About this record

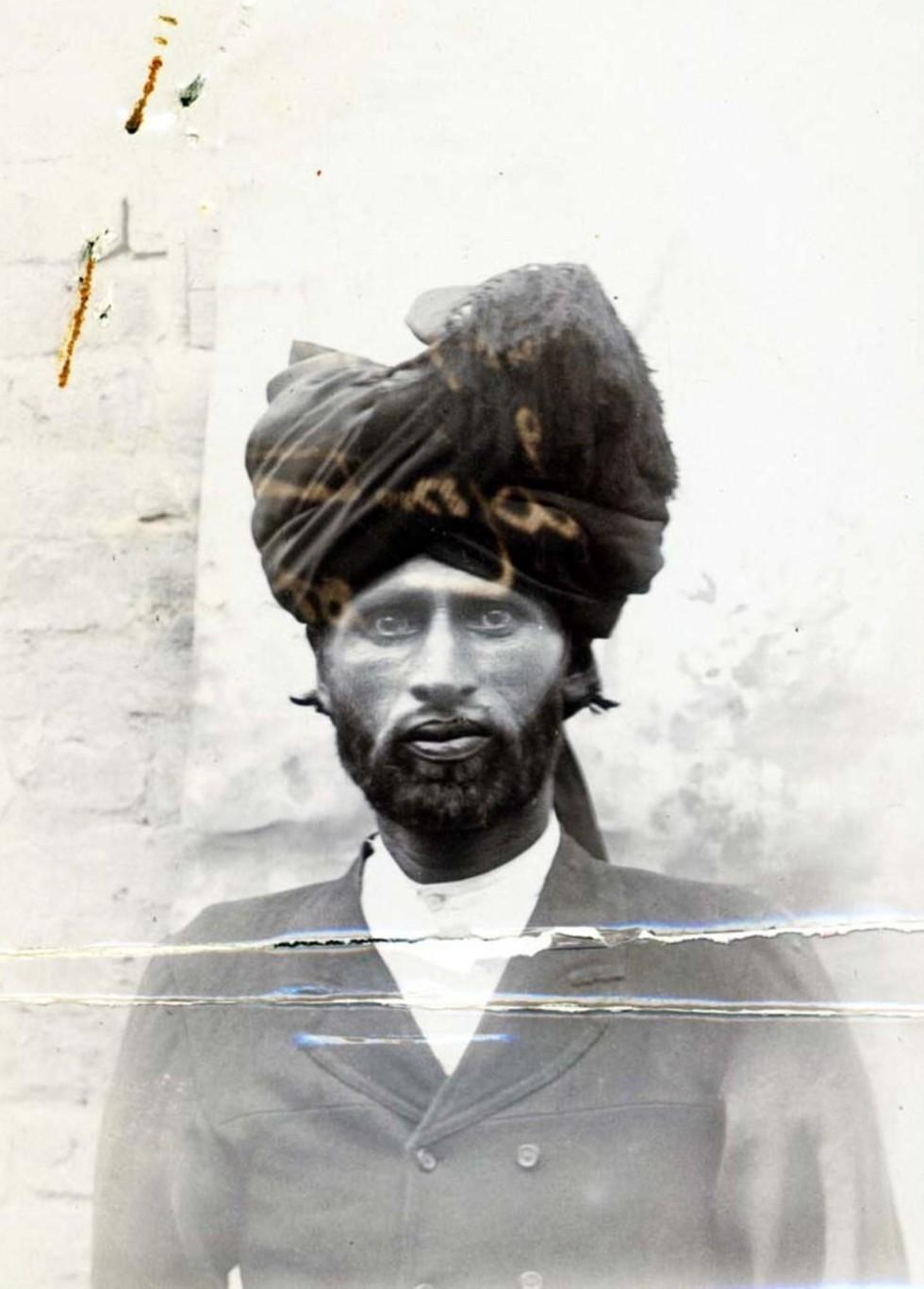

This photograph is a black-and-white formal portrait of Ellum Deen, taken in India in 1913. The head-and-shoulders portrait shows him looking straight at the camera. He is bearded and wearing a turban tied in the Punjabi style, a white Indian shirt with high-buttoned collar and a double-breasted jacket. Part of a wall can be seen in the background. The photograph has two creases across the centre.

