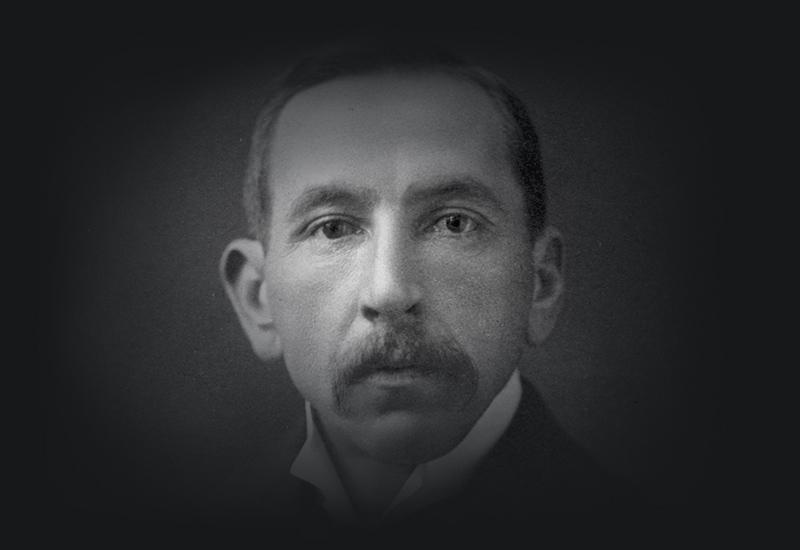

William Morris Hughes was Labor Prime Minister in 1915–16, then was expelled from the party over his support for conscription. He held two referendums on the issue, convinced that only compulsory reinforcements of troops overseas would win the war. After his expulsion, Hughes formed the Nationalist Party and remained Prime Minister until 1923.

In 1918-19, Hughes travelled to England and headed the Australian delegation at Versailles for the signing of the peace treaty in 1919. He was again in England in 1921 for an Imperial conference.

Hughes was popularly known as ‘the little Digger’ for his leadership of the nation throughout the war. But after the formation of the Country Party, Hughes was unable to retain support in the House of Representatives and resigned on 9 February 1923 in favour of Stanley Bruce.

Labor Prime Minister 1915–16

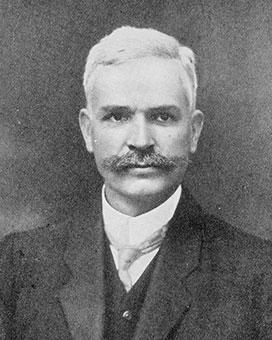

Hughes was sworn in as Prime Minister and Attorney-General by Governor-General Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson on 27 October 1915. Included in his Cabinet were George Pearce as Minister for Defence and King O’Malley as Minister for Home Affairs. Hughes immediately decided that he should go to London for direct consultations on the progress of the war.

Hughes’ absence meant the long-planned referendum for greater Commonwealth powers was postponed. For many on the left of the party, like Labor backbencher Frank Anstey, this was a betrayal. Critics saw it as evidence of the backsliding of Labor politicians once they had achieved office.

Leaving George Pearce as acting Prime Minister, William and Mary Hughes sailed from Sydney with their baby daughter on 26 January 1916. They travelled via New Zealand, where Hughes consulted Prime Minister William Massey, then to Canada for a meeting with Prime Minister Robert Borden. The Hughes reached England on 7 March, and spent the next three months in Britain and visiting Australian troops in the front line in France. Despite frequent ill health, Hughes made rousing speeches that were received enthusiastically.

2 contacts were of particular assistance to him. Andrew Fisher had put him in touch with journalist Keith Murdoch, and this enabled Hughes to circumvent Fisher by using Murdoch as his main London contact. He also found businessman William Robinson an invaluable means of furthering Australia’s interests. Hughes was appointed a British government representative at a 1916 Paris economic conference, where he met United States (US) Secretary of State, Robert Lansing.

In an audacious coup, Hughes circumvented British wartime controls on shipping by secretly purchasing fifteen cargo vessels on behalf of the Australian government. These ships were to convey Australia’s wheat and other commodities to British markets, and became the foundation of the Commonwealth Shipping Line.

One of the reasons for Hughes’ London visit had been to improve communication with Britain’s Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith on Australia’s concern about Japan’s activities in the Pacific. Despite Hughes’ opposition, Britain acceded to Japan’s occupation of former German territories so long as Japan did not fortify these islands.

