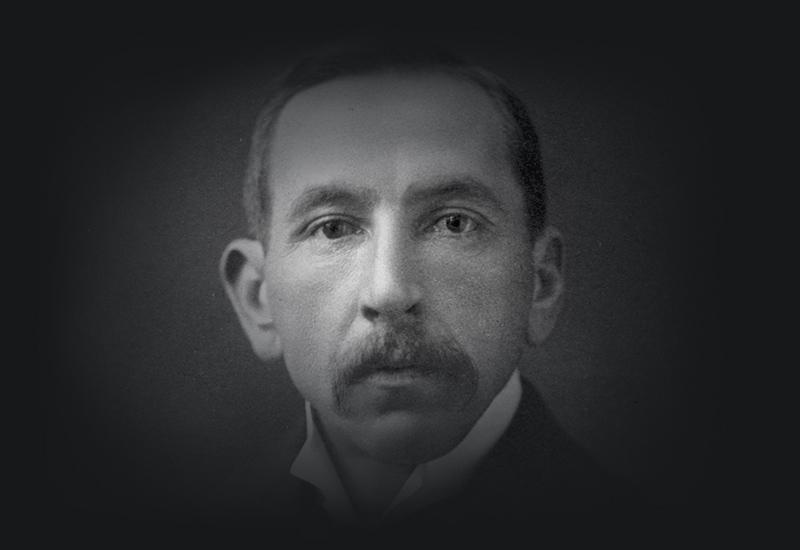

In 1901, William Morris Hughes won a seat in the first Commonwealth parliament and was Minister for External Affairs in the Labor government of Chris Watson in 1904. He was Attorney-General in the three Labor governments of Andrew Fisher (1908–09, 1910–13 and 1914–15).

As Attorney-General, William Hughes received numerous representations such as this one asking for clarification of Australia's wartime import-export prohibitions. NAA: CP359/1, 8, p. 315

Before his election to federal parliament, Hughes had joined the labour organisations that became the New South Wales Labor Party and, in 1894, won a seat in the New South Wales parliament. Hughes was 22 when he migrated to Australia from England, where he had worked as a teacher. His first 2 years in Australia were spent in Queensland where he took various jobs in the bush. He moved to Sydney and later to Melbourne. Studying part-time, Hughes gained a law degree and became a barrister.

To Australia

Hughes was born in London on 25 September 1862, the only child of Jane (Morris) and William Hughes. His background was solidly Welsh. Both his parents were from Wales, and his father, a carpenter, spoke Welsh. When his mother died, the 6-year-old child was sent to Llandudno, where he attended school. In 1874, he returned to London as a pupil-teacher at St Stephen’s School, Westminster, and became an assistant teacher there in 1879. As a teenager, Hughes joined a volunteer battalion of the Royal Fusiliers.

Hughes migrated to Queensland in 1884, aged 22. For the next 2 years he worked in the bush before arriving in Sydney as a galley-hand on a coastal steamer. He boarded in Moore Park, where he and his landlady’s daughter, Elizabeth Cutts, began a de facto marriage. Their daughter Ethel, the first of the couple’s 6 children, was born in 1889. In 1890, the family moved to Balmain and lived in a weatherboard building in Beattie Street in this waterfront suburb of wharves and working class cottages. In 1891, they opened a mixed shop in their house. Hughes did odd jobs, including umbrella-mending, and Elizabeth Cutts took in washing.

Hughes was an early member of the colony’s Australian Socialist League. After the failure of the maritime strike in 1890, he was a regular speaker at the League’s Sunday evening lectures. The Hughes’ shop stocked books and pamphlets and became a gathering place for young reformers, including William Holman. It was one of the centres for the debates and discussions that led to the formation of the Labour Electoral League in 1891 and the Socialist League in 1892.

