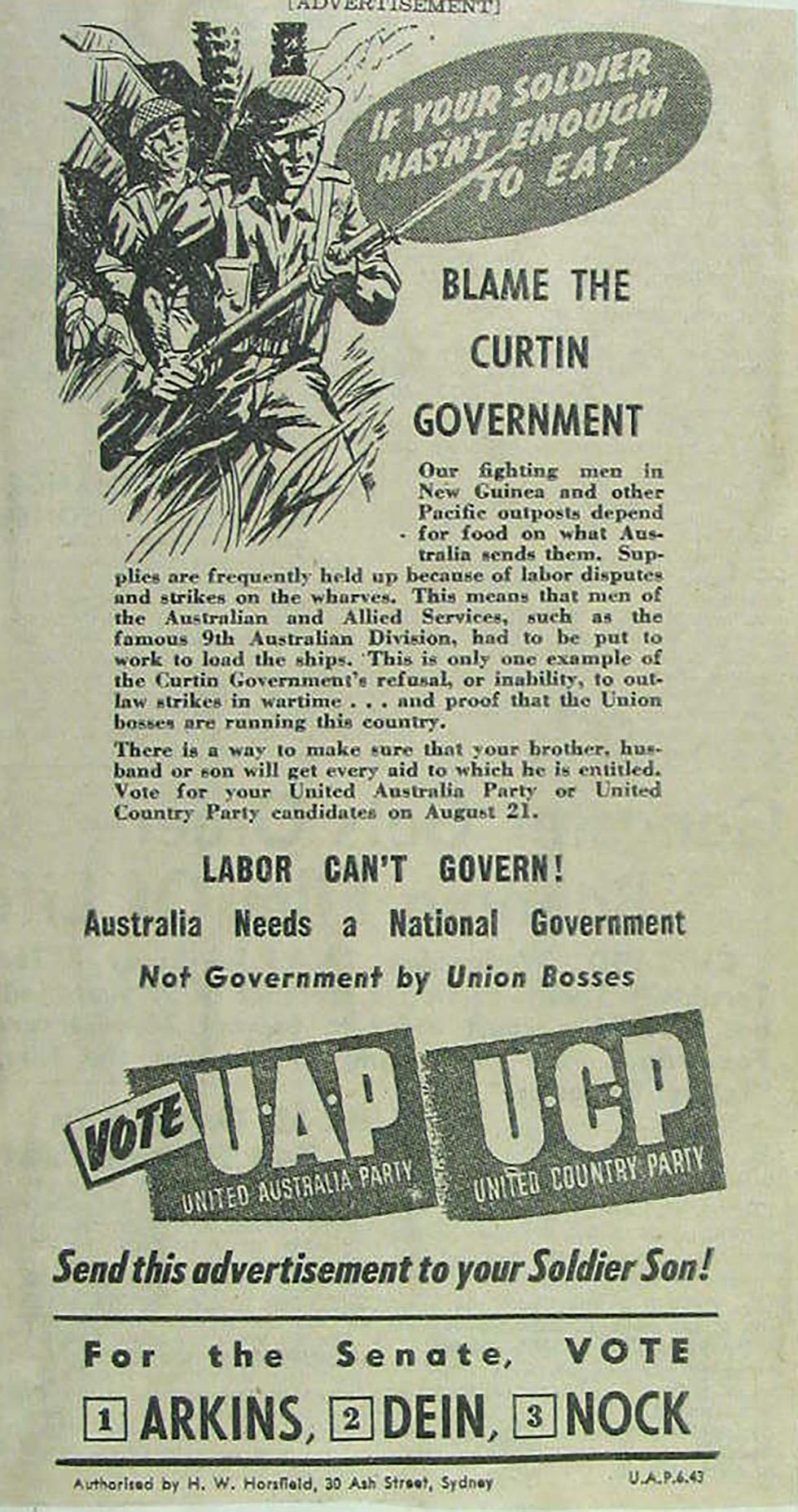

Opposition election advertising in the 1943 election campaign was declared in breach of National Security Regulations, affecting morale among the troops and on the home front. NAA: A5954, 598/4, p.25

The United Australia Party and Country Party election campaign advertisements declaring ‘if your soldier hasn’t enough to eat blame the Curtin government’ and ‘send this advertisement to your Soldier Son’ created a controversy, but failed to persuade voters.

The result was a landslide victory for Labor. Hughes immediately resigned as leader of the United Australia party and again became deputy to Menzies.

On 18 February 1944 the United Australia Party withdrew from the Advisory War Council, claiming the all-party council was increasingly futile and muted legitimate Opposition criticism of the government. Less than 2 months later, Hughes defied the party line and rejoined the council at the written request of Prime Minister John Curtin. As a result, Hughes was expelled from the United Australia Party, but remained on the War Council until the end of World War II. Hughes stayed in parliament as an Independent until September 1945, when he joined Robert Menzies’ new Liberal Party.