Nationalist Prime Minister 1916–23

The Hughes arrived back in Australia on 31 July 1916, the country divided on the question of compulsory military service overseas. The conservative parties, the press and even most Protestant church-leaders had by then come out in support of conscription. Trade unions condemned the suggestion, and Labor activists like John Curtin and James Scullin in Victoria were organised in their opposition. The Catholic Church, particularly Archbishop Daniel Mannix, also opposed.

Hughes had seen Australian troops in the hospitals and camps of England and in the trenches in France, and believed passionately that urgent reinforcements were necessary. He called a referendum to obtain support for his proposal to introduce conscription. After a bitter and divisive campaign, his proposal was defeated at the poll on 28 October 1916. This would reinforce ongoing Catholic — Protestant sectarianism.

Hughes and other Labor members, like Chris Watson, who advocated conscription were then expelled from the Labor Party. Hughes also lost the position as union secretary for the Sydney wharf labourers he had held for 17 years.

At a meeting in the party room in Parliament House in Melbourne on 14 November, Hughes led his followers out of the Labor Caucus. They formed a ‘National Labor Party’, with sufficient numbers in the House of Representatives to retain government under Hughes. A new ministry consisting entirely of members of the breakaway group was sworn in the same day.

After lengthy negotiations, on 17 February 1917 a new Nationalist government was formed, consisting of 5 National Labor members and 6 former Liberal Party members. Among them were Joseph Cook and John Forrest.

Frank Tudor was elected Labor Party leader, and he led a fierce Opposition to the Hughes government. From then, Hughes was for the Labor Party a man who breached solidarity and abandoned principles for power.

In the Senate, the government’s followers were in the minority. Hughes attempted to force a resolution through the Senate requesting the British parliament to amend Australia’s Constitution so as to extend the life of the parliament. The ploy failed and the scheduled election went ahead. Hughes could no longer hold the working class seat of West Sydney, and stood instead for Bendigo. In any case, he had not lived in Sydney since 1901, and from his marriage in 1911, his family home was in Melbourne.

Despite the referendum defeat only 6 months previously, Hughes easily won the general election on 5 May 1917. During the election campaign, when questioned about conscription he had pledged that if ‘national safety demands it, the question will again be referred to the people’.

The most difficult year of the war was 1917. Industrial unrest resulted in the most serious strike in New South Wales since the 1890s, and it was put down with severity by the state government. By November, the worsening reinforcement situation of the Australian Imperial Force in France and a sustained drop in recruitment persuaded the government that conscription was essential to providing reinforcements and maintaining Australian honour.

Resignation and reinstatement

In view of his promise during the election campaign, Hughes was compelled to call another referendum. After an even more bitter campaign than the year before, with Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix a leading anti-conscriptionist, the referendum was held on 11 December 1917. Again, the government’s proposals were defeated.

Hughes had pledged during the referendum campaign that his government would not attempt to carry on without the powers to conscript. After being refused those powers, his position was precarious.