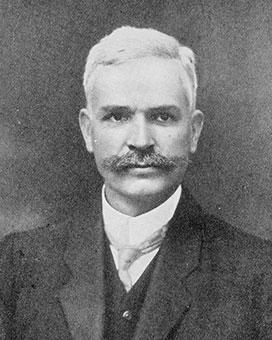

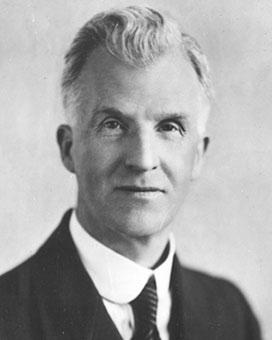

Hughes was a founding member of both leagues as were 2 other future Prime Ministers, Joseph Cook and Chris Watson. Hughes was convivial and persuasive, his ‘gift of the gab’, lively mind and fund of rollicking stories ensured he was known in a widening circle. He preferred to be known as ‘Will’ and disliked being called ‘Billy’. His intelligence was sharp, he read widely in English literature and history, and had a caustic turn of phrase.

During this period, Hughes became enthusiastic about the ideas of Henry George, whose social reform theories centred on a single tax on the unimproved rental value of all land. Street-corner speakers expounded George’s ideas, and Hughes was the Balmain Single-Tax League’s star performer. Though an advocate of democracy, he opposed womanhood suffrage, arguing that women were more conservative than men.

In 1894, Hughes worked in outback New South Wales as an organiser for the Amalgamated Shearers Union. Elizabeth Cutts managed the Balmain shop and raised their 2 infant daughters. Their son had died in 1892, a year after his birth.

New South Wales parliamentarian 1894–1901

Hughes was a candidate in the New South Wales election at the end of 1894, and narrowly won the waterfront seat of Lang for the emerging Labor Party. He retained it until Federation in 1901. In 1899 he organised Sydney’s wharf labourers and remained their union secretary for the next 17 years. He founded the Waterside Workers Federation and was elected its president, and at the same time was involved in the Trolley, Draymen and Carters Union and was its president. A moderate unionist, he preferred negotiation to industrial action.

For Hughes, the New South Wales parliament, renowned as a ‘bear-pit’ for its rowdiness, was the right place to hone skills as an abrasive orator and parliamentary tactician. Though a believer in free trade, he was instrumental in the downfall of Free Trade Premier George Reid in 1899. Like Reid, Hughes was sceptical about the proposed Australian Constitution and thought it too conservative. Hughes was thus an opponent of Federation and of its leading advocate, New South Wales parliamentarian Edmund Barton.

Federal parliamentarian 1901

Hughes nevertheless stood for the first federal election in March 1901 and won the seat of West Sydney, which included his former Lang electorate. As early as the first parliament, he urged compulsory military service for national defence and argued for an Australian naval force.

From 1901, Hughes lived mostly in Melbourne, where parliament sat and where the new Commonwealth government departments were established. His family remained in Sydney, where Elizabeth Cutts ran the bookstore and cared for their 5 children, aged from 2 to 10 years.

Hughes had studied law part-time for years, and was admitted to the bar in 1903. The family then moved to Gore Hill, across the bridgeless Sydney Harbour from their Balmain neighbourhood. When the first federal Labor ministry was formed in April 1904 under Chris Watson, Hughes became Minister for External Affairs. Although the Watson government lasted only 4 months, this was an important experience of Cabinet office.

Elizabeth Cutts died from the heart disease she had suffered for some years on 1 September 1906. Hughes remained in Melbourne and his 17-year-old daughter Ethel raised the children in Sydney. The following year, as an Australian delegate to a shipping conference, Hughes made his first trip back to England since he had emigrated 23 years before.

Deputy Labor leader 1907–15

In October 1907, the Labor Caucus elected Hughes deputy leader when Chris Watson resigned the leadership of the federal parliamentary party. When the Deakin government fell in November 1908 and Andrew Fisher was sworn in as prime minister, Hughes became his attorney-general. The Fisher government fell the following year when Alfred Deakin joined forces with former Free Trade opponents to form his ‘Fusion’ government. Hughes’ talent for invective was on display when he said of Deakin:

What a career his has been! In his hands, at various times, have rested the banners of every party in the country. He has proclaimed them all, he has held them all, he has betrayed them all ...