Educational value

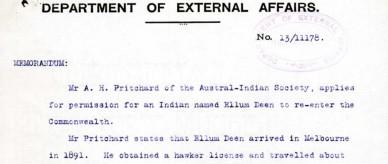

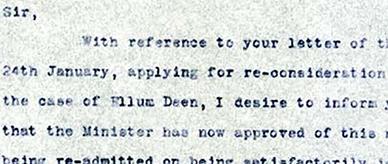

- Under the White Australia Policy, Deen had been excluded from Australia since 1907. This photograph was one of a series of documents that he used to successfully argue his case to be allowed to re-enter Australia. Deen sent letters and gathered documentary evidence for his application for the certificate that would enable his re-entry. These included identity photographs such as this one, proof of good character and proof of residence in Australia for at least five years. He was officially allowed to return in 1914.

- The photograph clearly shows Deen's 'non-white' racial origins. On seeing him at any point of entry to Australia, Customs officers would most likely have required Deen to sit the dictation test that was used to prevent non-whites from entering. The 50-word dictation test could be given in any European language chosen by the immigration official. Officials could deliberately choose a language they believed the applicant would not know, making it virtually impossible to pass.

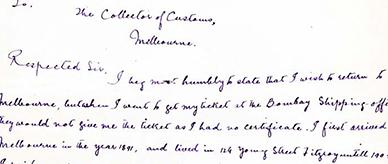

- Deen had not obtained a Certificate of Exemption from Dictation Test before he left Australia, perhaps believing that his status as a British subject would allow his re-entry. Many in Deen's position were unable to read and write English well and he may not have understood the changes made in 1905 to the Immigration Restriction Act. The Act did not explicitly ban non-whites from Australia but used the dictation test to exclude them. Shipping companies would not give passage to non-whites unless they had a certificate.

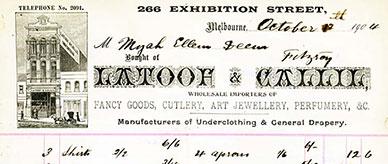

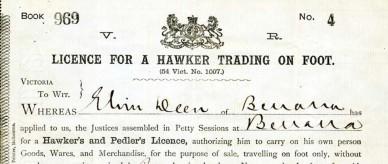

- Deen, who was from India's Punjab region (as his style of turban indicates), wished to resume his trade as a hawker in Australia, a career that many of his countrymen pursued in the late 19th century and into the 1930s. On arrival, with assistance from other Indian hawkers, these men would buy a hawker's licence and obtain goods on credit from warehouses. Travelling on foot or by horse and buggy they sold a wide range of goods—from clothes and razors to scent and safety pins—to people living in remote and rural communities.

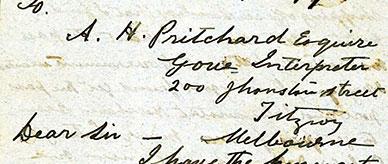

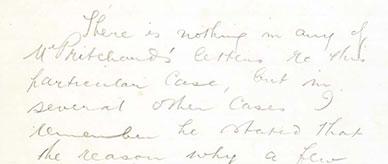

- Indian hawkers such as Deen had been allowed into Australia prior to Federation because the British Colonial Office was unwilling to enforce the anti-Asian immigration policy that Australian public opinion demanded. This openness was reversed at Federation: by the time Deen first attempted to re-enter Australia in 1907 the government's attitude had become intransigent. An English friend, the secretary of the Austral-Indian Association, did not consider it worth passing on much of Deen’s correspondence, regarding his application as pointless.

- Ellum Deen was one of many men from the Indian subcontinent who lived in Australia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, working as labourers, hawkers, camel handlers and, later, small shopkeepers and successful businessmen.

- It has been estimated that as many as 7,637 of these men were living in Australia in the first decade of the 20th century. Many worked in Australia temporarily, striving to improve the circumstances of family members back home. A significant number chose to settle in Australia.

Acknowledgments

Learning resource text © Education Services Australia Limited and the National Archives of Australia 2010.

Related records

Related themes

Need help with your research?

Learn how to interpret primary sources, use our collection and more.