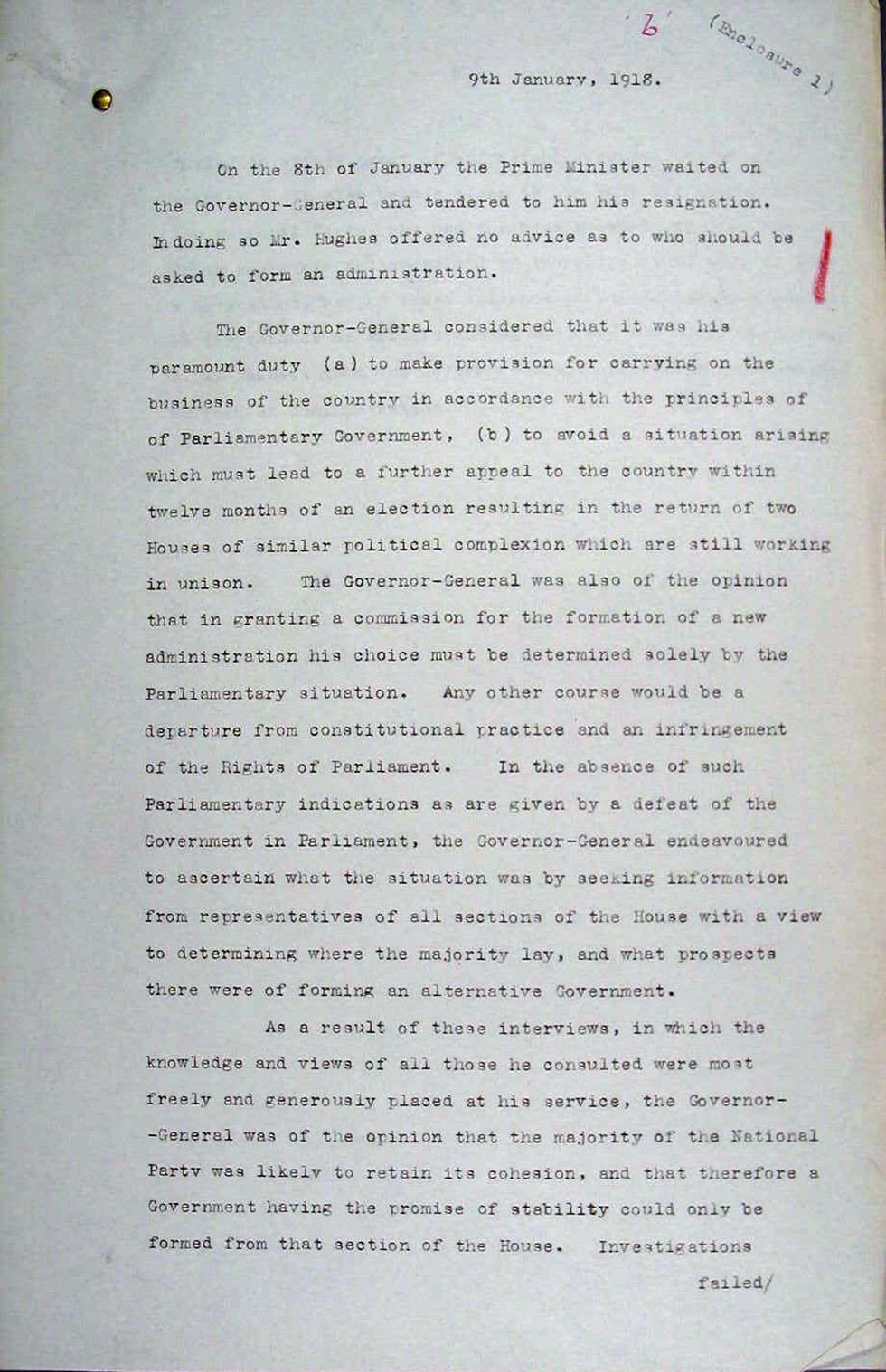

The record of the Governor-General's response after William Hughes resigned as Prime Minister on 9 January 1918. NAA: A11047, Constitutional 4, p.12

Hughes first secured a vote of his party expressing ‘continued confidence’ in him as leader. He then resigned without recommending a successor. Governor-General Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson consulted both the Labor Opposition and the Nationalist Party. Labor was in a decided minority in both Houses, and Nationalist Party members refused to support or form a coalition with the Opposition. Left with no alternative, the following day the Governor-General recommissioned Hughes, who had thus both fulfilled his pledge and kept his office.

The Governor-General had little confidence in Hughes’ capacity as an administrator, finding him unwilling to delegate or to consult his colleagues. Munro-Ferguson likened Hughes to ‘a jackdaw who pounces on everything and secretes it in his own nest’. Although Hughes had a remarkable memory and the ability to grasp and master subjects quickly, he was often irritable and impatient. His deafness meant that he used an ‘accousticon’ or hearing machine, but when he wished not to hear, would just turn this off.

Early in 1918, the British government of David Lloyd-George decided to hold a meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet and Imperial War Conference. Leaving WA Watt as acting Prime Minister, William and Mary Hughes, with their 2-year-old daughter Helen and adviser Robert Garran, left Sydney on 26 April 1918. Travelling via Canada and the United States of America, they visited Washington for a meeting with US President Woodrow Wilson. Hughes firmly put his case that Australia should retain the former German territory of New Guinea at the end of the war, but Wilson remained unconvinced.

In London, Hughes attended the Cabinet and Conference meetings from June to August. He dealt with trade issues, and with administrative and command matters involving the Australian armed forces. But his primary aim in attending the Imperial War Conference and Imperial War Cabinet meetings was to ensure Australia’s independent representation in the peace process.