William Hughes defied his party to remain on the Advisory War Council in 1944 and was expelled. NAA: A5954, 2217/3, p.3

Menzies government 1949–52

At the age of 87, Hughes changed electorates for the fourth time and stood for the new electorate of Bradfield in 1949. This was a Sydney seat created in the expansion of the parliament that year. Hughes won the seat, and the Liberal Party won government. Hughes sat on the government back benches for his last three years in the House of Representatives.

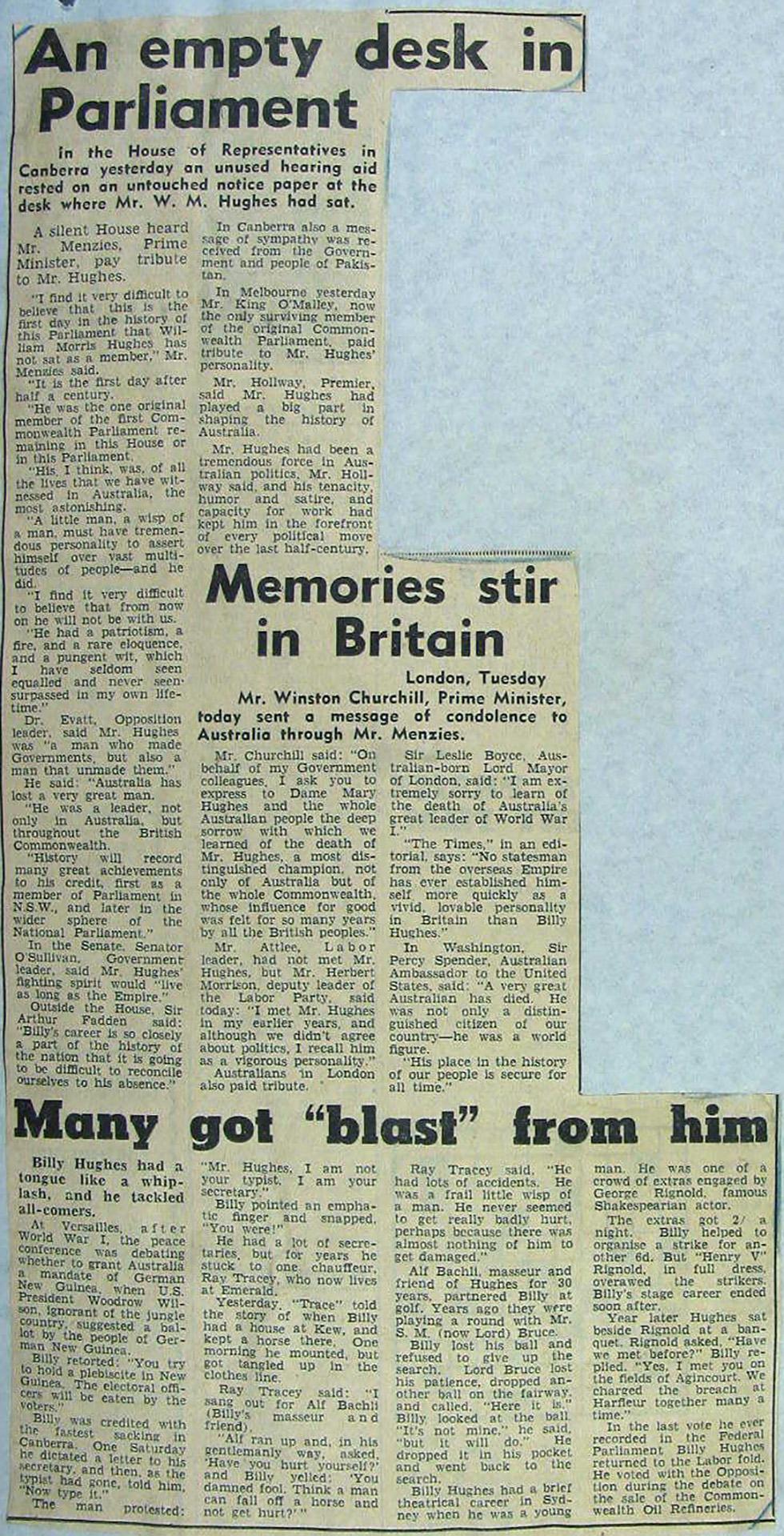

The death of William Hughes marked the end of the first 50 years of the Australian parliament. NAA: A5954, 2156/1, p.13

On 29 October 1952, Prime Minister Robert Menzies told the House of Representatives ‘I find it most difficult to realise that this is the first day in the history of the Federal Parliament in which William Morris Hughes has not sat as a member’. Hughes had died at his home the previous day.

Sources

- Hughes, Colin, Mr Prime Minister, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1976.

- Fitzhardinge, LF, The Little Digger 1914–1952, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1979.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Election campaign, July/August 1943, United Australia Party advertisement 5 August 1943, NAA: A5954, 598/4

- Expulsion of Mr Hughes from the United Australia Party, 1944, NAA: A5954, 2217/3

- Statements by the Leader of the United Australia Party, 1942–54 (includes W Kent Hughes), NAA: A5954, 2156/1

- Condolences – Rt Hon. Hughes, WM, 1952, NAA: A462, 860/2/56 Part 2