Hughes cut a distinctive figure in parliament. He was short in stature but had a large head, a deeply lined face and a drooping moustache. He had a restless nervous energy, hypochondria, a near obsession with physical fitness, and his hearing became progressively impaired. His first biographer described his voice as ‘penetrating, raucous and grating’, but it was an effective instrument in the days before microphones. Hughes was also a lively and engaging writer. From 1907 to 1911, he wrote a weekly column for the Sydney Daily Telegraph, under the heading ‘The Case for Labor’. In 1909 Hughes’ law career reached an important threshold when he ‘took silk’ and became a King’s Counsel.

Hughes became attorney-general for a second time after Labor’s landslide victory at the election on 13 April 1910. During its 3 years in office, the Fisher government tried to widen the federal government’s powers through two referendums. When the April 1911 referendum failed, Hughes sought to illustrate the problem by taking on the Coal Vend, a cartel of coalmine owners and shippers. Though Hughes lost the case, he gained enough ground to justify a second referendum. Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia approved the extension of Commonwealth power, but the proposal was lost overall.

During this period, Hughes had little to do with his children in Sydney, now in their teens, and still cared for by their eldest sister. In June 1911, he had married Mary Campbell and set up home in Melbourne. While Hughes was arguing the Coal Vend case before the High Court in Sydney in 1912, his teenage children were in Melbourne visiting their new stepmother at Hughes’ new home.

In the 1913 federal election, Labor lost office to the ‘Deakinite’ Liberal Party, led by Joseph Cook after Alfred Deakin’s retirement that year. 12 months later, the Prime Minister called for, and was granted, the first double dissolution of the Commonwealth parliament.

With the outbreak of World War I on 4 August 1914, Hughes argued that Labor should postpone the election by offering a political truce to Prime Minister Joseph Cook, but Caucus was not convinced. Then, at the election on 5 September 1914, a Labor government was returned.

Andrew Fisher became prime minister for the third time, and Hughes was again deputy prime minister and attorney-general. Hughes had charge of the legislation that put the country on a war footing, and he drafted and enforced the regulations under the War Precautions Act. From the beginning, he was a central figure of the government’s wartime administration.

Hughes spent much time re-organising the metals, wheat and sugar industries. Before the war, German companies had controlled the market in lead, copper and zinc. All were crucial in munitions manufacture. Hughes was determined to end this monopoly and, with the active support of businessman William Robinson, largely succeeded. In the case of wheat, ‘by the end of 1915 the Commonwealth had, in effect, made itself responsible for the entire handling and shipping’ of the crop. A similar arrangement was worked out for sugar.

Andrew Fisher increasingly delegated authority to his eager, active deputy leader. For 2 months in mid-1915 Hughes acted as prime minister while Fisher was in New Zealand. Fisher’s energies were flagging and in October 1915, with some pressure from his colleagues, he retired to succeed George Reid as Australia’s High Commissioner in London.

On 26 October 1915, Hughes was unanimously chosen by Caucus as the new Labor leader, and the following day became prime minister.

Sources

- Bolton, Geoffrey, ‘William Morris Hughes’, in Michelle Grattan (ed.), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland Press, Sydney, 2001.

- Fitzhardinge, LF, That Fiery Particle 1862–1914, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1964.

- McMullin, Ross, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party, 1891–1991, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1991.

- Souter, Gavin, Acts of Parliament, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988.

From the National Archives of Australia collection

- An Australian Navy – Hughes on the Origin of the Idea, 1903, NAA: A5954/69, 1206/4

- Personal Papers of Prime Minister Hughes, Miscellaneous, 1894–1915, NAA: CP359/1, 8

- Findings of the Full Court [Coal and Shipping Vend case]: Attorney-General’s Department, 1910, NAA: A432, 1929/2755 Attachment 3