In July, Hughes urged a change in imperial administrative arrangements to allow direct government-to-government communications between the United Kingdom and the dominions. Hughes opposed the adoption of US President Woodrow Wilson’s 14-Point Plan because it appeared to allow international intervention in colonial and national issues.

Early in October 1918 it was clear the end of the war was close. Hughes resolved to remain in Europe to represent Australian interests in the ensuing peace negotiations.

Versailles 1919

Hughes had a major influence on Australia’s external relations in the first half of the 20th century. His conduct of matters while in Paris attending the Peace Conference from January to June 1919 with Navy Minister Joseph Cook was the peak of this achievement. His arguments pushed the case for Australia and the other British dominions to have independent membership of the League of Nations, despite the reluctance of the US.

A leading figure in the Reparations Commission, Hughes argued that Germany must pay for the costs of the war and pressed for Australia to be compensated for its war-related expenditure. His hard line and energetic defence of Australia’s interests in the postwar alignment of former dependent territories became legendary.

On the issue of former German New Guinea, Hughes fought for Australia to gain control of the territory, in the face of President Wilson’s strong opposition. When asked by the American leader if he were prepared to defy the opinion of the whole civilised world, Hughes replied ‘That’s about the size of it Mr President’. Reminded that he spoke for only 5 million Australians, he responded passionately, ‘I represent sixty thousand dead’. Hughes achieved his aim. A special class of mandate was created, allowing the territory to be administered as an integral portion of the mandating country.

The third point Hughes pursued in Paris was to block the attempt of the Japanese delegation to insert in the covenant of the League of Nations a clause guaranteeing ‘equality of nations and equal treatment of their nationals’. Seeing this as a threat to the White Australia policy, Hughes successfully lobbied the commission, and the vote was lost.

A French journalist described Hughes at Versailles in the following words:

frail, narrow-shouldered, stooped, with the long, metallic face, seamed with lines, of a Breton peasant, at first he sits doubled up like a spider and lets others talk ... but suddenly he straightens out, darts forward his thin arms and the double trident of stretched out fingers and cuts through the flabbiness of the discussion with a word.

On 28 June 1919, Hughes and Cook lined up with the representatives of the nations in the palace’s Hall of Mirrors and signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of Australia. At the end of the conference, Australia was a full member of the League of Nations and the British dominions had achieved a new international status.

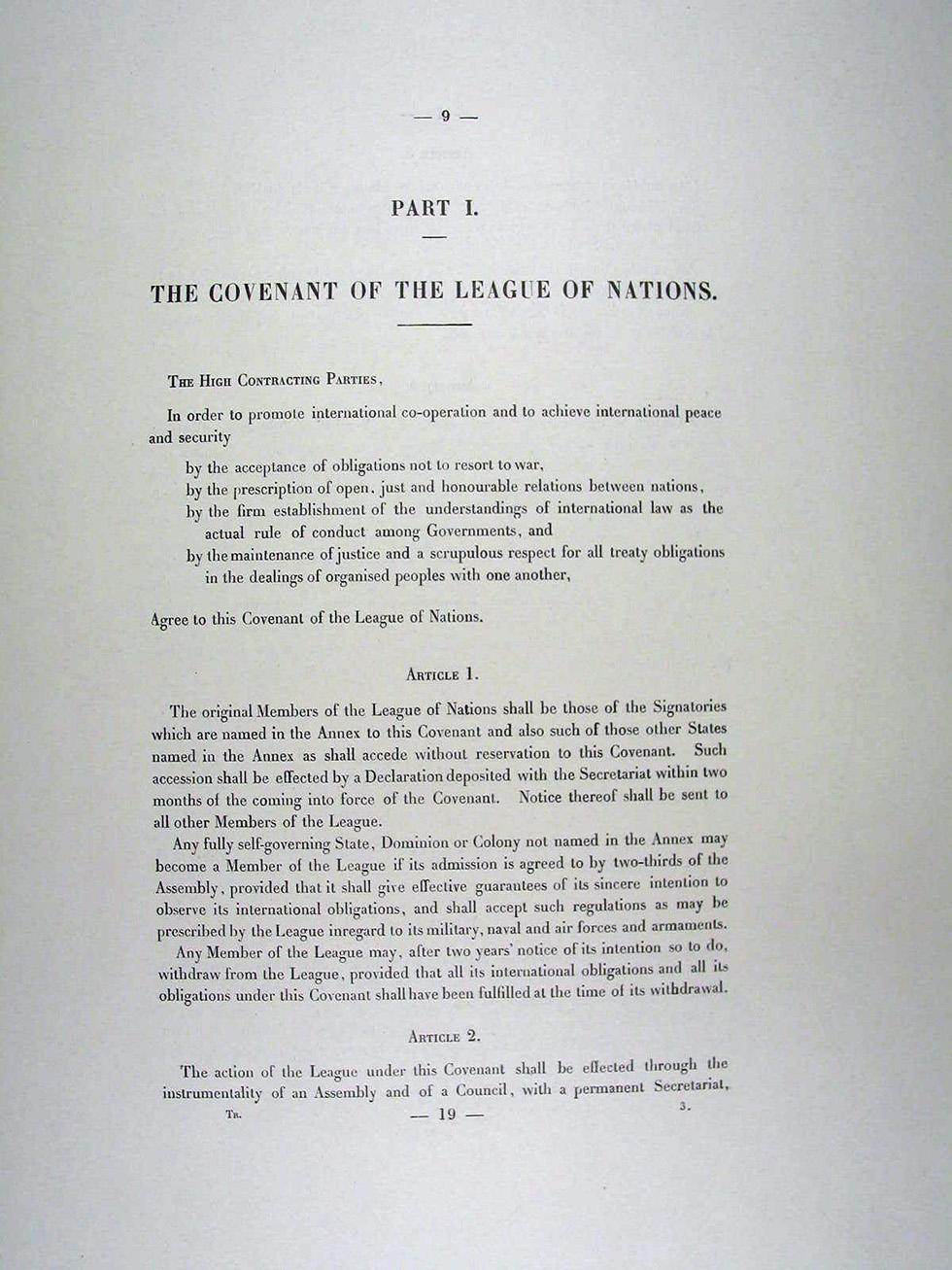

The Covenant of the League of Nations, part of the Treaty of Versailles, was an undertaking to 'promote international cooperation and to achieve international peace and security' by means of the the world's first international organisation of governments.

NAA: A11831, 6, p.224

Deposed

Returning a hero to Australia, Hughes won the election comfortably in December 1919. But the emergence of the Country Party threatened his fragile hold on power. Also, to the majority of his Nationalist Party colleagues, some of his ideas (such as allowing the Commonwealth Shipping Line to compete with private shipowners) seemed to be too close to Labor policy. The government’s joint ownership of Amalgamated Wireless and the Commonwealth Oil Refineries brought charges of socialism at a time when the Labor Party was defining its ‘socialist objective’.

In London at the Imperial Conference of 1921, Hughes argued for continuation of the Anglo-Japanese Naval Treaty and for more direct dominion consultation on British Imperial foreign policy. In December 1921, Hughes reshuffled his Cabinet, bringing in the young Stanley Melbourne Bruce as Treasurer.

With the new Country Party fielding candidates at the 1922 federal election, Hughes did not stand for Bendigo, but was pre-selected for the seat of North Sydney. After he won the seat, the family moved from Melbourne to a house in the suburb of Lindfield, in Hughes’ northern Sydney electorate.

The success of the Country Party in the Commonwealth elections of 1922 was the death knell for Hughes’s prime ministership. With the Nationalists’ numbers split in the House of Representatives, Country Party leader Earle Page refused to serve in a coalition ministry with Hughes. Hughes was forced to resign as Prime Minister and his protégé SM Bruce replaced him on 9 February 1923.

Sources

- Edwards, PG, Prime Ministers and Diplomats: The Making of Australian Foreign Policy 1901–1949, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1983.

- Fitzhardinge, LF, The Little Digger 1914–1952, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1979.

- Horne, Donald, In Search of Billy Hughes, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1979.

- Hudson, WJ, Billy Hughes in Paris: The Birth of Australian Diplomacy, Nelson, Melbourne, 1978.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- Imperial War Conference and Imperial War Cabinet, 1918–19, NAA: A981, IMP 104

- Personal Papers of Sir Joseph Cook, 1919, NAA: M3612, 13

- Treaty of Peace with Germany signed by the Principal Allied and Associated Powers on the one part and Germany on the other part, 28 June 1919, NAA: A11831, 6